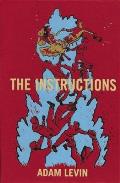

Adam Levin's debut novel,

The Instructions, is a mountain of a book — over a thousand pages long, published by McSweeney's in a single beautiful volume.

The Instructions is the story of Gurion Maccabee, a 10-year old who believes he might be the Messiah. It takes place over only four days, and includes an enormous cast of characters, an epic battle, an incredibly moving love story, and plenty of intertextual layers (which is likely, in part, what is garnering comparisons to

David Foster Wallace).

And it is awe-inspiring. Addictively quotable, violently funny, insanely intelligent, and utterly compelling, Adam Levin's debut novel will be unlike anything you've ever read, in the best possible way. The New York Observer describes it aptly: "This is a life-consuming novel, one that demands to be read feverishly. When it is over, other fiction feels insufficient, the newspaper seems irrelevant." And the St. Louis-Dispatch raves, "After The Instructions challenges, charms and betrays you, it might just seduce your soul.... This is a wunderkind's master class....An incredible creation of fiction." We are proud to choose The Instructions for Indiespensable Volume #23.

÷ ÷ ÷

Jill Owens: How did this massive undertaking begin?

Jill Owens: How did this massive undertaking begin?

Adam Levin: It began with a sentence. I wrote a sentence that isn't in the book anymore. Well, a transformed version of it is in the book. The sentence was, "I towel-snapped the ass of the Janitor." The way I go through the procedure of writing is really sentence to sentence. I wrote that sentence in Syracuse, New York, in the fall of 2001, and I thought to myself, "Who's saying that?"

I thought it was a certain kid, maybe, that I went to junior high school with, and I started writing a fight scene, which is pretty much the opening fight scene in the book, right after the waterboarding scene. But the voice was dumber than Gurion turned out to be — way dumber. It was going to be a more realistic kid. But then I quickly got bored with that, because I didn't want to write about a "realistic," cute kid, and that's what it was turning into. So I thought, "Who is this going to be? It's going to be a really smart kid." And then I thought, "Maybe he'll think he's the messiah!" [Laughter] My account of this is not that interesting, but that really is how it happened. These things occurred to me, and I chased them.

Jill: Did you realize early on how epic it was going to be, both in subject matter and length?

Levin: In terms of subject matter, that came quickly. For a very short period of time — I'm talking hours — I thought that maybe this would be an allegory about the messiah, like Cool Hand Luke, or something. But then I thought, "There's already Cool Hand Luke! There's already a great allegory." [Laughter] So I thought, if I want to do this, it should be a kid who actually suspects that he is the messiah. That has to be addressed directly, within the text, as opposed to saying, "Hey, I'm sort of talking about the messiah of the Jews, nudge nudge." At that point, I realized it was going to be epic in subject matter, because that's a big thing to write about.

But I had no idea that it was going to be a thousand pages. At the time, I certainly wasn't planning that. The book took me a long time to write, and I'm a compulsive reviser and editor. I cut way more than I keep. At a certain point — it was only about five or six years into writing it — I realized how long it was going to be.

Jill: Only about five or six years in.

Levin: [Laughter] It's all relative.

Jill: How long did it take you, overall?

Levin: The total time, including revision, was nine years. I started in fall of 2001, and I gave it to Eli at McSweeney's in April of 2009, and then we edited it for about 16 months or so.

Jill: It's quite a commitment.

Levin: In my mind, I had already written a book, because I had written a collection of stories, and I'd published a whole bunch of stories. But yes, certainly for a first novel. I don't know that I would have had that kind of commitment in 2001, if you'd told me that it was going to be that long. I think this is probably a common thing, but by the time I got to year five or six, it would have been more absurd for me to stop working on the book than to continue. I worked on it a lot, probably six hours a day. There just came a certain point when it would have felt jerky to stop. It would have been a harder thing to do, to give up on it.

