One of the things I discovered in writing a nonfiction book is that unlike your fictional characters, the people you meet and write about enter your life, not just your imagination. They call you up on the phone or send you holiday letters at Christmas. After all, you've written about them, given them a second life inside a book, and that's a special bond. And if you have inherited those sociable Dominican genes, which I have, you find yourself with a lot of new friends. This without even joining Facebook!

With A Wedding in Haiti, people who were not an integral part of the story became a part, however briefly, of our lives. Two who led me on a little side journey with a happy ending were the sisters Soliana and Rica, nieces of Charlie, in whose house we stayed both times we visited Piti's family in Moustique.

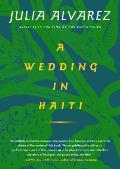

Soliana and Rica

One of the pictures I sent their mom in Florida.

©Julia Alvarez

That first weary night in the middle of rural Haiti, those two giggly girls, about the ages of my two granddaughters, were in familiar territory. They brought water up from the river for us to bathe, and they "did our dishes" when we finished eating. At one point, I looked up at a tablet nailed above the door to the cooking hut, where someone had written ten numbers with a piece of charcoal. I assumed they were lucky lottery numbers to play at one of the banques. But the girls explained that it was their mother's cell phone number. The story unraveled. Their mother was working in Florida. The girls spoke with her regularly, but they hadn't seen each other for several years. I had snapped several photos of the girls, and they asked if I would show them to her. [See one of those photos on page 56 of the book.] This happens also in the campo in the Dominican Republic: people thinking that we in the United States live close to each other and can visit easily. I tried explaining to the girls that my home was in Vermont, far away from Florida, but I could definitely mail their mother the photos. Charlie didn't have an address, but I didn't want to disappoint the girls, so I promised I'd try.

Back in Vermont, I called the number I'd copied from the tablet nailed to the cooking hut. A woman answered in Kreyòl. She didn't speak English or Spanish. I pronounced the names of Soliana and Rica. There was a hesitation, and then a flurry of worried Kreyòl. Oh no, I thought. She thinks something has happened to her daughters. Très bien, très bien, I assured her in my rudimentary French.

For the next few days, I called at different hours. My hope was that someone in her household who knew English would answer. But the cell just rang and rang. Maybe the woman figured I was that crank caller, bothering her again.

A few days later, I told the story to my stepdaughter, the mother of my two granddaughters, whom Soliana and Rica had reminded me so much of that first night in Haiti. My stepdaughter said that her daughters' school bus driver was Haitian. She would take her cell phone to the bus stop and ask him to call.

It worked! My stepdaughter's bus driver got through to Madame Ricardo, who gave him her address, which my stepdaughter emailed to me.

According to the idea, popularized in the 1990s play Six Degrees of Separation, everybody on this planet is separated from someone they know by only six people. But in this instance, it took only three of us to reunite a mother with photographs of her kids.