Justin Cronin is the literary celebrity of the summer. He was the star of this year's book industry convention, he's recently appeared on

Good Morning, America, and he had to go straight from this interview to talk to NPR about his new book,

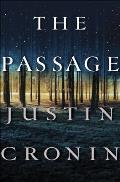

The Passage, an epic, post-apocalyptic novel that's both page-turning and well written.

He's garnered a ton of support from Stephen King, who raved, "Every so often a novel-reader's novel comes along: an enthralling, entertaining story wedded to simple, supple prose, both informed by tremendous imagination....Read this book and the ordinary world disappears." (King also called in to GMA with yet more praise. Watch the video here.)

Before all this, though, Cronin had written two beautiful novels that received far less attention: Mary and O'Neil (which won the PEN/Hemingway Award) and The Summer Guest (which the Houston Chronicle called "a haunting story about the way time changes us and about what endures"). Cronin brings this emotional resonance and his graceful prose to The Passage — a vampire novel, true, and the first in a trilogy, but also, at heart, a story about "a girl who saves the world," at his daughter's request.

Read The Passage for pure summertime entertainment, and be moved and surprised along the way.

÷ ÷ ÷

Jill Owens: You're probably getting tired of telling the story of how you wrote this book for your daughter...

Jill Owens: You're probably getting tired of telling the story of how you wrote this book for your daughter...

Justin Cronin: You can never get sick of telling a charming story about your children!

Jill: I'm sure that a lot of our readers haven't yet heard it.

Cronin: In the fall of 2005 my daughter expressed concern that perhaps my other books were not interesting enough. I said, "Oh, really? Have you read them?" She said, "Well, no. But I can tell." [Laughter] I said, "What should I write about?" She said, "You should write a book about a girl who saves the world, and it should be interesting. And it should have a character with red hair in it." So you don't have to guess what color hair she has!

My heart sank at this because it seemed a little large. But as you know, if you have kids, parenting is mostly pretending you know how to do things you do not. So I said, "Okay, fine, but you have to help me." For about three months, every day after school, when I took my afternoon runs, she came along on her bicycle and we would basically play "Let's Build a Novel" together.

We traded ideas back and forth. It was a version of a game that I've done for many years with creative writing students — who were in college and my daughter was eight. [Laughter] But she's very smart. She reads a lot, and if you read a lot, you know what a story is.

I had no intention of writing this. I was just passing the time with my kid, whose company I enjoy, and maybe introducing her to the family business a little. She had won and continues to win a lot of writing contests. She's a weirdly great reader. She reads two or three books a day.

I have seen her actually bring a book onto the roller coaster for the dull part.

Jill: Wow. She's the hope of the future.

Cronin: She is. All mankind rests upon her shoulders, but she doesn't know it yet.

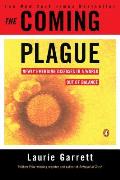

I got home yesterday, and we were driving to a reading. There was just an enormous book sitting on the floor of my wife's car in the passenger seat. I picked it up, and it was a book I read a number of years ago. It's like eight million pages long, and it's very technical. It's called The Coming Plague, by Laurie Garrett. It's a giant book about emerging diseases, emerging viruses. Laurie Garrett is a science writer for the New York Times. I said, "What are you doing with this?" My wife said, "Iris read it. She read it in two days."

I got home yesterday, and we were driving to a reading. There was just an enormous book sitting on the floor of my wife's car in the passenger seat. I picked it up, and it was a book I read a number of years ago. It's like eight million pages long, and it's very technical. It's called The Coming Plague, by Laurie Garrett. It's a giant book about emerging diseases, emerging viruses. Laurie Garrett is a science writer for the New York Times. I said, "What are you doing with this?" My wife said, "Iris read it. She read it in two days."

Anyway, that is the kid who was with me at this point. She was in the third grade, but she read To Kill a Mockingbird in the second grade — which I read in the eighth grade. And, this game is what we did. It was a great game. Every day it got a little better and a little bit richer. In hindsight, I know what was happening, which was that she was bringing out my inner kid in some way, and silencing the inner critics for me.

By the time the weather got cold, and it got too dark too early for her to come along on her bike safely, sometime in December, I decided I would type up an outline and see what I really had. And what I had was The Passage. I wrote a 30-page single-spaced document that was pretty much a description of the book, very close to how it stands now. I thought, Okay. I'll just write a chapter and see how it feels, because unless you have a voice for the book, you don't know how it really is. I wrote the first chapter and I basically never looked back. That's the story.

