Photo credit: Kateshia Pendergrass

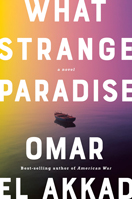

Portland-based writer Omar El Akkad’s latest work,

What Strange Paradise, is a beautiful, angry novel about the migrant crisis in Europe. Expertly teasing out the strings of exile, pride, greed, trauma, longing, and hope that entangle his diverse characters, El Akkad makes clear indictments without sacrificing the complex emotions of the “bad” actors — the smugglers, the Greek islanders struggling with an influx of migrants, the apathetic tourists, a nationalistic and traumatized military. Simultaneously a narrative of hope and a devastating portrait of what is happening in our world, right now,

What Strange Paradise is an example of how fiction at its best does more to explicate and illuminate the challenges we face than any newspaper headline or documentary could accomplish. It is a pleasure to share

What Strange Paradise as

Indiespensable Volume 93.

Rhianna Walton: When

American War came out, one of the things you spoke about was how the novel was born out of your anger about certain global inequalities. I was wondering if similar frustrations inspired you to write

What Strange Paradise.

El Akkad: The short answer is yes, absolutely. The older I get, the quieter my writing gets and the angrier I get writing, which is a strange, disjointed feeling.

With

American War, I was angry at the imposition of exotic motivations and reactions on people who just happened to be on the losing end of a war. A lot of

American War was an attempt to write against that.

I remember a few years back, I was reading a story about a migrant ship that had capsized, and the details were horrific as you would expect. There was outrage. And then the very next day, it was forgotten because there was something else to be outraged about. And I feel like, during the time that I was writing

What Strange Paradise, which basically overlapped with the Trump years, that was our default mode. We had the privilege to instantaneously forget the thing that outraged us today, so we could be outraged by the other thing that came up tomorrow. I genuinely can't tell you anything resembling a comprehensive list of the scandals and outrages of the last four or five years. And in a way, it's a kind of self-defense mechanism, right?

I wanted to write against that as much as possible. I wanted to dwell and keep the camera focused on a single, albeit fictional, case, and to position myself against watching human beings and their misery be forgotten instantaneously.

That's a very rambling way to say, yeah, it also came from a place of anger. [

Laughs]

Indiespensable Volume 93

Indiespensable is Powell's literary fiction subscription club. Click below to discover our newest selection and peruse past volumes.

Learn More »

Rhianna: I can see how, as a writer, being able to take the time to sit in that space and really contend with it would be incredibly rich; but I also wonder more generally about fiction's ability to let the reader do that too, if only because novels take more time and stay in your head longer than a tweet or an article.

El Akkad: I was a journalist for 10 years, so I saw the very short, sharp impact of journalism. I was working in Canada, and I would write an article and maybe the next day it would be mentioned in Parliament. That was always very exciting, but two days later, it's done. Whereas in novel writing in particular, there is no short, sharp spike for most books. Instead, you linger for years, and I don't know which one of those two approaches is more effective. I suspect the short, sharp spike is more effective [

laughs] in getting change made, but in terms of emotional change, of actually altering the emotional worldview of human beings, I feel like that long burn does something to people. Which is why I’ve largely moved into that world.

I'm very much a person who has very bad acceleration, but a very good top speed, and so I need to spend a lot of time with the work before I get to the place where I can say what I want to say. I think novels do that better than any other art form.

Rhianna: You mentioned that as you get older, your writing gets quieter. What did you mean by that?

El Akkad: I think when I was younger, I was... You know, I'm never going to be James Baldwin. Baldwin could take his anger and transform it into something sublime and profound, and that capacity is perhaps the finest talent you can have and I don't think I have that talent. I think for me... You can see the places where it gets away from me, where I'm unable to control that anger and turn it into something much more profound.

When I was younger, that happened a lot more often. And also, it has to do with this idea that every long writing project is in its own way a kind of funeral for the person you used to be. There's something very anachronistic about the production of a novel. Thirty-four year-old Omar wrote

American War and then thirty-six-year-old Omar was out publicizing

American War, and those are two different human beings; and the same thing is happening with

What Strange Paradise. I was who I was when I wrote it, now I'm somebody else, and I like that idea of constant change. I never want to get to a place where there's no sense of movement as a human being.

When I wrote

American War, I had no kids, but when I wrote

What Strange Paradise, I had one kid. Now, I have two. It changes your view of what anger can accomplish, and you start to think a little bit about what the opposite of anger can accomplish — what love and quiet deliberation and meditation can accomplish.

I know I'm a huge hypocrite for saying this, because

American War was a very violent book, but I don't like violence in my media generally. So, the “bang, bang” nature of the work, I think, tends to diminish as I get older. I don't know if that's going to continue. It might be that I hit my forties next year, and suddenly something else happens, but I'm willing to live with that.

Rhianna: I turned 40 this year, and I'm trying to think if I got angrier or more loving. I'm not sure.

[

Laughter]

Given the deeply emotional and political nature of the subject of migration, did you worry at all about the narrative voice tipping into didacticism; or, are we unnecessarily afraid of didacticism in literature? Maybe there’s a place for that.

