Guests

by Adelle Waldman, July 19, 2013 9:34 AM

I finished my novel in the fall of 2010 — at least, I wrote through to the end of the story and even wrote those magical words, "The End." Then I waited a few months before I sent it to agents. I wanted to get feedback from a few friends, but I also wanted to cool off so I could evaluate the novel myself. I learned with my first novel that it is entirely possible for me to write something and not see what is wrong with it. Before that, I thought I was fairly self-critical, a pretty good judge of my own writing. But what I realized is that the flush of happiness that often follows in the wake of finishing a big piece of writing is a wonderful high, but it can also be blinding. And when you are in that state and you try to read your own work, you read not only your words as they appear on the page but your words suffused with your own emotion, with all these associations and colors that you bring to it. In my experience, you need — at least I need — a much cooler head to really see the thing: to see only the words on the page. And only then can you begin to wrestle with what you have. So for a few months, I wrote book reviews. I tutored. I cooked. I read a lot. I sent the novel to some friends and awaited their reactions. I tried not to think obsessively about my novel and what would happen when I sent it to agents. I obsessed anyway. I finished the novel at the end of October, but I didn't send it to agents until March. I signed with one several weeks later. I thought that was pretty much it. I imagined my agent would send it to publishers shortly after. She and I had talked about some revisions, but I was so enthusiastic, so willing to work hard and fast, that I assumed I could whip those out in a few weeks. It took a year. That year was the best thing that ever happened to me. I will never stop being grateful to my agent for it, for the year I didn't know I needed. Even if no one ever saw the novel but me, even if it never sold and lived only in a drawer in my desk, next to my first one, I'd always know that I had a much better novel at the end of that year than I'd had beforehand. The plot didn't change — and remarkably almost all the scenes that I wrote during my six-week manic phase remain in place, albeit in highly edited format and with some new material added in the interstices. Yet the novel was a different novel afterward than it was before. A lot of different things went on that year. I went through the novel from the perspective of each of the side characters. I tried to flesh each of them out, to be as fair to them as possible, to think about what they would say or do knowing that in their minds they had to see themselves as protagonists of their own lives, not side characters in someone else's stories. I also began to see more and more places where I felt like I was trying too hard with the writing, trying to prove my cleverness, sacrificing the integrity of the character's voice in my effort to assert something about me, Adelle. I expanded a section that I'd come to think was compressed and eliminated bits that I was attached to for one reason or another but were thematically repetitive. Some of the changes I made were suggested by my agent, but most were not, not directly. She's a terrific reader and great at pointing to sections that weren't working that well, noting where the writing could be tighter. But a lot of what I'm talking about couldn't have come from anyone but me. I just had to be with the thing for a year. What she did was hold me to a high standard, push me to make it better — not give me a step-by-step guide as to how to accomplish that. I don't think anyone can really do that for anyone else. A novel is too personal, too much one's own. My life that year consisted of… tutoring, and day after day of sitting at the computer, of countless nights pacing around my apartment, of frustrated tears and funks when I'd finally isolated something that could be better — and had no idea how to fix it. It was the year when I came to appreciate marathon reading — I mean, reading and rereading the thing again and again and again, reaching to the point where I never wanted to hear the names Nate and Hannah ever again and then forcing myself to keep going, read it one more time. Here's a box of drafts that I marked up (keep in mind this is one box of several, and that for every marked-up draft I kept, there are more that I threw away): I will never be able to say to people who don't like the book — at least not with any shred of honesty — "Oh, well, it's just something I dashed off!" But I don't regret a second of it. Writing this was by far the most intense and thrilling intellectual experiences of my life. I once thought getting published was the point of writing a novel. And it is certainly important, financially and in terms of feeling justified in the eyes of the world — I don't want to be Pollyanna-ish about it — but on a deeper level, I do think the best part of writing a novel is writing the novel. That's reason enough to do it. Not that the other stuff doesn't matter. Not that I don't care about whether people read the book. If you are reading this, and if you read the book, I certainly hope you like it. Read Parts One, Two, Three, and Four of "A Trip to Portland; or, The Long and Convoluted Story of How My Novel Came to Be" by Adelle