Jill: It's a great story.

Cronin: I couldn't make it up if I tried. I apparently can make up a lot of stuff, but that one I couldn't.

Jill: I can certainly see Iris's influence in terms of diseases and viruses...

Cronin: Oh, she was totally excited about the prospect of a disease killing all of humanity. She thought that was great. I mean, she is quite young and my book was not for somebody the age that she was at the time. But what was frightening about it was in the abstract, so it wasn't actually frightening. It also taps into kids' natural interest in the macabre. I was like that when I was her age — the scarier the better, even though I was so little that I didn't like being scared, but I wanted to be. That was the nerve we tapped.

Jill: One thing I liked about the book is that it is science and it is the military that unleash this virus and decimate the world, but in the beginning of the book in particular, you bring up ancient statues of vampire-esque creatures, and, in other ways throughout the book, you manage to suggest that this virus and/or vampires have been with us for a very long time.

Cronin: That was a "What if?" position of the book. Every novel has one, I think, particularly one that traffics in a high-volume plot the way that this one does. The "What if?" I came up with while talking to my daughter as I was running eight miles in the Texas heat, was what if all the vampire lore that we experience through books and movies had a biological basis? Most myths are based on something that actually happened. No matter what you believe to be true about all the major narratives and the all major religions of the world, certainly something happened. Vampire stories are ubiquitous and go way back. You can find them encoded in many different cultures, and there are many different kinds of stories. What if the vampire myth had a biological basis?

One of the things that always struck me as very interesting was that if you read the Old Testament, all the major characters lived a really long time. As if in some way, that was a more natural human life span, and it was advantageous to the species to live longer. I am not a geneticist. I am not a scientist of any kind, but I always noticed that and thought it was interesting, and a good idea to play with. These two ideas combined, just simultaneously, hence Project Noah. When I went back to check out Noah, yes, he was one of the guys who really lived a long time. That's one of the original apocalypse stories in Judeo-Christian tradition.

Big stories come out of a collision of things in your head that for some reason or another seem to suggest each other or connect to each other. That was some of the material in which the parts adhered to each other to come up with the plot of The Passage.

Jill: In Laura Miller's review on Salon.com, she points out that your book does have these hints of myths and archetypes and Biblical underpinnings.

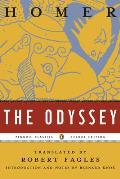

Cronin: Sure. The Odyssey obviously is one; the book has a town called Homer in it. [Laughter] The Passage is full of winks at all kinds of stories and novels and poems and plays. I'm a nerd for books. I'm a nerd for literature. My reading tastes and my reading experience are, you know, every kind, from popular to Shakespeare. There are three Shakespeare plays that are operating in the background of The Passage. And of course, you're not going to write a story about a great odyssey without referring to The Odyssey. If you don't, you still are. So you might as well just wrap your arms around it.

Cronin: Sure. The Odyssey obviously is one; the book has a town called Homer in it. [Laughter] The Passage is full of winks at all kinds of stories and novels and poems and plays. I'm a nerd for books. I'm a nerd for literature. My reading tastes and my reading experience are, you know, every kind, from popular to Shakespeare. There are three Shakespeare plays that are operating in the background of The Passage. And of course, you're not going to write a story about a great odyssey without referring to The Odyssey. If you don't, you still are. So you might as well just wrap your arms around it.

I read T. S. Eliot's "Tradition and the Individual Talent." I don't want to sound like the biggest English nerd in the world, but that made a big impression on me in college.

Jill: He says that all great artists steal, so just come out and acknowledge it.

Cronin: Yes, exactly! What you're doing is always part of something else. Don't forget it. You'll sleep better at night, and you'll know what it is you are actually doing.

Jill: That idea explains the epigraphs in the novel as well.

Cronin: Yes. Every epigraph is from something that was important to me and that also suggested and even lent some kind of thematic coherence and cohesion to the part of the book that it introduces. It's heavy on the Shakespeare. It's actually heavy on the Renaissance in general, but it also has a poem by Louise Gluck, who I happen to really love.  That poem is the "The Red Poppy" from the book The Wild Iris. My wife was a poet at Iowa. We met in graduate school, and when I was there, I was in both the fiction world and the poetry world via her. That was a poem she loved, and our daughter is named Iris. Everything is connected to everything else.

