As schoolchildren, we first encounter him — Mr. Webster and his dictionary. Those fourth grade spelling tests terrified me. But

Noah Webster meant no harm when he published

A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language in 1806. He just wanted all of America to spell correctly. This mattered so much to him that in 1828 he published

An American Dictionary of the English Language. A person might think that

Dr. Johnson's dictionary was good enough. But that was English, and Mr. Webster was thoroughly American.

And so he took it upon himself to revise the King James Version of the Bible.

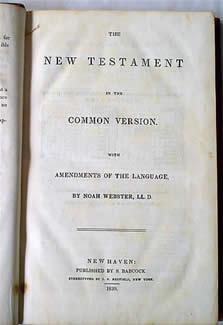

This is the title page of Webster's New Testament in the Common Version, with Amendments of the Language, published in 1839. Bibles were commonly used in schools and homes to teach children how to read, and Mr. Webster saw that the inconsistencies in spelling and the obsolescence of many of the words in the King James Version could be detrimental to the language skills of American children. (Good thing he died before texting was invented.)

He also wanted to do away with words or phrases that could offend. What did he change? In John, he changed "his body stinketh" to "his body is offensive." He substituted "vomit" for "spew" in Revelations. And, also in Revelations, "living beings" took the place of the word "beast," for there are "no beasts in Heaven," he explains in the Emendations of Language portion of his New Testament.

Mr. Webster was a New England man, and is closely associated with the towns of Hartford, New Haven, and Amherst. His home in West Hartford hosts "Tavern Nights," where guests can play 18th-century games after dinner, such as "Shove Ha'penny," which is almost certainly not something Mr. Webster would have played.

Three point two miles away sits another literary landmark, one I must mention. The Mark Twain house is a place you should visit the next time you are in Hartford. It is so fabulous (and fun!) that it has been rendered immortal in the artistic form known as Lego.

(A trivial aside: Author Brock Clarke avoids burning these two Hartford homes in his novel An Arsonist's Guide to Writers' Homes in New England.)

Noah Webster was more than just a logophile. He was political activist, essayist, and newspaper publisher. Harlow Unger unabashedly uses the word "patriot" to describe Webster in the title of his biography.

There's a story about Noah Webster that is more gossip than fact, but it illustrates something of his character: His wife, Rebecca, found him in his study in a passionate embrace with a pretty young housemaid that they employed.

"Mr. Webster," she said, "I am surprised."

"No, my dear," he replied. "I am surprised. You are astonished."