|

Guests

by Adelle Waldman, July 18, 2013 10:00 AM

When my husband and I finally got back to New York after our trip, I knew I'd have to reopen my novel and face the same set of problems that had been making me crazy when I left. To refresh: I was about halfway through the novel, and I was trying to figure out how to show a slow change in the relationship between my main character and the woman he was dating. (I should clarify I knew from when I first started the novel how its plot would play out overall — the arc of it — but I didn't know what specific set of scenes was going to take me there.) My last attempt was to write a chapter in which I had made the woman character confront my protagonist while the two of them were out for dinner. She wanted to define their relationship. But when I reread it, the scene seemed "talky." Issues were being introduced in dialog instead of being dramatized. It seemed inartful, kind of flimsy and not very effective. There were a few lines I liked here and there, but I knew by the time I got back from the honeymoon that I had to throw out the bulk of the chapter and try again, with a whole different approach. Not that I had any great ideas. I remember being very glad of a full day, in mid-September, to work on the novel — a day with no tutoring appointments. I think it was a Wednesday. I sat down to work in my pajamas in the morning. I'm not sure if I'd gotten dressed by eleven that night. It wasn't that the writing just flowed and flowed. It was more like I knew that this uninterrupted day was the best shot I had for a while in getting real work done, so I'd better use it for all it was worth. By that point, things were beginning to feel dire. I was afraid I was permanently stuck, that I'd have to give up on this novel. That day I played and played with what I had, rearranging the bits and pieces I liked from previous attempts to write the chapter. Instead of a scene at a restaurant, centered on a conversation between the two main characters, I decided to allow myself to write it as a long internal monolog from Nate, which on the one hand seemed less-than-artful — but I hoped if I got what he was feeling precisely right, I could then think better about how to present it more effectively. It worked. By the time I went to bed that night I had the bones of a structure for the chapter, and in the next few days I fleshed it out. Something else happened as well. All these ideas seemed almost as if they had been unlocked. They started to flow. I was hearing bits of dialog. Suddenly, the scenes needed to take me from approximately a point halfway through the novel to a point 90 percent of the way through began flashing through my mind in bursts. My head felt like the inside of a popcorn popper, and the pops were coming fast and furious. A period of hyperproductivity ensued. Perhaps this was a mild form of mania, I don't know. I know I was a little irritable and resentful whenever I had to do anything but work on my novel. Standing in front of students' apartment buildings, I'd scrawl notes for bits of dialog in the margins of my SAT book before sighing loudly as I headed upstairs. I didn't sleep particularly well — I felt wired most of the time — and when I finally had to stop writing, when it was time for my husband and me to, say, go to a friend's house for dinner, I'd need a drink (or two) to calm my mind — otherwise I'd just be fixated on the book and the characters the whole time. On the other hand, within six weeks I finished the first draft of the novel. Keep in mind that it had taken me two years to write the first half. It was unbelievable. And other than the fact that I'd felt a bit keyed up for those weeks, nothing terrible had happened. I continued to tutor, no matter how annoyed I felt privately about having to tear myself from my book. I didn't become an alcoholic. I didn't alienate my new husband. I just finished the novel. Of course, I would wind up spending another few months revising the book before I sent it to agents, and there would be more revisions after that — but that is a story for tomorrow...

Read Parts One, Two, Three, and Five of "A Trip to Portland; or, The Long and Convoluted Story of How My Novel Came to Be" by Adelle