That poem is the "The Red Poppy" from the book The Wild Iris. My wife was a poet at Iowa. We met in graduate school, and when I was there, I was in both the fiction world and the poetry world via her. That was a poem she loved, and our daughter is named Iris. Everything is connected to everything else.

Jill: How did you decide what the vampires would look like and sound like? The throat clicking really creeped me out.

Cronin: That clicking seems very amphibious to me, although maybe I just don't like amphibians. I liked the idea of something that felt like a language, but wasn't. Dolphins do that clicking thing, and we know how smart they are, but their intelligence is so fundamentally different it's just sort of impenetrable to us.

How I decided how they would look is a mixture of traditional vampire tropes in some way. I was giving a nod to the original "What if?" proposition of the book, but also to the idea that these are human beings who are mostly erased. They had lost all but a tiny flicker of themselves. Hence, the buffing away of features. The spontaneous disrobing is the initial gesture of infection — the first thing you do is start taking off your clothes. That's a gesture towards becoming more animal, but also losing your self, all the exterior details that encode your personality. Who you are. Who your friends are. Where you live. All of that stuff slowly is erased from the outside in. All that's left deep within them is one little kernel of something. The story will continue to explore that.

For me, that's the major idea of the whole thing. It's sort of a novel about war and how we regard our enemy. You have to dehumanize your enemy in order to fight a war. So, you give them all kinds of terrible nicknames and you do everything you can to erase from your mind the fact that they're people. It's very hard to have a moral victory in a conflict if you do that. You can have a military victory, but a lot is lost.

I read a lot of George Orwell, and read a lot about George Orwell in college. This was the major idea of most of his later work. I am sounding like the biggest nerd in the world right now, I realize. I'm not really supposed to, but, nevertheless, I'm just going to let it rip. [Laughter]

Jill: I think it will be very appealing to our readers.

Cronin: Of course! Powell's people? We can all be big nerds together.

But you cannot actually achieve a real victory until you understand that your enemies are people. That is one of the things that is happening in The Passage. Amy is the means by which the survivors of the great viral cataclysm can understand and have sympathy and empathy for the virals, those people who are transformed. They give them mercy, which is at the center of that part of the plot. That's what they need to do. These are people who are frozen at the instant before death, hence the desire to go home. If you have ever spent time around somebody who is at the end of their life, that is all they want.

Jill: How did you decide on the thymus gland and its role in the virus? I looked it up today and it makes perfect sense that it comes from the Greek meaning "heart, soul, desire, life."

Cronin: This was a freebie that the universe gave me. I learned about it from a friend of mine who is a writer and an oncologist. He's a poet. We were teaching a conference together. He was talking about a patient of his who had cancer of the thymus. I said, "What's a thymus?" I knew it only as sweetbreads, its culinary version. (Not that I've ever eaten sweetbreads — that's not really me.) He explained it to me. And, among other things, it has a mysterious function that is very complex, which it ceases to perform in adulthood. By the time you hit adolescence, it's pretty much turning off, which makes it very interesting. And its location is perfect. What if the "stake them in the heart" thing really means "shoot them in the thymus"? It was something that could be really particular to their condition.

All the traditional vampire stories are magical stories, stories of a magical being. I didn't want to work with magic. I'm not a magic person. I'm more of a science person. Science is the magic in my life, for sure. My iPhone is exactly what they had on Star Trek, only it's a little cooler. I constantly marvel at and am terrified by scientific and technological achievement. I wanted to ground it in science. When I heard about the thymus gland, it was kind of a eureka moment. It was a marvelous present from the cosmos.

Jill: It does seem absolutely perfect for your purposes.

Cronin: Books are these beautiful accidents. With a lot of the material, you don't know why you deserve this, but you've got it. That was one detail that was incredibly important. It was an accident, and I just bumped into it.

Jill: You were talking about war and The Passage being a war story in some ways. I noticed that, and I also was re-reading The Summer Guest, and there are scenes on the battlefield and from the war there as well. I was wondering what your interest was there, and if you'd ever been in a war?

Jill: You were talking about war and The Passage being a war story in some ways. I noticed that, and I also was re-reading The Summer Guest, and there are scenes on the battlefield and from the war there as well. I was wondering what your interest was there, and if you'd ever been in a war?