Jill: There are a lot of different textual levels in the book — Gurion's detention assignments, emails, the psychological evaluations, the Commentary on Commentaries, the Story of Stories. How did you fit those elements together during the writing and revising process?

Levin: I had written a bunch of the book, around a couple hundred pages. I'd had a couple of the detention assignments in there, and I thought they were useful, but I wasn't sure how useful. One thing that I'd realized — and this changed over time — was that I had written zero flashbacks. It was semi-conscious. I didn't want to write flashbacks, partly because the speed of the book depends on not using flashbacks. Flashbacks slow things down a little bit, and I think the book's fairly fast. I eventually resolved that I could use some flashbacks, but way back when, I initially thought, "I guess I'm not going to use flashbacks, and this will be something about the book that will be interesting."

When I decided I wasn't going to use flashbacks, I had to figure out other ways to deal with the past. That's how the Story of Stories came about. The Story of Stories wasn't originally going to be as long as it is. But it got to a point where it got quite long; it's as long as any other section in the book. Then I had to make the decision: Is this going to be in there or not? Because once I have that, if that's the only thing in the book like that, then suddenly it would stick out like a sore thumb, and be sloppy form. I thought, Okay, this opens up the possibility of doing a couple of other things which are like this — long-form documents that will enhance the main text of the novel. That's not a good enough reason to write a whole bunch of other pieces like that, but I was really resistant to getting rid of the Story of Stories. By the time I finished it, I thought, "This almost stands alone. With a couple of adjustments, it could be a little novella." So I thought, "Do I want to figure out how this can fit formally into my book?" And the answer was "yes." The way that I did it was to allow myself to write some other things about Gurion's past, separately, in that sort of document form.

The assignments were already in place, and the importance of those got ramped up. The thing about my writing process is that it's really not… practical? [Laughter] I mean, it's always a lot of work. But it's not efficient, at all. It really isn't. I compulsively have to polish things, and I will have vast portions of work that I do not know whether I'm keeping or not until they're totally fucking polished. A lot of times, I will polish something into as great a shape as it can be, line by line, and still have to get rid of it. Some of those documents in the novel were really touch and go for a while, but I kept polishing them, and in the process of doing that, I was seeing how they actually fit together and how they bled into the regular text. Hopefully it's a unified piece, but I also like the idea that those longer pieces, like 9-1-1 Is a Joke and Story of Stories and Call-Me-Sandy's psychological mock-up essay, operate on their own. They obviously would need a little bit of context to stand purely on their own, like who this Gurion person might be, but hopefully not a whole lot.

Jill: You said earlier that you think about language sentence by sentence, and I was wondering how you thought about the book on that level while also keeping track of this enormous, propulsive plot and immense cast of characters.

Levin: Honestly, this is where I kind of shrug and get mystical about it. [Laughter] I religiously chase language down, and chase voice down. I think, in doing so, plot comes out of that. I think tight plot arises from a very rigorous attention being paid to voice. Maybe that sounds too general, but for me that's how it works. The stories I've written that work, and I think The Instructions works in this way, too, work because I'm constantly obeying the voice. I'm going towards what is going to be the exciting thing to do on a sentence level, and whatever that is dictates what can happen on a plot level. After a certain point, they delimit each other in a neat way. The language can't go in a certain direction because the plot is taking the book to a certain place, and the plot can't go in a certain direction because the narrator can't speak in that direction, because he's been defined a certain way.

The short answer to the question is that it's really, really hard for me to write. [Laughter] And probably the reason is because I don't know the answer to these questions. Does that make sense?

Jill: Yes, it makes sense. I also love the occasional semi-invented metaphorical language Gurion uses: snat, caulk, trickle, bancer, etc. How did you come up with those words?

Levin: Some of it came about because I'm foul-mouthed. As a kid, I was really foul-mouthed. My mom is Israeli, and Israelis curse in Arabic. And Arabs curse beautifully; they curse these wildly long amazing curses. You stub your toe, and the rock you stub your toe on gets the most vile things said to it. In America, to my mom, the word "fuck" is nothing. My mom said the word "fuck" a lot, so I said "fuck" a lot.

