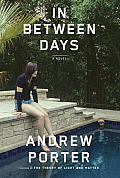

In the coming months, I'm sure I'll be asked a lot of questions about the issue of family in my work, not only because it's such a prevalent theme in my recently released novel,

In Between Days, but also because it was one of the central themes of my short-story collection,

The Theory of Light and Matter. Of course, whenever people ask me to elaborate on my interest in families — and, specifically, dysfunctional families — I can't help but feel that they're secretly expecting me to divulge some interesting detail about my own or to admit that, yes, the families in my fiction are in many ways a direct reflection of my own family. But the truth is, the family I grew up in bears little resemblance to the families in my fiction, and moreover, the characters I describe couldn't be more different from my own parents and siblings.

And yet still, the question remains: Why this preoccupation with dysfunctional families?

I guess the best way I can answer this question is by explaining that my interest in writing fiction grew out of my interest in people and the ways that people interact with each other. And I've always been especially interested in group dynamics, whether it be the dynamics of a workplace, a social situation, or a family. I think there's something very revealing about the way people interact in groups versus the way they behave on their own, and inherent in this disparity is usually some type of conflict: the public self versus the private self. The person you appear to be versus the person you really are. And I suppose that families in particular are rife with this type of conflict. After all, in a family, we all play a role, and usually that role has been ingrained in us from an early age. We're expected to do certain things, act a certain way, and accept certain responsibilities based on the expectations of those around us. And yet, at the same time, every member of a family has his or her own private life, a life filled with separate hopes, fears, desires, and insecurities, things that may have nothing at all to do with the family itself.

In writing both my short-story collection and my novel, I think I was probably most interested in exploring this type of disparity and in showing how a certain emotional distance often grows out of it. With my novel, In Between Days, for example, I made a conscious effort never to show the four members of the Harding family in the same place at the same time. I wanted to underscore the fact that even though they were all part of a unit, that unit was never entirely complete. And with my first book, I took a similar approach, consciously avoiding depictions of large group scenes, trying instead to depict the various families I wrote about as groups of separate individuals. As I was doing this, however, I wasn't thinking about any family in particular, and I certainly wasn't attempting to depict my own; I was simply looking for a way to explore the type of emotional distance that seems to exist in all families, no matter how close they may be.

In writing both my short-story collection and my novel, I think I was probably most interested in exploring this type of disparity and in showing how a certain emotional distance often grows out of it. With my novel, In Between Days, for example, I made a conscious effort never to show the four members of the Harding family in the same place at the same time. I wanted to underscore the fact that even though they were all part of a unit, that unit was never entirely complete. And with my first book, I took a similar approach, consciously avoiding depictions of large group scenes, trying instead to depict the various families I wrote about as groups of separate individuals. As I was doing this, however, I wasn't thinking about any family in particular, and I certainly wasn't attempting to depict my own; I was simply looking for a way to explore the type of emotional distance that seems to exist in all families, no matter how close they may be.

Still, in the coming months, as people begin to read In Between Days, I know that a certain number of readers are going to assume that the Harding family is my own or that the conflicts that the Hardings face are conflicts that my own family has faced, when in fact neither of these things is true. In the past, these types of misconceptions, or assumptions, used to bother me a little, but recently a friend pointed out another way of looking at it: If people who read your fiction assume it's nonfiction, she said, that's actually kind of a compliment. It means you've done your job.