Cronin: I think my interest may come from the fact that I have not. I was born in 1962. I missed it. I was too young for Vietnam, and in the '70s and the '80s, nothing happened. For a little while there, the all-volunteer army seemed not to apply. I actually had to register for the draft in 1980, because draft registration (not the draft itself, though) was reinstated following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, oddly enough.

Jill: I didn't know that.

Cronin: Yes. There had been no draft registration for some period of time like '74 to '80. But, then all a sudden, when I turned 18, I had to go down to the post office and register for the draft.

My father also missed the war entirely. He was born in '36. By the time he was done with college and school, he had a wife and one child... or maybe two, me being the second one. I can't remember the timing exactly, but essentially he missed it. There is an astonishing lack of military service in my family. I can go back three or four generations, and I can't find anybody who was in the army.

On my wife's side, everybody was in the army. In fact, when you read The Summer Guest, that injury that Joe has — that is my wife's step-grandfather, essentially. Different battle, different circumstances, identical injury. My wife's father was a Marine. His brothers were all in the military. That is just what they did.

Part of me is contemplating an experience that I simply didn't have, and at some level — not war, but military service — I feel like I missed something. I am 47 years old now. I can't go down and enlist. They wouldn't have me. They would maybe let me hand out sheets and pillowcases, but that's about it. I missed it.

Part of it was the Vietnam war was the war that had just ended when I was a kid. The idea of military service was not a very popular notion at that moment. It was not the best moment for military service in our culture. I came, over time, to learn more about it, to learn more about World War II and Vietnam. I came to see how war is a kind of essential theater in which basic human questions are worked out. It's too bad we have to have it as a way of doing that. But, in the 20th century, that is where a lot of it took place.

That whole generation of men who served in the Second World War was completely transformed. Then they came home, and they pretended that it hadn't happened, a lot of it, a lot of them. But it was clearly a psychological baseline for that entire generation of men. I'm interested in that because I am an outsider to it. I don't know what that says about me, but nevertheless, I keep going back to it. I went back to it in this novel, of course, because we are at war. We are at a different kind of war now, a very open-ended war. It doesn't have a clear, territorial, moral structure like the Second World War.

It is not quite like Vietnam, either. Vietnam was a very territorial war. This is not. We are not trying to take any dirt. But this war is in the background of everything. I started writing The Passage about the time the war in Iraq was really going badly. It seemed to have a crescendo of gore and confusion. That was clearly operating on me when I formulated this story.

Jill: Your first two books are notable for the emotional depth of the characters, but they lead fairly quiet lives, for the most part. In The Passage, that emotional depth is still there, but you have to balance it with a much larger, page-turning, vampire plot. How did you think about balancing those elements in the new book?

Cronin: I ended up just saying to myself: Justin, you write how you write. I didn't have to worry about doing the characterization because I was just going to do it. That's how I do things. I have never made even a secondary character I didn't love and try to flesh out and give a complete humanity. I have an almost systematic way of doing it. When somebody steps on the stage for any important amount of time, I try to figure out who they are. One thing that is a barometer for me is that I ask them what they are not telling anybody. That's my door into who they are. Everybody's got a secret. I've got one. You've got one. We don't have to tell each other what they are.

Jill: Not right now, maybe.

Cronin: Right, we only just met! [Laughter] But I knew that's how I was going to do it because I don't know how to do it differently. But I did strap these characters to this runaway train of a story.

Jill: Sometimes literally.

Cronin: Exactly! At that moment, I thought, "I am actually going to put them on a runaway train." I had always wanted to do that without knowing that's what I wanted to do.

I know how plot and story happen together. That's what I have learned to do as a writer over the last 20 years. I don't think of story and character as separate at all. Plot is separate from character, but story is not separate from character. Plot you can just describe in the abstract. But, what the story actually is, is the intersection of character and event. If you just think of your characters as luggage handlers, people moving the story forward, it won't work. That's not a story I want to read, let alone write.

When I thought of a story, I wasn't thinking about events. I was thinking about people caught up in events of real life or death urgency. Every novel contains scenes of urgency. That's how it happens. Otherwise, it wouldn't be a novel. It wouldn't be a story. What happens has to be story-worthy. I decided that I would put these characters in a situation in which they were essentially all running for their lives all the time. So all of their choices would be life or death choices. They would be the kind that could not be unchosen, could not be taken back. And, it would always strip away the social details. They would be, in a sense, purely themselves because they couldn't avoid it.

