Travel writing is a demanding genre. It requires both the toughness to make a hard journey and the sensitivity to record it. They don't often coexist. There are travelers who write, and writers who travel. Some can make crossing a suburban street fascinating; others bore you while describing a feat of exploration in the Amazon.

People say that the world is shrinking, that there is nowhere left to go. They are quite wrong. The world is never constant. Some thirty-five years ago I drove overland from London to India. It was fairly easy to do then, cruising through eastern Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Kashmir and Pakistan — a beautiful journey, and only dangerous by chance incident. But you could not do it now.

Yet in those days virtually the whole of the Soviet Union and China were inaccessible. So as the curtain rises on one part of the world, it falls on another. And every change needs travelers to witness it: not only because the world is in flux, but because the tastes of travelers change with every generation.

In a sense, we travel writers make the world our own. Objectivity disappears. Open a book by Bill Bryson or Paul Theroux, and you are inhabiting a particular author's head as well as his chosen country. That is the pleasure of it: the world seen through the eyes of another.

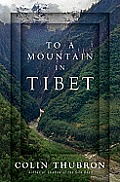

People tell me my own written world is lush and melancholy. Odd, this, to me. I don't feel very lush or melancholy. Only this last book has a sad tinge, written as it is after the death of my mother, and touched by Tibetan ideas of the afterlife. No revelation or catharsis: more a broken meditation as I climb a valley of the Ganges into Tibet.

"You think you are making a trip," wrote the Swiss writer Nicholas Bouvier, "but soon it is making you — or unmaking you."

And that is how it should be.