The legendary University of Michigan football coach Bo Schembechler never hesitated when asked to describe his favorite play.

"Fullback up the middle," he'd say with a confident smile.

The most basic, simple hand-off was celebrated by the Wolverines in a sport that often tends to celebrate gimmicks. What made the statement all the more noteworthy was that everyone, from Ohio State to Northwestern, knew it was Schembechler's favorite.

So when he was pressed one day to explain why he continued to call the play even when opponents knew it was coming, his response was as straightforward as the play itself.

"They know it's coming and we know it's coming," he said. "Now, we'll see who's better."

Politics can be equally rough and tumble on its participants, with verbal and emotional bumps and bruises replacing physical ones.

In Colorado, since 2004, rogressives supporting Democratic candidates have run Schembechler's version of the fullback up the middle in each election. Without question, they've run it better than they did in the last election. Still, the state's Republicans have been inept at stopping it.

"The (Republicans) are befuddled in part because they're wrestling for the soul of their defense," said Colorado Gov. Bill Ritter (D). "They don't know if they want to play with conservatives or if they want to play with moderates. They don't know if they should all be linebackers or if they should all be safeties. They don't have a sense of how to defend this because they on the other side have an ideological split that keeps them from being unified and really able to make their case to Coloradans."

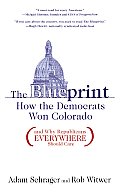

The success of Democratic candidates is thanks to the infrastructure built by progressive nonprofits and funded by significant donors, and is a blueprint being copied by other states. Simultaneously, Republicans in other parts of the country as well as in Colorado are struggling to define who they are.

"Since Ronald Reagan, there's really been a coalition in America of gun conservatives, tax conservatives, and social conservatives who have forgiven each other their trespasses," said Ritter. "Where they didn't agree, they didn't bother. They weren't bothered by their lack of agreement because what they believed in was Republican rule. And as Republican rule did not deliver on the promise to those groups the way they wanted, they began to be more suspect of (their fellow Republicans)."

The stories are numerous.

In 2004, a conservative group publicly attacked a Republican state house candidate a week and a half before the election through a vicious mailing to thousands of households in her district. It accused her of not being in favor of school vouchers and for "caving to union bosses."

In 2004, a conservative group publicly attacked a Republican state house candidate a week and a half before the election through a vicious mailing to thousands of households in her district. It accused her of not being in favor of school vouchers and for "caving to union bosses."

She would lose by 48 votes out of more than 27,000 cast.

In 2006, a Republican gubernatorial primary led to the party's eventual nominee being tarred and feathered for flip-flopping on fiscal issues. Ritter would take advantage and retake the governor's mansion for Democrats for the first time in eight years.

Other Republican candidates were attacked for wanting to take away people's guns or for their stand on abortion. Ronald Reagan's 11th Commandment, Thou shalt not attack fellow Republicans, was ignored.

"A civil war started within our party between moderates and conservatives that over time resulted in Democrats winning state legislative seats that historically had been Republican," said the state's GOP Chairman Dick Wadhams. "Several moderate Republican incumbents found themselves fending off or even being defeated by conservative challengers. Although abortion certainly dominated these primaries, gun rights and fiscal issues also figured prominently. These primaries were so viciously fought that it often drove moderates to support Democrats in the general election or found conservatives just not voting at all in a race with a moderate Republican candidate, resulting in Democratic wins."

Compared with what happened with the Democratic candidates, the contrast between parties is striking. Take Ritter for example. A pro-life Catholic, he had people telling him he couldn't win a primary. Alas, he didn't have a primary.

"That is maybe the single best indication of how Democrats in this state are at a place where they figured we as a party need to really live up to this slogan we have about being a big tent party. Republicans say that as well, but we really believe in it," said Ritter. "In Colorado, the electorate has not been as receptive to the social conservatives because there are other, bigger, more meaningful issues than what appear to be the social issues that make up the social conservatives' main agenda. You can talk a lot about gay issues, about abortion, about things like this that I don't discount as being important issues, but if your roads are crumbling, your schools are falling down around you, and you have a health care system that's entirely broken, then people in this state are going to look to leadership and say, what are you doing?"

If you ask some of Colorado's Republicans, their message to their counterparts around the country will be to watch out for large liberal donors who intend to spend their way to power. If you ask others, they'll quote the greatest member in the party's history, Abraham Lincoln: "A house divided against itself cannot stand."

Or, put a different way by the state's former senate majority leader, Norma Anderson, "Republicans have forgotten that politics is a game of addition, not subtraction."

Coming up tomorrow: why the progressives have determined the future of state legislatures to be so important.