I will be super nerd now! There's a wonderful story about Andre Dubus, whose work I love, and I learned a lot from reading him.

I will be super nerd now! There's a wonderful story about Andre Dubus, whose work I love, and I learned a lot from reading him.

This story is slightly apocryphal, but you'll recognize what is real about it. I may have misremembered it over time, but the essential details are there. It's about his accident. Remember, he lost the use of one leg, and lost the other one? The short version is that he came upon a stalled vehicle in the middle of the night driving home from a reading, north of Boston. The people who were driving the car thought that they had hit and killed a motorcyclist. Dubus looked under the car, and indeed there was a motorcycle jammed up under the car, but there was no person. It had been an abandoned motorcycle that they had hit.

He got out from underneath the car, and because of the way the car was positioned, and the way they were standing and the fact that it was night, another vehicle was headed straight toward them. He had no time to make a decision. He only had time to act. And he pushed the woman out of the way and he got hit instead.

And he always said that he did it because he had been in the Marine Corps. He learned to act without thinking. That story always amazes me because you can see him actually working it out in his fiction, later on, and questioning it, and exploring it. Those kind of moments are where real drama lies. Somebody does something without thinking because of what they are.

You can do that with an awkward dinner party. Or you can do it with a plague of monsters. I've written awkward dinner party scenes, and actually, they're very difficult to write. But I chose this time to do the plague of monsters, knowing it was the same thing, just on a bigger canvas and more urgent.

Jill: The way you describe stripping down a character to his or her bare essentials mirrors the idea of the vampires having their humanity buffed away.

Cronin: My God! You're an English major.

Jill: How on earth could you tell? [Laughter]

Cronin: These are the conversations I like having about books, about a story that I've written. Yes, that's exactly right. It's all about things being stripped away to their essence. The basic question of the book is: What does it mean to be a human being? If you're immortal, are you still human? The answer is no. That's what you lose. So it's better to be mortal. The book is basically a fable which says that it's better to be mortal. Without it, the richness of human life is no longer available to you.

Cronin: These are the conversations I like having about books, about a story that I've written. Yes, that's exactly right. It's all about things being stripped away to their essence. The basic question of the book is: What does it mean to be a human being? If you're immortal, are you still human? The answer is no. That's what you lose. So it's better to be mortal. The book is basically a fable which says that it's better to be mortal. Without it, the richness of human life is no longer available to you.

Jill: Dreams figure in very prominently in The Passage. I won't say how, but they're a major plot point. You also write really eloquently about dreams in your previous two books. Why do you like to include dreams as an element in your story telling?

Cronin: There are a couple reasons. One is that I have a crazy dream life. I always have. I think a lot of writers do. A lot of writers and a lot of artists do because what we do for a living very much involves and requires quick and dirty access to the unconscious. We all develop some trick so we can do that. My trick is auto-hypnosis through exercise, which is the healthier version of this. We all know what the unhealthy ones are. [Laughter] I do most of my thinking basically while running or cycling. It has all the earmarks of the auto-hypnotic method. It's rhythmic; it's repetitive. You don't have to pay attention to what you're doing. Your mind floats. It's like listening to the tapping pen. So I think that I write about dreams because when I'm writing, I'm sort of dreaming anyway.

I've always had a crazy dream life. It's very vivid. I remember my dreams. Some of them are great. Some of them are horrible. I was a champion sleepwalker as a teenager, which was one weird thing after another. It was not uncommon for me to wake up and find myself making a peanut butter sandwich, or — this is my favorite one — mangling my desk lamp. I have no idea what it ever did to me.

I spend a certain amount of time thinking about my dreams. I've learned how interesting they are. Your dream life contains a kind of genius of metaphor. You know when you read a metaphor that feels really forced and clunky, and then you read one that feels like the "Hallelujah Chorus"? The first one was made by the conscious mind. The second one was made by the unconscious mind. That ability to put things together that don't seem to go together and yet absolutely do — that's where it lives in your head.

I can give you lots of examples of dreams, but it would be way too embarrassing for both of us. [Laughter] But I've learned to respect that. That's part of my brain that has to light up when I'm writing. I believe that it affects us all every day. You know, there are those people who say, "I never remember my dreams." I want to say, "Yes you do! You do. Stop it. Confess to yourself that you do and then you will."

