It's characters who make a story come alive, who give it its narrative richness. It's characters who readers care about, who make them want to turn the page to discover what happens next. It's characters who propel the narrative forward, whose lives the readers latch on to and live with. Without complex, intriguing, and affecting characters — people as large as those we encounter in our daily lives — no one is going to care about the story that's being told.

The setting can be exotic. The history that's being shared can be both little-known and compelling. But without full-bodied characters, the story is going to feel fat, and thick, and slow. The reader just won't give a hoot.

Now, if you're writing a novel, finding the right characters for your story is simply a matter of talent. You can use your imagination to invent the full-bodied and deep-feeling creatures who will inhabit your world. Of course, this sort of God-like creation is a pretty tough business, and it sure facilitates the process if you're a genius.

However, in a nonfiction book, especially in a narrative history where the goal is to tell a page-turning story as affecting as any novel, the challenge of getting the right characters for your story is arguably no less daunting. In its no-nonsense way, it's perhaps even trickier.

You see, the characters that drive your story, who inhabit every page, must be real. They must live and love and dream and fight on the page according to the actual circumstances of their lives. You can't invent or fabricate an incident or an emotion to make a better story. So if you're going to play by the rules, you need to find some pretty intriguing real-life people.

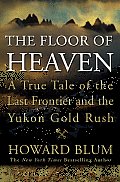

I think I found them.

First, I had Charlie Siringo. Here was a man who'd been a hard-charging and hard-living cowboy — and who then became a Pinkerton detective. To each of his cases, he brought a cowboy's resources — courage, tenacity, self-sacrifice, the self-confidence not to give in to overwhelming odds, and, oh yeah, a quick draw. He also was a man who had fallen deeply in love — only to have his young bride die literally in his arms. He lived with his share of despair. He was familiar with defeat.

Next, I had George Carmack. He was a man driven by the pipe dream of finding a fortune of gold — and yet actually did it. He struggled for years against an indomitable Nature in the frozen north, fought loneliness by joining up with an Indian tribe, and found love and companionship — only to turn his back on the people who'd helped him through his struggles when he struck it rich. His successful life was also a personal tragedy — and one, some would say, he deserved.

And finally there was Soapy Smith. He was a man of great contradictions, one moment the ruthless con man, the next a philanthropist with a remarkable generosity of spirit. He was also a visionary, a leader of men, a lover of women — and a true scoundrel.

These were the sort of full-bodied men, heroes and villains, who had helped shape this country. I greedily latched on to them, and in return they gave me my book.