I've had three Deep Throats in my Oregon literary career. Each put me on to something incredible that enriched my recounting of modern Oregon history.

For the uninitiated, Deep Throat was the code name of the legendarily secret source who helped Woodward and Bernstein unravel Watergate and overthrow a paranoid criminal in the White House, Richard Nixon. It's also the name of the infamous pornographic film released in 1972 that was the subject of countless legal battles for many years.

In my mind, a Deep Throat is a person in authority who is uniquely and intimately connected to a fantastic story and is willing to share but does not want to go on record. Background only. Hints. Leads. Names. Allusions. Documents you can inspect but not keep.

I met the latest one in August 2012 in the parking lot of the Newport Starbucks. We had intended on drinking tasteless corporate coffee, but an electrical fire had temporarily closed the place, so we sat outside on the patio while streams of people walked away visibly angry when they learned the horrible truth.

Deep Throat had two folders of papers in his possession. There was, indeed, a flower pot nearby (you'll have to read All the President's Men to understand that reference). He began narrating his story and how he found me through my book about the filming of Sometimes a Great Notion. The source was originally from Eugene and knew Ken Kesey well back in the creamery days and interacted with him several times in subsequent years.

"I slept on the bus," he said, relating an amusing story of visiting Kesey at Perry Lane, Kesey's bizarre bohemian community in Palo Alto during the early 1960s. "But only once. I had to get out of there before the place got raided."

I agreed it was probably a good idea to leave, and then I started firing questions. He looked me over and began answering.

As I said, I've had three Deep Throats. All were semi-elderly white men and totally unassuming in character. All were well off financially and had nothing to gain and no private agenda to advance, which was certainly not the case with Mark Felt, Woodward and Bernstein's source. After Felt died, we learned he wanted to get even with the Nixon Administration for passing him over for promotion in the FBI.

I met my first Deep Throat in 2004 by sheer accident in the Sportsman's Tavern in Pacific City while I was writing a book about Vortex I, the notorious free, state-sponsored rock festival held in McIver Park near Estacada in August 1970. I was discussing the project with a man at the bar. Deep Throat overheard us. He casually interjected and said he knew Oregon Governor Tom McCall in the 1970s and knew him well. He was on the inside. Would I like to move down the bar and hear about the real McCall and his unprecedented support of an event like Vortex?

I met my first Deep Throat in 2004 by sheer accident in the Sportsman's Tavern in Pacific City while I was writing a book about Vortex I, the notorious free, state-sponsored rock festival held in McIver Park near Estacada in August 1970. I was discussing the project with a man at the bar. Deep Throat overheard us. He casually interjected and said he knew Oregon Governor Tom McCall in the 1970s and knew him well. He was on the inside. Would I like to move down the bar and hear about the real McCall and his unprecedented support of an event like Vortex?

Yes, I would.

"Okay, I'll tell you, but I will never give my name. That's the deal. Take it or leave it," he said.

I took it.

He talked for an hour and I took notes on napkins with Oregon Keno pencils. I barely had to ask any questions.

Later, every lead panned out. Every one of his stories either confirmed someone else's or was subsequently confirmed by people who didn't know him. I couldn't attribute anything directly to him, but he shined a light into some very intriguing dark corners, particularly the problems related to McCall's drug-addicted son, Sam, who later died of an overdose.

The truly interesting thing about this Deep Throat was his belief that Vortex was an utterly trivial story, a historical nude-hippie sideshow. "C'mon! A rock festival?" he said loudly, mockingly.

As I left the tavern, he said, or I should say screamed, "I reject your thesis that Vortex matters, but don't fuck it up!"

I like to think I didn't in The Far Out Story of Vortex I.

