It's always heartening to hear that your

book would make a great holiday gift. One, because I love the holidays to an almost frightening degree. (I live in a small New York City apartment where outside on my deck are two large bins — one for my 8-foot artificial Christmas tree, the other for my Christmas ornaments.) And two, because the giving of books has always played such a joyful part in the holiday season.

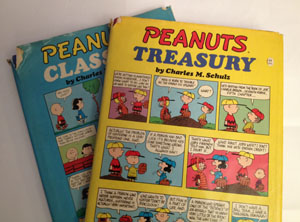

In fact, one of the greatest Christmas gifts I ever received as a kid was in 1977 when I unwrapped a set of comic books — Peanuts Classics and Peanuts Treasury — which as you can see by the photo on the left, I still have (and reference) to this day. I know the exact year of the gift because of the inscription inside from my parents.

In fact, one of the greatest Christmas gifts I ever received as a kid was in 1977 when I unwrapped a set of comic books — Peanuts Classics and Peanuts Treasury — which as you can see by the photo on the left, I still have (and reference) to this day. I know the exact year of the gift because of the inscription inside from my parents.

My only wish is that I had received these books when I was just a little younger so that the signature inside would have been from Santa instead. That way, today when friends would come by my apartment, I could open up the books and say, "Look whose autograph I got! Isn't that freaking amazing?!" Then my friends would give me that look that indicates they're trying to find the most delicate way possible to bring up the subject of psychiatric evaluation, all the while fearing I'm next going to show them a bell I believe is from Santa's reindeer harness that only I can hear (and which they can tell from my insistent clanging is clearly a cowbell).

But all this made me realize that while there are all manner of perfect books to give for the holidays of December, there is little in the way of ideal literature for the holiday just around the corner, Thanksgiving (with the possible exception of the transcript to A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving, published if only to show that a dog and a bird could indeed make a serviceable holiday meal, so long as they had ready access to a popcorn machine). That's why I was completely elated to uncover the following letter from a teenager — documenting the very first Thanksgiving — that will either prove to be one of the most significant historical finds of the last 400 years or a forgery entirely on my part. So print it out, wrap it up, and give it to your favorite person with the exclamation "Happy Thanksgiving!" Then patiently wait for your Thanksgiving present, and when you realize one is not forthcoming, let out a long, exasperated sigh and say, "Way to show the holiday spirit."

A Teenager's Written Account of the Very First Thanksgiving, November 1621

The feasting has summarily been concluded and I have repaired to my room, far from relatives most fractious and grievances oft repeated to no avail except to sway Aunt Ecclesianne to dip once more into the sherry and regale even the most unseasoned family member with what a total arse they be.

The feasting has summarily been concluded and I have repaired to my room, far from relatives most fractious and grievances oft repeated to no avail except to sway Aunt Ecclesianne to dip once more into the sherry and regale even the most unseasoned family member with what a total arse they be.

I had stepped not one manfoot into the repast quarters during the time of preparation when I was immediately struck with comments most thunderous about my unkempt head fur and demeanor quite displeasing. Our family, being all well recovered in health and having all things in quantities good and plenty, had apparently done little to close their fowl holes for even one damnable moment. Rather, they took to the occasion of my verbal lashing yet again with great practice and flourish, once more rekindling my passion for a native onslaught, a great blaze, or some warbler of alarming size to finally rid me of these blood fellows.

While I was instructed vigorously on how I was slicing most unwell the almonds for the greens, my valueless sister arrived, short in wanting to assist in our cooking endeavors but long in bodily attributes canine. Rather, she took the moment to shine but on herself as was her want, introducing her new swain to relatives no doubt astounded that a woman of such unpalatable demeanor could land a man without ammunition or rock most sharp. For his part, the man I readily surmised to be no greater possessed of intellect than the nuts I angrily cleaved. Yet within but a moment, our feast had miraculously transformed into a celebration not of our great harvest but rather a fete in honor of two people who could not look less like that of God's image if their hands were cloven.

