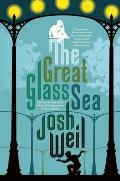

Dima and Yarik are twin brothers in a Russia set in a slightly alternate universe, in the city of Petroplavilsk. The city is in perpetual daylight, thanks to the Oranzheria — a "sea of glass" greenhouse built over farmlands lit by mirrors in space. Though inseparable in childhood, Dima and Yarik begin to take radically different paths as they navigate adulthood, family, responsibility, and ideology.

The Great Glass Sea, the first novel by "5 Under 35" winner Josh Weil, is steeped in Russian folklore and fable, and is a moving and ingenious tale of familial love.

Library Journal calls it "resplendent and incandescent," and

Lauren Groff exclaims, "

The Great Glass Sea is our world made uncanny: the Russian countryside of folktale and literature turned darkly luminous, menacing, and brittle. I was intoxicated by this novel's brains and I fell hopelessly in love with its heart. Josh Weil is a spectacular talent." We were so impressed with it, we chose it for our

Indiespensable Volume 48.

÷ ÷ ÷

Jill Owens: In your first book, The New Valley, you write very movingly about rural Virginia; it plays a huge part in those novellas. Place is also a huge part of the new book, but it's a radically different setting. What made you want to write about somewhere so different? How do you think about place in your fiction?

Josh Weil: Those are two really important and big questions. First of all, I didn't necessarily choose to write about it. It really was something that had been in me for a long time, ever since I spent time in Russia and the Soviet Union when I was young, and then Russian club and my Russian language classes all throughout high school took over my life in a big way. So it was a place that was very present in my mind ever since I was a kid. Because of that, I always knew I'd write about the region at some point.

Josh Weil: Those are two really important and big questions. First of all, I didn't necessarily choose to write about it. It really was something that had been in me for a long time, ever since I spent time in Russia and the Soviet Union when I was young, and then Russian club and my Russian language classes all throughout high school took over my life in a big way. So it was a place that was very present in my mind ever since I was a kid. Because of that, I always knew I'd write about the region at some point.

When I started writing, I thought it would be a short story. I wrote the opening paragraph pretty much as it is in the book now. When I started to get into the scene, I realized it was going to be something longer and put it away. But it clung to me.

It was through the landscape in my mind that the story really gripped me, more than any real understanding of the Russian landscape. In a way, it was very different from Virginia in that I didn't know the landscape as well but the place was my way in. And so a lot of it was imagining that setting. Then, of course, you start to do research. I went back to Russia to try to get some of those physical details that might have eluded me otherwise. It starts to become alive.

The idea of place and the importance of place has always been so, so vital in making the world feel real. At the same time, it's also how I often wind my way into a story. In some ways, it's a crutch for me. It's something I have to watch myself for. My writer friends who have been reading my work for 10 or 15 years always say, "I know Josh is struggling with this scene because he's writing about the clouds again." It's just a way that I can grab something that feels solid, that allows me to pull myself into the moment if I'm struggling. I go through and have to pare a lot of that out, but because of that, place is a grounding element for me.

Jill: How did you end up spending time in Russia as a child?

Weil: I was on a student exchange. I stayed with a host family in the far northern city of Petrozavodsk, which is obviously what Petroplavilsk is modeled after. I changed a lot of the names, but just slightly. My family on my mother's side is all Russian Jews. My mom used to put Russian folk songs and Eastern European folk songs on the record player and teach me dance steps, and we'd dance around the living room. My great-great-uncle, who is very important to me, grew up in a home where American Communists would meet. So there was always this element that was buried deep inside me about Russia.

Then when I went to junior high school, I was lucky enough that my school had a Russian language program. And this girl who I had a crush on decided to take a Russian class. That's the main reason I wound up taking Russian, but I stuck with it for six years. It became a huge part of me. Then I went on a student exchange and lived as a host student in the Soviet Union — the last year, actually, that it was the Soviet Union. I was 14.