I like what dreams do. I think they are very much part of my characters' lives, as they are a part of my life. So I give dreams to them. It seems part of a naturalistic presentation of reality and character.

Jill: There is not a lot I can ask about the specifics of plot or character without giving something away. But to me, it seemed like the relationship between Amy and Wolgast is the heart of the whole story.

Cronin: Absolutely. Well, it doesn't surprise me that a father and daughter running around the hot streets of Houston, Texas would come up with a story about a father and daughter. It all goes back to one thing in my life, actually. I can totally pinpoint this. First of all, my daughter and I are very tight. We totally get along. I am the sheriff. I am still the dad, but nevertheless, we really enjoy our time together. I'm intensely sentimental about her, and my son, too. But we're talking about her right now. I'm not leaving him out, but this is what we are talking about.

One of my favorite moments in all of literature, and I say favorite not because I like it, but because it affects me, is a moment in King Lear, which I saw for the first time when I was in high school. I had read the play in class, but I was 17 years old. I was mostly interested in the cute girl sitting one row away. I read the play, and I thought, "That sure is difficult." I didn't understand much about it. It's hard. Then you go see a play by Shakespeare and the actors put life into the voices, and all of a sudden, it's like you can speak Elizabethan English. It makes it available to your sensorium, when they start talking.

One of my favorite moments in all of literature, and I say favorite not because I like it, but because it affects me, is a moment in King Lear, which I saw for the first time when I was in high school. I had read the play in class, but I was 17 years old. I was mostly interested in the cute girl sitting one row away. I read the play, and I thought, "That sure is difficult." I didn't understand much about it. It's hard. Then you go see a play by Shakespeare and the actors put life into the voices, and all of a sudden, it's like you can speak Elizabethan English. It makes it available to your sensorium, when they start talking.

The moment is when Lear comes out on stage with Cordelia, and they've been arrested. She's tried to mount an invasion to recapture the kingdom. The invasion has failed, and Lear, of course, has gone through one humiliating reduction after another. He has finally been arrested, and he is so happy. He's so happy because he has been reunited with his daughter. He's so happy they are going to get to go to jail together. He can't imagine a better destiny for himself at that moment. He says to her we "will sing like birds in a cage." This is a line from the epigraph from Part Two. He basically says, We're going to gossip, we'll tell stories, we'll do each other's hair and nails. He's so excited. And then they hang her.

That moment... I remember watching the play. He comes out on stage holding her body, and he says, "Oh, you are men of stones." That's the line. There is a moment in the book where Doyle says to Wolgast, "Do you think I am made of stone?" (Super nerd here.) The Wolgast-Amy story is very much the Lear-Cordelia story, even though I gave the name Lear to another character. That's the heart of the whole project, because I am a dad.

Jill: Do you have any particular connection with Oregon, since Wolgast has so much affection for it?

Cronin: Here's a weird confession: Oregon is the one state of the Union I have never been to.

Jill: Are you serious?

Cronin: I am absolutely serious. Everything else in the book I know dead cold. I lived in Memphis, I lived in Houston, I actually worked at the little town on the mountain in California where the colony is based. I worked with geography that I knew very well because I've lived a lot of places. But as it turns out, maybe I've changed planes there or something, but otherwise no, I've never been to Oregon.

So it has acquired an almost mythical quality for me, like Oregon is the perfect place. I know that it has these incredibly diverse environments, because of its topography and the way it works. I know it's got every kind of geography present in it, every kind of climate. And it's a place that I haven't managed to get to, so it has mythical status in my mind. Of course, that is where I send Wolgast.

I thought about it later. I thought, "Why did I send him to a place I didn't know?" I had to sit down with a book and I had to figure it out exactly. I realized later on because it was so special; it was like sending him into the forest in a fairy tale.

Jill: Are you going to be disappointed when you come to read at Powell's and you have to face your utopia?

Cronin: I don't know. I hope Oregon lives up to the mythology. It's a pretty tall order, isn't it?

Jill: It sounds like it is, at this point. But it is a pretty amazing state, too.

Cronin: I'm sure I'll love it. I'm sure. [Laughter]

I spoke to Justin Cronin on June 10, 2010. He reads at Powell's City of Books on June 30.