Jill: I'm reminded of Vincie explaining himself, why he curses so much, to Gurion, in the book.

Levin: Yes! And there's another part of the book where Gurion is cursing at Schecter, one of those long, vile, Arabic-type curses. I never learned how to do that as a kid, unfortunately, because those are some really great curses. Anyway, so you take a word like "bancer," which actually apparently means something. I knew a kid in college who told me, "I called a kid a bancer once." I don't remember if we were on drugs, or what, but it always stuck with me. It sounds really condemning while also being really funny-sounding. So I thought, "I'm going to use 'bancer.'"

"Snat" and "trickle" and that whole vocabulary came about because I wanted to talk about something that was essentially familiar, but I didn't want to talk about it in a familiar way. I didn't want snat to be honor, exactly. I thought, "What if I quantify this as though it's a physical thing, and then come up with a word that sounds sort of nasty?" [Laughter]

The names, like Dumont and Chomsky, just betray Gurion's biases. Things that are shitty are going to be chomsky, and people or situations that are dim are going to be dumont because of Margaret Dumont's character in the Marx brothers.

After I decided that I couldn't have Gurion swearing all the time and came up with first couple of words, it became fairly easy. I think the only thing I had to worry about was overkill.

Jill: Why did you structure the novel over four days, which is such a compressed period of time?

Levin: That's just how it went. George Saunders, my teacher in grad school, said that a writer's style is often determined by what they're bad at. I don't know if I'm bad at this anymore, because it's been awhile since I started the book, but one thing I was bad about was that I can get really uptight about matters of time. I haven't obsessed about this in a very long time, because it was more a short story issue, but it bled over into writing the novel. I would think, "How many words am I spending on X amount of time? If I spend two pages on one minute, and then I have some white space because it's 30 minutes later, and then I spend three pages on four years, is that okay?" [Laughter] They're really goofball hang-ups, and when I think about them now, they seem silly. But when I was starting the book, they seemed very relevant.

When I started the book, I think the idea I had was that I was going to account for every moment that Gurion was awake during whatever timeframe I used. I think I sort of do that; I get a little cheap with Wednesday. But then it was just the pace that got set.

Jill: Did you use any sort of map or charts to keep everyone straight, particularly during the battle scenes at the end?

Levin: I used visual maps of the school, like the ones that are in the book. They're a little better designed; I made them in Microsoft Word and then turned them in to Julian Birchman, and he made them really pretty. He simplified a few of them along the way; we went back and forth about it. Mine were a lot denser. There were a lot of repeated words, repeated type; if there was a room, it would say "ROOM" in a rectangle, over and over. It would be filled with "ROOM." Because… I'm an idiot. [Laughter] I would make these little OCD-type things in Word, which is not a very responsive program to make diagrams in. I had text boxes on top of text boxes.

But with the Damage proper, if you were to blow up a map of the pipeline and the gymnasium on Friday, and take little soldiers representing each of the characters and put them in the places where I say they are and move them around accordingly, it would all work out. I was really OCD about that, probably unnecessarily so. I don't think anyone cares. [Laughter] I mean, it was dorky. It was to the point that my editors were making fun of me. When we were editing that scene, every tiny thing that might change… Eli's a genius, so if he told me to cut something, nine times out of 10 — well, maybe not nine times out of 10 — [Laughter] but often, I'd listen to him. But in that scene, he would cut stuff, and it would drive me batshit, because then I'd have to check how it pulsed out through the rest of the scene. I'd have to think, "Okay, then now I have to move this guy over here, and move this guy back here..." It was really dorky. It was some Francis Ford Coppola Apocalypse Now-type shit.

Jill: How did you decide on "damage," both the word and the concept, as this unifying principle? It's a really powerful and heartbreaking one, and it obviously widens in scope throughout the book.