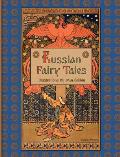

Jill: There's a strong influence of Russian folktales and fairy tales throughout the book — for Dima in particular, but it colors both brothers' lives. I grew up reading those stories, and I love how you incorporate the images and the language. Why did you want to make those tales a focus in a work about a futuristic Russia?

Weil: I never, ever thought of this novel as a science fiction novel, or even really a futuristic novel. It's funny that it has gotten placed in those realms. It shocks me because I don't know that I've ever even read a science fiction novel.

For me, instead, it felt like a fable. I didn't want to write something that was set in a world that was so far detached from our own as a fable would be, but I wanted to write something that felt like our own world, as close as possible, and yet freed from only the constraints that would have kept it from being the story I wanted it to be.

What struck me about it was this idea of writing something that had the tone or the feel of a fable but was rooted in realism. So that's how I thought about it. I think it probably has to do, too, with the very fact that I don't know Russia that well. Even though I was there as a kid, studied it for years, and went back to do my due diligence and research, I didn't know it so well that I felt that I could write the real Russia today. I would have failed if I tried to do it, and it would have been arrogant of me to try.

In a way, setting it within fables was important for two reasons. One, it freed me up to feel like I could write about Russia because I was writing something that was so obviously not claiming to reveal Russia's soul as it is now in 2014. But also, my relationship with Russia had been one that was created half in my mind. So, it was my own private fable of Russia, if that makes sense.

Jill: What kind of research did you end up doing on the mirrors themselves and the greenhouse, and what their effects on the ecosystem, plants, animals, etcetera would have been?

Weil: I did a fair amount of research on that — two different kinds. One was the kind that I did before getting into a lot of the meat of the writing, which dealt with the ideas more, so I was reading about different philosophies around socialism and communism, or looking at ideas of leisure and what's happened in American capitalism. That kind of stuff I did as preparatory research.

The other stuff that you're talking about I did only as much as was necessary in order to get the world to work. I didn't want it to become, for exactly the reasons I was talking about before, a science fiction novel. I didn't want it to become about those things.

I guess what got me started on this — the first inklings of an idea — came from a short story that I wrote, which I had just stumbled upon. I had been listening to an NPR interview with an author who was writing a book about nighttime, and he just happened to mention in one sentence that the Russians had sent up these experimental satellites to try to light the northern cities 24/7 with reflected sunlight. I thought, That is crazy. That is so crazy cool. So I started digging around and trying to find what I could find about that.

I wound up writing a short story that became kind of an anchoring story in the collection that will probably be out next year, or in 18 months. It's called "The Age of Perpetual Light" and it's about that idea. This novel was actually originally going to be a story in that collection, so it did begin with the space mirrors. Then, because it had been Russians who'd sent up these experimental space mirrors in '93 and '96, I believe, I wanted to set it in Russia. So that's kind of how the story started to take shape.

I wound up writing a short story that became kind of an anchoring story in the collection that will probably be out next year, or in 18 months. It's called "The Age of Perpetual Light" and it's about that idea. This novel was actually originally going to be a story in that collection, so it did begin with the space mirrors. Then, because it had been Russians who'd sent up these experimental space mirrors in '93 and '96, I believe, I wanted to set it in Russia. So that's kind of how the story started to take shape.

After that, I dug around and found some people — professors at universities, that kind of thing — who knew stuff about space and satellites, especially photoperiodism and the effects of circadian rhythms on plants and animals. I wound up just talking to people who knew this stuff, which is one of the amazing things that you find as a writer. If you do any research, you find that people are so happy to talk to you and share their expertise. I'm always shocked by that. I'm so busy, and they're probably even busier, but they take the time to talk for 10 minutes, and you can learn a tremendous amount in 10 minutes if you're talking to someone who's done years and years of research in your subject.

Jill: As you mentioned, it is a novel about ideas as well, about communism and capitalism and leisure and the point of work, and the point of life, really. How did you think about incorporating those aspects into the novel?

