When science was first invented, its creators saw it work hand in hand with art and literature to seek out the deep truths of the world. What went wrong?

Joseph Banks, founder of the Royal Society, and Humphry Davy, prominent among the first professional chemists, were good friends with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Wordsworth, and Mary Shelley. While Banks and Davy were creating the idea of science as a professional occupation, these poets and authors were busy incorporating the latest scientific discoveries into their works. Shelley's Frankenstein was the first science fiction novel, simply because Shelley was the first author who had a scientist to consult with.

Both sides of this collaboration saw the other as vital to their efforts. The poets needed scientists to enlighten them with new truths (new ideas having been in desperately short supply since the Greeks said pretty much everything there is to say about the world and human nature without the aid of science). The scientists, in turn, needed poets to make connections between their work and broader humanity, to warn them against an overly mechanical interpretation of the world, and to spread the word about new discoveries to a wider audience.

Although both sniped at each other from time to time, neither side saw a fundamental conflict or split between science and the arts: Each respected the other for its contributions. How impoverished in comparison is the current situation, with scientists viewing artists as lightweights, and artists having such distain of science that the notion of a science fiction novel winning a literary award is as far-fetched as some of that genre's plot lines.

Some artists are, in fact, lightweights, poseurs, and hangers-on (but then, so are a number of scientists). But many artists are making valuable contributions, not only aesthetically, but also scientifically. Visualizations are an example: An eye for color, and willingness to put effort into presentation, have led many a scientist to a better understanding of their own work.

Some artists are, in fact, lightweights, poseurs, and hangers-on (but then, so are a number of scientists). But many artists are making valuable contributions, not only aesthetically, but also scientifically. Visualizations are an example: An eye for color, and willingness to put effort into presentation, have led many a scientist to a better understanding of their own work.

Conversely, not all science is ugly tables of numbers and dead rats. From the astonishing worlds within worlds of the Mandelbrot set, to the sublime insights into human nature offered by the Freakonomics style of on-the-street economics research, science continues to offer art and literature an endless series of surprising, marvelous, horizon-expanding ideas to work with.

Although science and art have been at odds for centuries, since beginning their divergence even during the Romantic era of Davy and Coleridge, there has always been some dialog between the two. With the widespread deployment of computer technology they are working together more closely today than in quite some time.

An artist wishing to make an animated movie in which things move naturally has no choice but to use a "physics engine," modeling software that simulates the motions of real objects. A scientist wishing to publicize her latest work on a NOVA show has no choice but to enlist the aid of a visual artist to help create dynamic animations and visualizations that interpret her results.

Perhaps nowhere are art and science more closely mingled than in the world of photography. All photographers have to come to an understanding of the physics of light. My favorite book on photographic lighting reads almost like an optics textbook (Light: Science and Magic: An Introduction to Photographic Lighting).

And nearly all scientists sooner or later end up documenting their work with some form of photography, and thus sooner or later come to the realization that there is an art to taking a good photograph, one that communicates your idea and maybe gets you on the cover of Nature.

And nearly all scientists sooner or later end up documenting their work with some form of photography, and thus sooner or later come to the realization that there is an art to taking a good photograph, one that communicates your idea and maybe gets you on the cover of Nature.

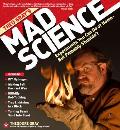

My book Mad Science, and the Popular Science magazine column on which it is based, are very much collaborations between art and science. I contribute the science, but my column and book would not be what they are without the contribution every month of the top notch commercial photographers I work with. They bring the subject to life and help communicate it to the public, just as Coleridge brought the chemical ideas of Davy to life ("... so water and flame, the diamond, the charcoal, and the mantling champagne, with its ebullient sparkles, are convoked and fraternized by the theory of the chemist") and Shelley brought Faraday's electricity literally to life with her monster. (How's that for pretentiously associating my poor efforts with the giants of history?)

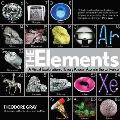

My most recent book, The Elements, owes a lot to what my co-photographer Nick Mann and I have learned from our interactions with these professional artists. It's basically a collection of fairly humdrum objects, a nodule of cobalt or blob of low-purity silicon, which have been given the same treatment that an advertising photographer gives his subject. The assignment is this: Here's a thing, make it look good! We have applied this ethos to the hundreds and hundreds of objects that appear in the book. Each one is treated like a star, with our goal being to use all the science and art of photography to make it look as attractive and interesting as possible.

In tomorrow's post, I will talk about the importance of recapturing some of the fun of how chemistry was done back in Davy's day: Raw and dangerous.

÷ ÷ ÷

From https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Faraday_Michael_Christmas_lecture.jpg:

Michael Faraday gives a Christmas Lecture at the Royal Institution. The two children in the front row center are the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Edinburgh. Painting by Alexander Blaikley.

From https://www.tate.org.uk/britain/exhibitions/gothicnightmares/rooms/room2_works.htm:

Theodore Von Holst's frontispiece to the 1831 edition of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein.

From https://periodictable.com/theelements:

Cobalt may be a useful chemical element, but it's also surprisingly elegant.