Levin: The word itself was a hard one for me to choose, because "damage" is a little bit heavy, as a word. I thought of different possible words for damage, and none of them were any better. Damage seemed a little dramatic, I guess. But at the same time, anything you can substitute in for it does the same thing, and the word "damage" ultimately won out.

As far as the concept goes, there's this idea that Jews have, tikkun olam, which means "repairing the world." It's a pretty cool idea. It's like, the world is a blemish on the face of God, which sounds really ugly and callous, but it means that the world is this one little fucked-up part of a perfect being. The beauty of it is that it's self-repairing; we as a community of Jews are in charge of repairing it, to make it better for God. And Gurion embraces that idea. The way he embraces it is by saying, "Yes, we do have to fix the damage, and the way we fix the damage is by damaging." So it does create a lot of nihilistic-looking behavior, but Gurion's really earnest about it.

When we get into any kind of moral dilemmas — for example, whenever we think about when it's right to go to war, some people think it's never right to go to war, but I think a lot of people do think there are good times to go to war. That's interesting to me. I probably do, too; I'm not someone who has the answers to these things, otherwise I wouldn't have written the novel. But if someone is committing genocide, we should go fucking kill them. I will say that 10 out of 10 times. If it's like, "There's a guy committing genocide over there, and we have an army that can kill the guy. Should we do it?" I'll say, "Yes, we should." I'm that person. Short of that, it's not so easy. I'm not a hawkish dude.

Even that is an interesting point. Why am I drawing this line at genocide? I mean, obviously, it's genocide, it's awful. But there are a lot of things that are awful. Gurion has a lower tolerance for the awful than other people.

Jill: In relation to that, I was wondering if one of the reasons you wanted to write about children was that they do so often have that sense of righteousness, that purity and intensity of emotion.

Levin: Totally. I mean, in one sense, the book is not a realistic novel at all, in the sense that no kid is as smart as Gurion, let alone the fact that he has all these friends that are, too. Even the dickheads in the book are pretty smart. Even Desormie is a little smart. But emotionally, I think it is kind of realistic. The thing about kids, emotionally, is that they can be extremely ideological and wholly dedicated to things in a way that adults can't.

That gets discussed at the dinner table between Gurion's parents. Tamar berates Judah a little bit for defending anti-Semites, saying that only adults could conceive of this idea of protecting freedom of speech at the cost of their own blood. Kids — and not just kids, teenagers — are always going to be more capable of this kind of thing than adults. They're there to be inspired. Adults are herded, and kids are lit. [Laughter]

Jill: It's sometimes easy to forget that the characters are kids, and then you have that moment when Gurion's mom hands him his lunch, and he looks to see what she's made for him. You remember, "Right. Gurion's leading this revolution, but he's a 10-year-old whose mom still makes his lunch."

Levin: Right. [Laughter]

Jill: Were you particularly interested in Torah scholarship and exegesis when you were a kid?

Levin: Yeah, when I was a little kid. I had an apparently uncommon Hebrew school experience; just about every other year in Hebrew school, I loved it. I had some really crappy teachers and then I had some really, really great teachers, some of the best teachers I've ever had. They would indulge any bit of questioning of minutiae. They were happy to talk about any question. There was never a "I'll shut you down because I'm scared to reveal what I don't know" kind of attitude with those teachers. That certainly got me thinking a lot about Judaism as a kid. I'd ask crazy questions, and I'd get crazy answers, and that was exciting.

But I think that by sixth or seventh grade, I caught the book bug. I really liked reading Kurt Vonnegut. I wanted to pick apart Kurt Vonnegut in the way that I had been thinking about Torah.

Jill: I've read in some other interviews and things you've written that it's fairly common for Jewish boys to think they might be the messiah. When did you know for sure that you weren't?