Weil: It was tricky. I'm always really, really wary of novels of ideas, especially when those ideas are pushed to the fore and aren't buried, and yet I knew that what was tearing the two brothers apart in this was going to have to do with their approaches to ideas about how you live your life, and those ideas are rooted in some very big philosophical problems.

It felt integral to me to the heart of the emotional storyline, which is where I wanted to put my focus, and I felt like I couldn't really get at that without dealing with the ideas as well. That's why I kind of wound up facing those things down and trying to write about them in a way that felt like they were coming from the characters or from the necessary momentum of the story.

It was probably the thing I had to learn most with this book more than anything that I've written before — how to incorporate having ideas right there on the surface that I was going to deal with frankly, as opposed to just dealing with the emotions of characters. I hope that I managed to do it in a way that feels like it's still part of a story and not something laid upon a story.

Jill: You did. It's so integral to their trajectories that it defines the shape of the novel, in a way. Both brothers end up getting used, to some extent, to forces beyond their control, opposing forces even, and it gives the novel an almost diamond-shaped structure in my head as they're moving away from each other and then toward each other again.

Weil: Yeah, it's funny; I think part of why the brothers are used has to do with my reluctance to try to answer these philosophical questions. And, for me, when you're dealing with a novel of ideas, maybe it's just that I don't believe I have the right to claim to have some real truth at my fingertips. The way that I approached these ideas was to try to peel them apart and wrestle with them, and not necessarily come to any solid solution through them.

There are other characters who believe that they have the right ideas and the right solutions, and they're the ones who manipulate the brothers. But neither of the brothers have a sense that this is the only and right way to live your life, this is the answer to these philosophical questions. Because of that, they wind up being manipulated by other people who think they do have the answers, and I find myself on the brothers' side, closer to them than to the more sure-footed characters around them.

Jill: As you were saying, a huge part — maybe the biggest part — of the novel is concerned with the relationship and the love between the two brothers.

Weil: That's the heart of it for me. That's why I wanted to write it.

Jill: What interested you about that kind of familial bond, especially between twins?

Weil: Well, honestly, the fact that they're twins was something that came out of the story. As I started to realize I was going to be writing about this world of light and dark, and that they could be working opposite shifts — one during daylight, one during mirror light — and the ways that their lives would begin to mirror each other, I wanted to make them twins.

But the guts of this for me really is the relationship between the two brothers. I have an older brother and we grew up extremely close; he was something of a father figure to me. I have a great father, but my parents were divorced when I was about four and a half, and my brother and my mother and I moved away, so I only saw my father once a month.

Jill: How much older is your brother?

Weil: He's five years older, and he became very much my rock growing up, and then it kind of just shifted into a relationship where we were more equals. We stayed extremely close until the pressures of adult life began to intrude — and by that I just mean the inevitable ways that life becomes more complicated as you move out of childhood and into adulthood, whether it's pursuing careers or getting married or having kids, or all of these different things. They make your relationships more rich, but because you've thrown a wider net over all the things in your life, that can threaten the sole place that an early relationship can have. That tension is something that my brother and I have managed to navigate so that we're both still very close and love each other a lot.

I'm married. He's married. He has a daughter. I have a stepdaughter and a son on the way. We've managed to make it through that and still hold onto the bond between us, but it's been hard. And that wrestling with it, and the pain and the sadness that comes from seeing something so important to you morph, and having to shape it around the realities of life, is something that I wanted to write

about.

Obviously these two brothers, these twins, are very different from my brother and me, but the core of what's threatening the relationship, and the way that they deal with it, springs from the germ of what's between my brother and me.

Jill: One of the central questions in the book is: What's the importance of and the debt to family? Whether it's the brothers' relationship with their mother, or Yarik's relationship with his wife and his children, or their relationship with their uncle, that question runs throughout the book.

