After September 11, 2001, my wife and I started a time capsule of sorts that we planned to open sometime years down the road, when our then theoretical kids would be at an age to be interested in their country's history.

I myself used to be enamored by the box my mom kept that contained tattered old ration books from her youth during World War II. She would explain why they rationed things like sugar and flour and described the blackouts in Los Angeles while showing me the safety pins her mother had used to hang blankets over the windows. There were packages from seeds she'd used to plant a victory garden, and copies of Time magazine and newspaper clippings that her mother had saved spanning Pearl Harbor to D-Day, victory in Europe, and the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima.

That box of memories provided me a tangible connection to World War II — my parent's generation — and instilled in me a respect for our armed services. As a teen, I delved into books that documented many of the battles and all the wars in our recent history, including Korea and especially Vietnam.

So when the terrorists attacked our country and our generation was poised for war, my wife and I collected newspapers, printed out emails we'd exchanged with friends, saved magazines like Time and Newsweek, and put aside a few mementos from our wedding, which was on September 14, 2001. We continued to add articles after our military confirmed that American soldiers were on the ground in Afghanistan in late October, 2001. We were glued to the television as tiny bits and pieces of news circulated through — grainy night-vision footage of an Army Ranger raid on an airfield in Southern Afghanistan, pictures of Special Forces soldiers on horseback alongside the Mujahideen in the north. It was in early December that I clipped out one article about Hamid Karzai, a statesman who had been exiled by the Taliban and became a guerrilla leader. There was a photo of Karzai surrounded by a group of eleven Special Forces Green Berets, all of whom had been killed or wounded, Karzai included. The next thing I knew, Karzai was the interim leader of Afghanistan, soon to become the country's first democratically elected president. This was one of those stories I suspected would remain permanently archived deep in the bowels of the CIA.

I continued to follow the war — watching Fox and CNN and reading big publications such as the New York Times, Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times, as well as more obscure websites I could find on Google — as the focus shifted from Afghanistan to Iraq. Soon after, the time capsule was relegated to a dusty shelf in the garage.

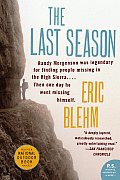

Fast-forward a few years to 2006. The Last Season was going to print, and I was trying to figure out what my next book would be. I had told my agent that I really wanted to write something about the war — I felt that it was a way I could give something back. By chance, she learned that a friend of hers worked with the sister of the captain of a Special Forces team that had been with Karzai way back in 2001.

Fast-forward a few years to 2006. The Last Season was going to print, and I was trying to figure out what my next book would be. I had told my agent that I really wanted to write something about the war — I felt that it was a way I could give something back. By chance, she learned that a friend of hers worked with the sister of the captain of a Special Forces team that had been with Karzai way back in 2001.

"Wait a minute," I said. "I remember that story." And I untaped the time capsule and skimmed the clippings from five years before.

With a little research, I learned that the story had never been told and that the captain was currently an instructor at West Point. After several phone calls to Army Public Affairs, I was able to talk to him and sit in on a couple of his classes. I told him that I was considering a story on the war in Afghanistan and that I would like to interview him about his mission there. He said that I should meet with the parents or family members of the men on his team who did not survive the mission and, if they gave their blessing to the project, that would dictate how much, if any, of the story he would share. As an officer, he would not ask his men to talk with me, but suggested I reach out to all of them. "You should hear it from as many perspectives as you can get," he said. I asked if he would provide me with the names of his men or the names of their families. At least their hometowns. He politely declined.

"You're a journalist," he said. "You found me. Figure it out."

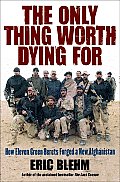

This "test" was the starting point to the journey that became The Only Thing Worth Dying For. I ultimately located the parents, who invited me to their homes. I spent a weekend sleeping in the old bedroom of one family's son, surrounded by the sad but proud memorabilia that honored his death in the line of duty, including the Silver Star and purple heart that had been presented posthumously. We sat at the kitchen table for hours. There was laughter when they recounted the good times, followed by silence. There were tears throughout days that began with coffee, shifted to beer, and ended with good whiskey. They escorted me to their son's grave, I walked on the trails where he played as a child, met his siblings, and recorded hours of interviews that took me from the soldier's birth to the moments each member of the family was informed of his death.

At the end of the weekend, I was waiting on a platform for my departing train when the father shook my hand and said, "You're going to do a good job, I have no doubt. You tell it like it happened. Don't glamorize it, don't candy-coat it, tell it like his team tells you. The good and the bad. That's how you can honor our son. That's how you can honor their mission." I looked at the mother, whose eyes were getting glossy. "Eric," she said, "I was terrified to meet you. Now I'm terrified to see you go."

After that weekend, what I knew would be an amazing story became a calling.

I boarded the train with a piece of folded notepaper folded in my pocket. The father had provided me email addresses and phone numbers of some of the other team members, who in turn introduced me to others willing to talk about their mission. I peeled back the layers of the story, all the way to just hours after the Twin Towers fell and the first meetings held in the bunker where the war plan for Afghanistan took shape. Hundreds of hours of interviews and thousands of emails later I was nearing completion when Hamid Karzai agreed to meet me. I sat face to face with him in 2008, a moving experience that became the prologue to The Only Thing Worth Dying For, which, for the record, is not an analysis of the war in Afghanistan. It's not pro-war, it's not anti-war, it's war, raw and gritty, from the perspective of men from a small team who shaped history not by design but because they were assigned the mission and because, as the men I spoke to understated it, "that's just how things worked out."

I let the father of the fallen soldier read a final draft, hoping that I'd done right by his instructions. He called me a few days later and said he couldn't stop reading, even when he wanted to, and that I'd come through for his family and the memory of his son. The only complaint he had was the most painful to hear:

"I only wish your magic pen could have rewritten the ending."