|

Guests

by Adelle Waldman, July 17, 2013 10:00 AM

After our wedding, my husband and I set out on our honeymoon — a month of driving across the country. To say that we had a great time on our cross-country trip is an understatement. To spend so much time together, away from cell phone reception and email, talking for hours and hours as we drove through some of the most beautiful and overwhelming landscapes either of us had ever seen, was simply amazing — especially for a bookish pair of New York City residents driving a borrowed car, my mother's Subaru. We enjoyed the spaces between official sights as much as, if not more than, the sights themselves. I don't think either of us will ever forget our long drive through a so-called National Grassland called Thunder Basin, in Wyoming, near the South Dakota border. The designation "National Grassland" is more than a little bit misleading since tucked within the vast expanse sits the country's second-most productive coal mine, a mind-bogglingly huge surface-mining operation that supplies eight percent of the nation's coal. It kind of makes you wonder what level of industry would have to be in place before the federal government would call something "industrial land." But we wanted to see the country, and that's what we did. We visited depressed industrial towns, thriving agricultural ones, university and resort towns, and towns that were nearly abandoned, as well as one actual ghost town, near Philipsburg, Montana. We stopped for a drink in a town that was, literally, for sale for just over a million dollars (town may be stretching it, as the place consisted of only a general store, with a post-office stall, and a bar-restaurant). We camped sometimes and we stayed some nights in dingy motels. Here's a picture of our campsite in Moab, Utah:  When we got to Portland, we splurged on a hip motel/hotel called The Jupiter — after weeks of driving through rural areas, we wanted to soak in Portland's urban-ness. We were also pleasantly surprised to find that we could stay at a hotel full of fashionably dressed people, in what seemed to be a central location — and also be located only two blocks from a garage where we could drop off our Subaru for a much-needed tune-up. Am I correct in concluding that Subarus, and thus Subaru repair shops, are very popular in Portland? After we dropped off our car, we got a drink at the hotel's Doug Fir Lounge (which was kind of a fun play on the type of old-school lodge we'd stayed at in the Black Hills of South Dakota). We walked across the bridge for dinner at an Asian fusion restaurant and then met a couple writer friends for drinks at Noble Rot. In the morning, we went for a run along the river and then ate waffles from a food truck. We picked up the Subaru from the garage and drove to Powell's, where we loaded up with books for the ride home. (I'd forgotten my copy of Ruth by Elizabeth Gaskell at a motel in Nebraska and was especially glad to find another copy.) We drove up to Pittock Mansion and looked out at the city. Then we kept on driving west. Our 18-hour visit had been terrific, but we needed to make time. We headed to the coast, where we'd make a left turn and drive south for a while. Here's a pic from that day: A few days later, we had to make another left turn, a sad one. The turn off Highway One, the turn east, back. It was time to return to New York, to our lives. We'd lingered too long. We'd splurged on too many hotels, too many meals. We'd ran through our honeymoon budget. We were also behind schedule. I had to make it back to New York in time for the beginning of the academic year. My students were waiting for me. So was my novel. Read Parts One, Two, Four, and Five of "A Trip to Portland; or, The Long and Convoluted Story of How My Novel Came to Be" by Adelle

|

Guests

by Adelle Waldman, July 16, 2013 10:00 AM

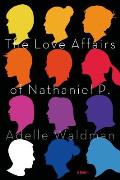

When my first novel didn't sell, I fell into a slow-burning sort of depression. It lasted for the better part of a year and began to fade only when I started to make some positive changes. For one, I moved, from Manhattan to Brooklyn. I had stayed in Manhattan for too long because I had gotten a pretty good deal on a rent-stabilized apartment near Columbia, where I'd gone to journalism school. But, over the years, most of my friends had moved to Brooklyn. I was a lone holdout, and it wasn't as if I particularly loved my neighborhood anyway. I mustered the energy to do some apartment searching, and I found an apartment in Brooklyn — a sixth-floor walk-up, but it had a great roof deck. More importantly, I wasn't so isolated from my friends. I had started working as an SAT tutor, but around the time that I moved to Brooklyn, I also began pitching freelance articles, something I'd resisted when I'd first returned to New York after writing my novel. At that point, so much of my inner life was wrapped up in the novel that I didn't think I had the psychological resources to hustle as a freelance writer, to deal with more rejections. I began to tutor as a way to make money that was wholly separate from writing. But I got over that finally, and I began writing book reviews, which was fun for me. In my previous life as a journalist, I had written about business for the Wall Street Journal and other publications. Now that I was also tutoring, I could afford to do less lucrative assignments (book reviews, at least at the level I was doing them, are comically unlucrative). I also met the man who would become my husband. He was a friend of a friend, and he showed up at my housewarming party, on the roof deck. I still felt sad and angry whenever I thought about the novel that hadn't sold. I was bitter, too. I wondered if my lack of connections in the book publishing industry had been the problem. I guess I wondered that a lot. Out loud. Because, finally, about a year after I moved to Brooklyn, my boyfriend told me that I needed to stop going on and on about the novel that didn't sell. It was time to start another. He was right. Soon after, I began working on The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. While the first novel had come easily — I wrote it in a few months — this one was much slower going. For one thing, I wasn't living in my old bedroom at my parents' house and writing full-time while eating my mom's meals. I was back in New York, working as a tutor and teaching a class on nonfiction writing. I was also writing freelance book reviews for publications like the New Republic, the New York Times Book Review and the New Yorker's Briefly Noted column. I was busy — I had, it seemed, six different jobs, none of which was quite the one I wanted and all of which were very demanding. From September to June of that year, I managed to write only three chapters. In the summer, my teaching load was lighter, and I managed another two. In the fall, my boyfriend and I got engaged. I was initially wary of having a wedding — I favored the idea of going to city hall — but, in the end, we decided to get married in the backyard of his family's house in Maine. A backyard wedding sounded simple enough, but in fact a fair amount of planning went into it. And because my fiancé was also writing a book, and because he had a contract from a publisher and a deadline just weeks before our wedding, many of the wedding-related tasks fell to me. In the academic year before the wedding, I cut down on book reviews to make more time. I managed an important revision of the novel — but I only produced another three chapters, only two of which I felt confident about. Time was one problem. But I had another as well. Before we left for Maine, I gave my husband-to-be the most recent chapter I'd written. On the ride up from New York, he confirmed what I already knew — that the chapter didn't work. I was trying to figure out how to show a relationship that was slowly deteriorating. It wasn't obvious to me how to do this in a way that felt realistic, true to how relationships really evolve over time. The changes I wanted to depict are subtle; they are often registered in tones of voice, posture that is less attentive than it used to be. I didn't want to exaggerate or insert artificial levels of drama — there weren't going to be any dishes thrown or lovers found in bed with other people. The deterioration I wanted to convey is so muted that even the people in the relationship aren't sure whether it's real or if they are imagining it, being paranoid or neurotic. In other words, I knew what I wanted to show. But... I hadn't a clue how to do it. When we got to Maine, I put the novel out of my head. It was time to focus on choosing wine and drawing up table charts and the billion other little tasks that needed to get done. It was time, too, to focus on being happy about marrying the man I loved — and about being supported so warmly by friends and family. There would be plenty of time — the rest of my life — to get back to my stalled novel. Read Parts One, Three, Four, and Five of "A Trip to Portland; or, The Long and Convoluted Story of How My Novel Came to Be" by Adelle