Deep Throat number two emerged in Astoria during the time I was working on my book Red Hot and Rollin' about the 1977 Portland Trail Blazers' NBA championship team. I was there promoting the Vortex book and met a man in attendance who later told me his astonishing and completely unacknowledged role in helping the Blazers win the franchise's only title. One word: marijuana. Another word: supplier. If you ever saw how that team played or the film Fast Break, the obscure 1978 documentary about their improbable championship run, you just know this Deep Throat was telling the truth.

Deep Throat number two emerged in Astoria during the time I was working on my book Red Hot and Rollin' about the 1977 Portland Trail Blazers' NBA championship team. I was there promoting the Vortex book and met a man in attendance who later told me his astonishing and completely unacknowledged role in helping the Blazers win the franchise's only title. One word: marijuana. Another word: supplier. If you ever saw how that team played or the film Fast Break, the obscure 1978 documentary about their improbable championship run, you just know this Deep Throat was telling the truth.

Even David Halberstam didn't get the marijuana story in his classic account of the Blazers of that era, The Breaks of the Game. I made a subtle allusion to this Deep Throat's tale in my book and dearly wanted to reveal the whole wonderful stoner reality, but I gave my word and he trusted me. That's the main reason I've been successful as an Oregon writer and am able to get people to share their stories, documents, and photographs; I don't sell them out.

When Deep Throat number three started answering my questions, I knew I was onto gold. At some point in our conversation he produced a document from a folder. I read its ancient typewritten pages and could not believe that in all my research of all things Kesey, I had never seen it.

I cannot reveal its contents due to strictures of exclusivity and the fact that Kesey enthusiasts don't have easy access to his papers. All I can say is that with one check written to acquire the Ken Kesey archives and house them permanently at the University of Oregon where they spiritually belong, thereby ensuring their easy access, Duck alumnus Phil Knight could perform an infinitely more worthwhile cultural service than his continuing multimillion-dollar support of the cultural farce that is big-time University of Oregon athletics.

The document offered a small gem of a revelation, particularly in light of the fact that One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest celebrated its 50th birthday in 2012. It won't rock the literary establishment, but it is fun, and disclosing something fun is something I love doing with my writing. What an interesting notion: journalism employed to elicit joy.

Despite my pledge not to reveal the contents of the document, I can share another Kesey tale — the possible origins of the Joe Ben drowning-under-the-log scene from Sometimes a Great Notion, one of the more memorable episodes in American literature and cinema. Deep Throat told me that Kesey recalled an incident in his youth when he and his brother Chuck were rafting down the central fork of the Willamette River. A windblown tree stretched across the river and appeared to block passage. The Kesey brothers attempted floating under the tree but the raft got hung up. Chuck was somehow trapped, somewhat submerged in the current, at risk of drowning. Ken managed to pull himself free and puncture the raft with his knife, and Chuck came free.

Despite my pledge not to reveal the contents of the document, I can share another Kesey tale — the possible origins of the Joe Ben drowning-under-the-log scene from Sometimes a Great Notion, one of the more memorable episodes in American literature and cinema. Deep Throat told me that Kesey recalled an incident in his youth when he and his brother Chuck were rafting down the central fork of the Willamette River. A windblown tree stretched across the river and appeared to block passage. The Kesey brothers attempted floating under the tree but the raft got hung up. Chuck was somehow trapped, somewhat submerged in the current, at risk of drowning. Ken managed to pull himself free and puncture the raft with his knife, and Chuck came free.

I have no idea if this story is true, but it makes sense as far as providing Kesey the inspiration to fictionalize it. The harrowing scene in the novel is so wholly original and uniquely desperate that something similar almost had to have happened to Kesey. Some things you can't make up. Whether this anecdote makes it into the forthcoming biography of Kesey is unknown. Deep Throat can't remember if he told the biographer, Robert Fagan, or not.

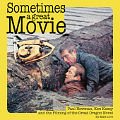

He told me, though, and I got it all down. I just wish it had made it into Sometimes a Great Movie: Paul Newman, Ken Kesey and the Filming of the Great Oregon Novel.