This blog is off to a roaring start. My first post,

Attention Must Be Paid, took its title from a famous line in

Death of a Salesman. Yet no attention was paid me whatsoever. I really am the Willy Loman of book salesmanship.

Then, on day two, I told of a conversation with a librarian friend, whom I consider witty and winsome. This time I did provoke a strong reaction ? from my friend. She accused me of portraying her as a waspish crone who drinks dandelion wine and disapproves of James Joyce and any other example of modernity. The sole reader comment on yesterday's post suggests as much. I have therefore appended a correction/amplification* below.

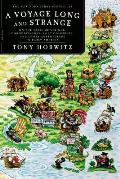

Since I as yet show no signs of swine flu, which would allow me to malinger and die in order to escape further embarrassment on this blog, I'll move today to safer ground: the distant past. That's the principal subject of my book, A Voyage Long and Strange. It opens with a visit to Plymouth Rock, where I learn that most Americans, including myself, know almost nothing about the pre-Mayflower history of this continent. So I set off to rediscover early America, in the archives and on the road, following the trail of Vikings, conquistadors, and other adventurers who encountered this land and its native people long before the Pilgrims landed.

Most of the history in the book is taken from the accounts of early explorers, who describe the wonders of a world utterly new to them. Creatures we regard as commonplace ? fireflies, croaking bullfrogs, opossums ? astonished Europeans who had never encountered them, and struggled even to describe what they saw. (Buffalo, shown below in an early Spanish sketch, were considered hump-backed cows with goat-like beards.)

Newcomers were also mesmerized by Native Americans, who were generally much bigger, barer, and healthier than the underfed, sea-weary, and over-dressed Europeans disembarking from boats along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. Indians were likewise astonished by the pale, hairy strangers who washed up on their shores.

"They tooke off our clothes," an English captain wrote of the Algonquians he met in 1584 on Roanoke Island, in today's North Carolina, "for they wondred marvelously at the whitenes of our skinnes, ever coveting to touch our breastes, and to view the same."

A Spaniard who traveled the Colorado River in 1540 described Indians combing his beard and patting flat the wrinkles on his shirt, perhaps thinking it skin. Natives of southern Canada were less impressed by the garlicky Frenchmen canoeing their waters.

"The Huron would not come near us nor bear the odor of our breath, declaring that it smelt too bad," a missionary wrote, adding that his hosts were also appalled by facial hair. "They think it makes people ugly and weakens their intelligence. They judge us to be very stupid by comparison to themselves."

There are dozens of these accounts, which also tell of newcomers and natives ? who usually understood nothing of each others' words ? trying to communicate by playing music, drawing pictures in the sand, exchanging gifts, and even attempting crude show-and-tell.

"With some sticks and paper I had some crosses made," a Spaniard wrote of his encounter with Indians in Arizona. "I made it clear to them that they were the things I esteemed most." One wonders what the natives made of a man who worshipped crossed twigs.

As we now know, the arrival of Europeans quickly led to the dispossession and death of millions of natives. A lot of my book is about that. But it also tells of an astonishing and unrepeatable moment in our history, when two distant branches of humanity came together ? violently colliding at times, curiously engaging in mutual discovery at others ? on the beaches, plains, rivers, and deserts of this continent.

To me, first contact is a fascinating study in human behavior, a test of people's courage, humanity, resourcefulness, and sense of humor. It's also an experience we can't have today, outside of science fiction. That's why I wanted to take the long, strange journey that became this book.

I'll end with a 16th-century illustration of Timucuans in Florida tossing a few gators and other critters on the barbie. The word "barbecue" is one of many that Indians introduced to the European lexicon in this period. They also shared their food with new arrivals, including Columbus, who in 1492 sampled iguana. He wrote, and I quote, "Tastes like chicken."

** For the record, Christina Bevilacqua is not a fusty librarian who wishes gravity had never been discovered. She drinks gin, wears red lipstick every waking hour, is addicted to the Arctic Monkeys, and has a picture of Proust along with Poe's inside the locket I described. Her dance card is full. And, in response to a reader's comment, she venerates 1838 precisely because it represented an end to the era when only the well-bred were well-read. Christina adds: "even the common man of that era would have known to use the conditional tense when constructing a sentence about what might or might not have happened if the subject of his sentence had been alive in another era. I regret that yesterday's commentator on this blog cannot claim similar ability, since perhaps a skillful wielding of the language would have enlivened the reader's knee-jerk response."