|

Guests

by Adelle Waldman, July 15, 2013 10:00 AM

I love Portland. I do. But the truth is I've only been there once. For one night. Still, the occasion was special. It was my honeymoon. My husband and I drove across the country, starting from Maine. We were about two-and-a-half weeks in when we reached Portland. After a couple of nights in Montana, including the hardest hike of our lives at Glacier, we were ready to do it up in a city that felt fun and cosmopolitan — and, as people who live in Brooklyn, sort of reminiscent of home, different but also familiar. We had a terrific time. Here's a picture: But it's funny for me to think of that time now, three years later, when my novel, The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P., is about to be published. When I got married, I had already been working on the novel for two years. I was only about halfway through. I had no publisher, I had no agent, and I had not published a word of fiction in my life, aside from in my high school literary magazine.  I worked as a tutor to high school kids, mostly for the SATs but also helping with English and history assignments. I worked odd hours — weekends, school nights, and over Thanksgiving break and other long weekends, when kids are typically loaded with assignments. The kids were nice, I like writing, and I like talking about books; it was a great side job for an aspiring novelist. I worked as a tutor to high school kids, mostly for the SATs but also helping with English and history assignments. I worked odd hours — weekends, school nights, and over Thanksgiving break and other long weekends, when kids are typically loaded with assignments. The kids were nice, I like writing, and I like talking about books; it was a great side job for an aspiring novelist.

But it wasn't a career. My husband, on the other hand, had a contract from a publisher to write a nonfiction book. He'd turned in his first draft just weeks before our wedding. He was definitely a writer. But when people asked what it was I did, I didn't know what to say. I had once been a journalist, but that felt like a long time ago. My husband was a writer. I was an SAT tutor with a Microsoft Word document. And I knew all too well that a Microsoft Word document doesn't always become a novel, not in any sense and certainly not in the published sense. Several years earlier, when I was 29, I had quit a gig as a columnist for the Wall Street Journal Online to write a novel. I sublet my New York City apartment and moved in with my parents in suburban Maryland for six months to do it. Never mind that in my previous attempts to write fiction, I had never before gotten farther than 50 pages. But within five months, I'd produced something that could only be called a novel. It had a beginning, middle, and end. It was 500 pages, had a large cast of characters — it was told from the various perspectives of members of a middle-class Jewish family on the Upper West Side of Manhattan — and had a clear plot, with the arrest of one of the daughters in Peru setting off a chain of reverberations for the whole lot of them. When I finished I sent it off to agents. A bunch passed, but one said yes, and days after my 30th birthday, the agent sent the book to publishers. At first, I waited eagerly. The first rejection came, but it was so nice it scarcely registered as a rejection. After a few weeks and several more rejections, I began to grow nervous. A few months later, I knew for sure that the novel wasn't going to sell. As anyone who has ever tried and failed to publish a novel can attest, this was devastating... Read Parts Two, Three, Four, and Five of "A Trip to Portland; or, The Long and Convoluted Story of How My Novel Came to Be" by Adelle

|