Soon the relations not so immediate arrived, complaining of foot traffic unending and sharing long tales whose points even the great native scouts could not manage to uncover. Grandfather himself directly embarked once more into his yarn of how the very idea for Martin Frobisher's expedition had been vilely stolen from him, only rather than a "Northwest Passage," Grandfather stated he would have explored for "tobacco mermaids" instead.

Meanwhile, several of the guests' arms groaned most heavily from the prepared meat they carried into our dwelling, notwithstanding my mother's pleas that she was well in capacity to prepare the feast. Said guests countered that people oft like a selection — especially more than one lone pie — and not everyone takes to the singular aridness of my mother's turkey. This put my mother in a humor most abominable, which my Aunt Benefice sought to allay by stating that this is why they really ought to have held the feast at her house instead.

I asked to be excused, fearing being confined with such persons would soon make me disembowel my feces and utter remarks untoward yet unerring, but even such a simple request was furiously denied. Alas, I was harshly instructed to set the manner of the table alone while all manguests sat before the large fireplace, preparing for an afternoon of watching whose pinecone would blaze in great, colorful glory.

After what seemed to this author an interminable era wherein I tried to make myself scarce whenever chance allowed — only to be utilized repeatedly as the beast of burden unassisted — the food was brought forth to the banquet surface. I had not one hand on a ladle of potatoes mashed when I was scolded for impertinence and told by my mother to proffer thanks. "For what?" came fast my reply, only to receive a slap wholly sharp on the posterior of my head. Knowing that I had no choice in the endeavor and seeing this as my only moment to speak most freely, I chose to educate my family most disagreeable on the atrocities they had brought upon not only the initial inhabitants of this land but on this very person.

"Oh Lord," I commenced with great solemnity, giving not a soupçon of what was to come, "We thank you for allowing us to defile your earth with contemptible persons who want only for themselves and care not for their fellow man or creature. We thank you for the ammunition with which to blow asunder more animal than Noah himself could board, even if he dismantled and stored them in containers non-perishing for later utilization. We thank you for the arrival of my sister and her manfriend, whose very countenances surely make His Lord question His own powers. We thank you for the wisdom of our parental folk, who sought to keep me from enjoying but a seventh a fortnight skiing with peers on Plymouth Inclines, rather imprisoning me here to toil at their unkind will while the most contemptible lot of individuals ever gathered not before a barrister or executioner gorged themselves on appetizers and imbibed great quaffs of ale as if the end were near and you, Lord, would only welcome the plumpest, most pickled, most execrable vermin to enter thy kingdom. Amen."

Sadly, I was not six words into my oration when great cries and several blood pressures rose from the table, seeking to shout me down only to be met with great failure. Great paternal Uncle Cotton was first to damn my good name, swearing that my absence of piety was no doubt grave indication of my maternal side's deficient breeding. My mother's father Cotton was swift to take umbrage at this assertion, declaring that Uncle Cotton could take nourishment from his manmember for as long as he sought to suppose such twaddle. That was when my Aunt Cotton, for reasons still unknown, thought it best to bring up the curious displacement of departed Great Grandmother Cotton's china most fine, mere days before the reading of her will. My mother, locating great offense in this, took the occasion to mention to the gathered that Aunt Cotton's daughter Impudence had been seen "plowing the field" with the Reverend Increase's niece not two days ago. Said daughter, turning crimson as the harvest beet, then summarily countered that her brother Barrett had most recently acquired a stamp of ink fully permanent on his reaping arm, fashioned in the visage of a skull immolated. My detestable sister then wailed fiercely that everyone was churning gray clouds on what she took to be her special day, and hers alone, whereupon I with tremendous skill hurled an acorn squash at her proboscis. Soon all family took to flinging pies at one another with violent force. And it was at that very moment, when the dining-hall sky was thick with mincemeat and butternut, that my Aunt Ecclesianne stood up, swigged from the sherry bottle she no doubt stored most secretly in her garments, and bellowed, "A pox on you all!'" It was then that we learned she had the devil's pneumonia and soon, alas, we would as well.

I pray this be the last time we visit this holiday.