I've just written a novel in which the main character is a classical composer, by necessity a fictional one, called Charles Jessold.

Jessold finds himself — not, you understand, due to the astounding quality of my novel, but purely because he now fictionally exists — in a noble tradition of fictive composers. Alex Ross, author of the much-praised The Rest Is Noise (a study of the history of 20th Century music), has written brilliantly about the lineage of similarly non-existent composers. [You might need to become a member, but the original New Yorker article, and its sequel, are here and

here). There are deadly boring fictional composers (Jean-Christophe by Romain Rolland) and profoundly interesting ones (Mann's Adrian Leverkuhn in Doctor Faustus): all seem to follow in the footsteps of Proust's Vinteuil.

I set myself the task of trying to work out why these various composers succeeded or failed as fictional creations — sometimes they fail because they are clearly a stand-in for the Writer/Artist, an idea more than an actual composing composer; some fail because their work is not believably described. My first favourite fictional composer was Kuhn (rather than Leverkuhn), the narrator of Gertrude by Hermann Hesse, an author we perhaps read mostly when we were teenagers. I urge you to read (or re-read) Gertrude. I found it so affecting that I gave Heinrich Muoth, the singer in Gertrude who marries the love of Kuhn's life, a guest appearance (along with Adrian Leverkuhn) at the premiere of Strauss' Salome in Charles Jessold, Considered as a Murderer — also in attendance at this premiere was Adolf Hitler. Sadly, he wasn't fictional at all, though whether he actually attended the premiere is a matter of debate: he told Strauss' son he borrowed money to do so.

One of my favourite recent fictional composers is Catherine McKenna in Bernard Mac Laverty's Grace Notes: the novel tells her story in two parts, with the second part first. It's hard to imagine the structure working until you read it; then it's hard to imagine the structure improved. But my favourite of all, and I thank Mr. Ross' article for suggesting him, is Gilbert Rosenbaum from Randell Jarrell's sensational (and only) novel Pictures from an Institution. Although nothing much happens, every sentence is a dark gem. Rosenbaum is probably the novel's most likable character (his music is described in supreme detail) and his saving grace is the fact that he might, just might, be a failure. I found a nice paperback of this at Bookhaven in Philadelphia for $3 — well-priced, well-bound and it hasn't fallen apart yet. I already recycled my copy and passed it on to someone who will love it, so no photo of that. I have yet to find a reasonably priced first edition.

The book that set me off down this fictional composer path — having seen a Werner Herzog documentary about the man in question — was Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa: Musician and Murderer by Cecil Gray and Philip Heseltine, published in 1926. (Heseltine was himself a composer, working under the unlikely psuedonym of Peter Warlock.) Gesualdo himself was real, but his life seems fictional in the extreme. He murdered his wife and her lover &mdash adultery was just cause for uxoricide in those days, so he got away with it — and went on to produce some bizarre, shockingly dissonant, extremely beautiful, music very much in advance of its time. Part II of Gray and Heseltine's beautiful book also provided me with a title for my new novel, although in Charles Jessold, Considered as a Murderer I tried to tease different implications from the title.

In a world where there are fictional composers, there must therefore be fictional critics. My non-existent critic, Leslie Shepherd, narrates Charles Jessold's story. I read a Stravinsky biography that was fascinating on the subject of his relationship with musical critics, and this made me want to write a novel with this co-dependent relationship at its centre. To say more than that would not be prudent (though I will add that my composer and critic are not gay.)

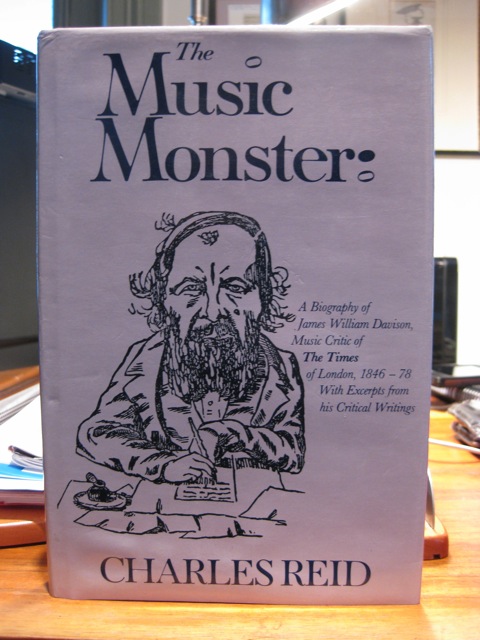

I read quite a few contemporary critics for background, while trying to keep Shepherd his own man — he is very keen on furthering the cause of English music at a time when a) Britain's favourite composers were all German and b) we were just about to go to war with Germany — and, of course believable. However, I then read The Music Monster by Charles Reid, the biography of James William Davison, a British 19th Century music critic. Once I read this shockingly good book, I realised that nothing I made up about my own critic could measure up to the hideous reality of Davison: he likened Chopin's music to that of a sickly schoolboy. Tchaikovsky's Romeo and Juliet he dismissed as "rubbishy". Verdi's Rigoletto would "flicker and flare for a night or two, then die and be forgotten." "Wagner cannot write music" was his opinion, Tannhauser was "commonplace, lumbering and awkward,' and Lohengrin "an incoherent mass of rubbish". Liszt was "talentless funghi", Berlioz "a vulgar lunatic", and Schumann's music could "hardly be called music at all."

Davison, who regularly took bribes and considered Sterndale Bennet (me neither...) the greatest composer of the day, was lead musical critic of The Times, the main newspaper in Great Britain for 32 years. No-one even had the decency to make him up, so I can't see how my logical, fussy, ideological Leslie Shepherd could fail to appear realistic. Davison might possibly have belonged in this book, the wonderful cover of which, had I not squeezed it in here, might not have made it into this blog.

If anybody is in NYC or thereabouts on February 23rd, Alex Ross and I will be at Hunter College, talking about Jessold and the lineage of Fictional Composers.