Weil: It's probably such a strong part of the book because, in some ways, it's the most painful and difficult one to deal with, and I usually think that that's where to look in the book for where its real heart is. When I set out on a subject, I'm always asking myself what scares me most about it, and that's where I want to put my focus. I want to try to bore down on that.

The truth of this is that idea — why we feel the need to branch out from one kind of relationship into another one — is kind of a terrifying one to try to grapple with, for me at least. Just between you and me, and all of the readers, I think that I probably could've been just as happy being a weird old dude living with my brother in a cabin somewhere, having just a wonderful bond that had continued right from childhood on to death. We would've missed out on all of the other rich kinds of loves and relationships that are out there. I know that neither of us would trade what we have for that, but that's not the same as saying that we wouldn't also have been happy that way.

So looking at the choices that we make and why we make them, what the pressures in society are, where in society we learn what's okay and what's not, and how that pushes us towards certain decisions and away from other ways that we could have lived life, that's very fraught with a lot of difficulty for me. I think that's why the book circles those issues in so many different ways.

Jill: One question that's connected to the larger philosophical ideas, and maybe it's connected to the fable-like nature of the book, too, is what is the role of art in our lives? Where can that be important as well?

Jill: One question that's connected to the larger philosophical ideas, and maybe it's connected to the fable-like nature of the book, too, is what is the role of art in our lives? Where can that be important as well?

Weil: Yes, absolutely, and that's part of why Dima's reciting of the Pushkin poem becomes such a powerful draw and has such an effect on the community. Again, you're right, it ties into the kind of philosophical ideas that I wanted to wrestle with, in that art, in many ways, is the least justifiable thing in a society that values productivity and usefulness. It's less tangible in what it does for people, what it means for people, how it benefits a society.

We see that in our own society, with whether you're looking at the emphasis on math and science in schools or arts programs being cut. I mean, my own father, who has been terrifically supportive of me throughout my life, is a scientist, and he often just chuckles at what he sees as such a sweet deal that writers have, that I'm being paid to come and talk to some people at a college and give a reading. He just thinks it's so cushy because the hard work of it is not as definable as it is when you're in a lab.

I wanted to deal with an element of that. If we are so focused on producing, producing, producing and so focused on having tangible results for our labors, where does art fit into that and what gets lost when there's no time for it?

Jill: I like that the specter of American workers is invoked by both sides. One side is saying, "We need to get the workers to be more like American workers and be incredibly productive and not have any leisure time," and the other side is saying, "That's horrible. We don't want to end up like that at all."

Weil: Well, I think it's a scary thing, the American worker. If you look at what's happened — I don't have the numbers at my fingertips — but the American worker in the past 20, 30 years has, I think, become at least twice as productive, perhaps more. The productivity rate has just skyrocketed, and at the same time, the typical American worker is working many, many more hours. We're talking in aggregate at least a month's worth of more work for workers who are more productive.

It seems like certainly the middle class, and the working class, and probably white-collar workers, too, feel more pressed for time and more desperate and more constantly scrambling to stay afloat.

How that happened was something that was really confusing to me. It felt like a big problem that everyone was turning away from, so I wanted to look at that and say, "Are there other ways of thinking about this?"

Just recently I heard that Keynes had predicted that certainly by now, and actually before now, we would have a 15-hour workweek and that the main problem would be doing a better job than the aristocracy had done of using our leisure time effectively, in ways that weren't going to be wasted, and that would be the main problem people would have.

How did we go from someone like Keynes, who is so at the heart of our understanding of capitalism, to where we are now? How did he get it so wrong, or what did we do so wrong that pushed us in that direction?

Again, I don't have the answers. I'm not an economist, far from it. I'm not a philosopher, but I can read and see what other people thought. You can even look at Bill McKibben and his work about local economies and looking not at growth as the main thing that keeps us moving but satisfaction in life. I would just read up and look at what other people were thinking and say, "Hmm, how can I incorporate that into what's pressing on my characters' lives?"

