The word "idiom" originates in the Greek word

ídios ("one's own") and means "special feature" or "special phrasing." Idioms are peculiar because, by definition, something that is one's own is impossible to translate or share. Idioms point to ideologies inherently foreign and strange. Taken word for word, they are often ridiculous and hilarious.

But translating idioms verbatim is also a poetic exercise that reveals how language can build a universe and retain a history particular to a people. Idioms are vivid, rich, linguistic artifacts, and they are responsible for my early love of language.

Here are five Greek idioms that might "change your lights," too.

1. "You want me to smell my fingers?"

As a statement, might appear as "Ta µ???s? ta d??t??? µ??."

Also phrased as "Ta µ???s? ta ????a µ??," meaning, "I will smell my nails."

The English equivalent is akin to "I'm not a mind reader" — but this isn't something I understood as a kid, and I couldn't figure out why my father was asking if he should smell his fingers. Did he want us to smell them, too? What was on them, exactly, and why was anybody smelling their fingers?!

The idiom has its roots in Ancient Greece. Serious gamblers consulted the oracles before placing their bets in the Olympic Games. The priestesses, before delivering their prophesies, would dip their fingers in an oil made of laurel extract. Then they fell into a kind of trance or sleep (or drunkenness), which somehow informed their predictions. The smelling of the tips of fingers followed and was apparently crucial to making a prediction.

Nowadays, because we Greeks are a highly gestural people, some people even bring their fingertips to their noses.

2. "Let's go to up the mountain"

"??µe st? ß????" / "We go to the mountain"

I had no idea what the hell was happening in 2007 when I brought my future wife, Sara, (as far as my family knew, she was just a friend) to Crete. We spent a few days on my grandparents' farm, and at the end of the trip my Theo Panayiotis insisted we "paµe st? ß????." I was relearning Greek as an adult, and as a result I missed some of the subtleties of the language: I misinterpreted the colloquial phrase of "let's go out" to mean "let's take a walk up the mountain." As it got darker, Sara got freaked out like: what mountain is your uncle trying to take us to tonight?

Instead, my Swedish-looking theo brought us to a gorgeous restaurant overlooking the Aegean, where we ate a true Greek family-style meal, with the ratio of plates to people reaching 3:1. That's the only kind of mountain climbing we modern Greeks do these days.

3. "He sold him seaweed for silk ribbons."

"??? p????se f???a ??a µeta??t?? ???d??e?"

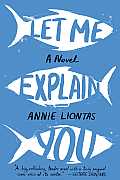

It's obvious with this one that you were — as my protagonist in Let Me Explain You, Stavros Stavros Mavrakis, might say — Suckers 100%. You got something worthless in exchange for a lot of money, or someone promised you something that in the end proved to be negligible. For Stavros, the seaweed is the woman he is betrothed to in an arranged marriage. He's told he's getting a good Greek girl, a virgin, a chance at a real American future, but what he inherits is a life he never wanted for himself.

This idiom is also used when people oversell themselves — a definitively Greek practice — or when they lie like a Greek lies, which is exaggeration, which is not lying at all, really.

4. "I'll put your two feet in one shoe"

"?a s?? ß??? ta d?? p?d?a se e?a pap??ts?."

("I'll put you in your place.")

Greeks aren't shy about making threats, as this idiom suggests — and when they really mean it, there is often reference to testicles. But I've always associated this particular idiom with our "between a rock and a hard place." Less of a threat, more of an appeal for understanding and compassion.

In Let Me Explain You, Stavros often finds himself with his two feet in one shoe — when he must choose between his daughters and his dreams for a better life, when he must choose between his pride and the woman he loves, and most of all when he must choose between life and death.

5. "I ate the whole world to find you."

"?fa?a t?? ??sµ? ?a se ß??."

("I tore this place apart looking for you.")

This might be my favorite idiom of all. There is something so intimate and true in the connection between searching and consuming.

In Let Me Explain You, Stavroula searches for her missing father. When there is nowhere else to go, when she has nowhere else to turn to, she ends up at July's house — her boss's daughter and the woman she pines for. Then Stavroula and July do what people do in times of crisis when all there is left to do is wait — they eat. Together they prepare a rack of lamb, dipping crusty bread into the drippings. Stavroula, who has eaten the whole world to find her father, also eats the whole world to find love.