Levin: I still don't know for sure. [Laughter] I think it was when I was 13. Basically it was the first time I kissed a girl. I'd been into girls since I was very young. I think I was very early to have painful, intense crushes on girls. It was great, but I didn't know how to talk to them. And in eighth grade, suddenly I kissed a girl, and that changed something. It sounds really dorky, but it was like, "Oh! This is what I want to do." [Laughter] You know, you fantasize about kissing girls, and then the reality is much better than the fantasy. So in the messiah fantasy, you kiss girls and then you lead men. But in reality, you just want to keep on kissing girls. I was like, "I don't need to lead men! This is great on its own." [Laughter]

Jill: In that vein, the love story between Gurion and June is one of the most honest and accurate and wonderful love stories I've read in a long time, including their kisses — which then feels a little strange that they're both 10 years old.

Levin: Like a lot of other stuff in the book, my approach was to not let anyone be cute. I think there is still some cuteness, but it was very important for me not to let Gurion be cute, or at least conventionally cute. When you think of a 10-year-old who you like in moments, it's hard not to think they're sort of cute. But not, like, "Oh, he's chubby and talks funny and I want to give him a hug." That's not Gurion.

When I approached the kiss, I wanted it to be like your first kiss, rather than cute 10-year-olds kissing. What I didn't want was for it to be like, "Here's a valentine!" "Thank you! Let's kiss!" I didn't want that. June's really complicated, you know? And Gurion's certainly really complicated. I think that's part of the reason they're attracted to one another. And it's weird to think about 10-year-olds being attracted to one another, as an adult. But I know that, as a 10-year-old, I was definitely attracted to girls, and girls were... not attracted to me, but to other boys. [Laughter] So I think, they're going to be attracted to each other, and they're smart kids. They're able to express themselves in ways that real-life people aren't, so I let them do that.

Jill: I love the letter that Benji, Gurion's best friend, sends to Gurion after their fight. His concept of loyalty, and his prioritizing it above all else, seems to illustrate a central theme of the book.

Levin: Thank you. That's something that I naturally think about, for lack of a better term. I always assume that stuff that feels natural to me is cultural stuff, which is to say American stuff. Loyalty is a virtue we are constantly thinking about in this country. Look at the way the term "patriot" has been thrown around during the last 10 years — and that's just on a sort of boring, political level.

But if you look at the kind of entertainment that we have, and what it's really about, the great American contribution to the genre is gangster shit. And gangster shit is all loyalty. At least, it has been ever since The Godfather. The drama is all based on loyalty. In The Sopranosn, the arc of every season is who's going to be disloyal to Tony. We don't even realize that that's the arc of every season. We just think it's about being human, until it's happened six times and we realize the formula.

I think with Judaism, and with anything that has tribal roots, this is an enormous concern. It's a really interesting question, when to stop being loyal. This comes up; this is nothing new. Think about the whistle-blowing culture, and the fact that it's a big deal when someone's a whistle blower. Why is it a big deal? Because someone's betraying loyalty. I think, for a lot of Americans, when we watch a gangster movie and the thief turns in the murderer, we're like, "Thief, you're a piece of shit! You shouldn't have turned in that murderer." And that's really weird! [Laughter] But it's really visceral. He's the bad guy because he dicked over his friend.

There's a certain point at which I'm confident that there's too much loyalty. The question is what it is, or where it is, and where we allow exceptions to loyalty — where something that goes against the loyal impulse isn't a betrayal. There are very few options for that. I think, in our culture, you're allowed to be disloyal to your people when they're standing in the way of romantic love, at least when you're a kid. Romeo and Juliet. We buy that stuff. And maybe that's true.

Jill: I wanted to bring up the ending without giving anything away, so I'll just ask: how did you think about the ending?

Levin: I'll just be really general about it. I knew the basic structure of the ending from really early on, years and years ago. In all of my work, what I aim to do in everything, the stories that are coming out next year, and in this novel, is that I want the action to be continually rising, and exploding at the end. The end to me has to be the biggest thing in the book, or in the stories. Everything that has happened prior to the end has to feed the end. That's the way I thought about it, and that's the way I approached it. There are all these balls in the air, and I have to catch them all, and I have to catch them all as spectacularly as possible, in a way that is larger than what has come before.

I spoke to Adam Levin by phone on November 10, 2010.