Jill: Both of your books have drawings in them. They look almost like schematics in one of the novellas in your first book, and then you have drawings that begin every chapter in The Great Glass Sea. Why did you want to include those, and what do you see as their relationship to the text?

Weil: It's something that I've been interested in for a while. Probably, if you want to go really far back into things like Treasure Island and the books I would read as a little kid that had illustrations by Wyeth, stuff like that just sparked my imagination and seemed so rich.

I've always liked the way that illustrations can work with words, but I didn't want to do something that would be illustrative to the extent that it would hamper the reader's ability to come up with his or her own world in his or her mind, and the ideas of the characters, and all of that.

As an adult, I think what really struck me first was W. G. Sebald's work and the way that he would use photographs to comment on what was in the text, to lead us toward ideas, sometimes to raise questions of what was coming and make us think in different ways about what we were reading on the page and how it related to a less-clear image. The way that he used images was really, really important to me and felt like he was operating on a second level, like there were two planes and I wanted to have access to that other plane when I was writing.

With the first book, that middle novella, there were a number of reasons that I wanted to use images there. One was that it dealt with time in a way that was very fluid. At about 100 pages long, I knew it needed to have sections that were broken up, but the kind of hard stop of a chapter break or a number or a line felt too concrete for the way that novella worked, whereas what I love about images in books is that you see them coming. You can still glance back at them as you're moving on. They're more fluid.

It fit the requirements of that story. There were other ways that those particular images also fit that story, and the fact that I wound up drawing them just happened to be a fluke. I'd initially pulled images from old tractor manuals, which, if you haven't read that novella, makes no sense. [Laughter] But I was pulling them from old tractor manuals because I'd noticed that oftentimes, the cross sections of different engine parts would look like posters in doctors' offices, and it fit the needs of the novella for that.

Then Grove, my publisher, had their lawyers saying, "We don't know how we're going to find permissions for these old tractor manuals, and I don't know if we can do it." I said, "Well, let me try to draw something," and that's really how that came about. Everyone at Grove liked the drawings, and it was great fun for me to get to do them.

With this novel, again, it was the pressures of the novel that led me to feel like the drawings would help. In this instance, it was that I wanted it to be very clear, as clear as possible, that this was not meant to be a hard realism of Russia now, and that it should have a feeling of a fable. When I thought about fables, I couldn't separate the fable from the illustrations of a fable in my mind.

When I think about Russian fables, they're completely intertwined with Ivan Bilibin's images, so I wanted to have something that kind of led the reader in that same direction. From the first moment of opening the book, the reader would feel like he or she were entering a fable, and the illustrations felt like the least heavy-handed and, at the same time, most effective way to do that, so that's largely why each chapter begins with one. They're clearly and heavily inspired by Bilibin and nowhere near the kind of work that he could do.

When I think about Russian fables, they're completely intertwined with Ivan Bilibin's images, so I wanted to have something that kind of led the reader in that same direction. From the first moment of opening the book, the reader would feel like he or she were entering a fable, and the illustrations felt like the least heavy-handed and, at the same time, most effective way to do that, so that's largely why each chapter begins with one. They're clearly and heavily inspired by Bilibin and nowhere near the kind of work that he could do.

Jill: Lastly, what are you reading and enjoying lately?

Weil: A bunch of different things. Not really any Russian literature, although I am reading Anna Karenina because I actually had never read it and I thought, Boy, I better do that. I'm enjoying the hell out of it. I think it's something that I've enjoyed more than anything else in a while.

There's a book that I'm reading for the second time. I read it when it was in a galley, and I'm reading it now, when it's changed a little bit, called In the Course of Human Events by Mike Harvkey. I think it's really brave, and that's something I look for in books. I'm looking forward to reading Anthony Doerr's All the Light We Cannot See. And I've been reading a bunch of Isaac Babel. I guess I am reading more Russian stuff than I thought, but the novella I'm working on right now is set among the Cossacks about 200 years ago in Russia, so I've been reading Babel.