Hope can be a bit of a drug sometimes when it comes from a place of privilege.

|

El Akkad: When I was very young, we lived in Egypt. I left Egypt when I was five, but that's where I was born. That's where my parents were born, and their grandparents, dating back generations. We are very firmly Egyptian, but my father had to leave because there were no jobs and the political situation was a nightmare. So, I ended up growing up in the Middle East. But when I was very young, we traveled to Paris and London on a summer vacation. And I remember walking around the streets of Paris in particular, and looking at the urban design — there are certain hallmarks of French urban design. Little blue squares with white writing on them that show you the house number on the street, for example.

And I remember looking at these things. And as a kid, obviously, I didn't put it in these terms, but thinking, essentially,

I wonder why the French ripped off our Egyptian modes of urban design. It did not occur to me in the slightest that we were colonized by these people before I was born, and that's how these urban design features ended up on the streets of Cairo where I took them to be ours.

What I'm trying to get at is this idea that political writing is not something that I went out and met. It came to me. I've read a lot of political novels that feel political at the expense of craft or political at the expense of art, but I didn't pick this fight. I had no say in who is showing up to the ring. I just put on the gloves and walked in.

The other side of that is that when we think about the hallmarks of Western creative writing advice, we always come back to the idea of less is more. The Hemingway short sentences, iceberg model where you don't say the thing, you imply the thing. And that's all great and has produced amazing writing, but one of the reasons that somebody like Hemingway could stand on that perch and give that advice and write in that way is because for generations beforehand, the Victorians were doing the shouting on his behalf. There were people who looked exactly like him, who came from the same cultural, ethnic, and religious traditions, and who did the shouting on his behalf such that he could be quiet, safe in the knowledge that people understood exactly what he was being quiet about.

I can't do that because, particularly in this part of the world, stories that resemble mine have not been part of any kind of published literary tradition. There's a famous story of

Edward Said in the ’80s going around to the publishing houses in New York and trying to get the writing of

Naguib Mahfouz translated into English. Mahfouz is the only Arab ever to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. If you want to translate Arabic writing, he's who you start with, and Said was turned down repeatedly. At one point, he asks an editor, "Why?" And the editor says something like, "You know we'd love to, but Arabic is a very controversial language."

And I think about that statement a lot, about what it means for a language to be controversial. So, the way I think about it with regards to how political my writing is, is that I'm not here to be quiet. I am quite happy to be some future generation's Victorians, to be the guy shouting so that they don't have to shout, and they can call their novel

As I Lay Dying, knowing full well that people are going to get the reference because the cultural tradition is firmly established.

I don't think dams break in an orderly fashion, and we are in a situation right now where in terms of literature and art in general, a lot of dams are breaking. A lot of people who haven't had much of a megaphone suddenly do.

I think that criticism [of didacticism] is invalid in a lot of cases, and I don't have a problem right now putting out the kind of work that is susceptible to that criticism. For me, that is a fair trade-off for what I can accomplish in the long term.

Rhianna: I’ve talked with other writers this year who have spoken to the need to write in a way that might feel too explanatory or didactic, because they feel like their stories require extra context for the American reader; and also, about wanting to lay a foundation for others, so that their voices don’t become tokenized.

El Akkad: Just as an example, there's a moment in the beginning of the book where Vänna is pissed off about all the music that's coming from the night club down the shore and she starts explaining what the song is. If you read between the lines, it's basically the song "Big Pimpin'" by JAY-Z, right? Well, so, you go to the end of the novel when the boat is heading towards the island. And at one point, one of the people on the boat says, "Hey, listen. They're playing our music. They're playing ‘Khosara Khosara.’" “Khosara Khosara” is a very popular song from 1950s Egypt, and the beat is sampled on “Big Pimpin'.”

How many readers who pick up this book have a cultural lexicon that includes “Big Pimpin'” and “Khosara Khosara”? Like, there's me. There's maybe two other people on this planet...

So, you're in this situation where if you do take the sort of Hemingway advice and really bury it, well, it was never there to begin with. But if you make it too overt, then it's too obvious. I don't know if the middle line exists for this particular kind of writing, because you either make it invisible, or the second a certain kind of reader sees it, it's too obvious. I don't know what to do about that [

laughs].

Rhianna: One of the distinguishing features of

What Strange Paradise is its multiplicity of voices. What kind of research did you do to prepare for this story, which is about so many different people, places, and personal histories? I'm thinking particularly of the boat, but it really applies to the whole novel.

El Akkad: So, I grew up in Qatar. And the thing about Qatar is that only about 10 percent of the population is Qatari. People come to cash in on the oil production. My school was unlike any environment I've been in since, in the sense that I was surrounded by people from all over the world. And growing up in that environment gives you a certain kind of worldview, I think.

A lot of research for the novel came about same way that it did for

American War, which is from one of my journalistic assignments. I was in Egypt covering the aftermath of the Arab Spring. I was driving around with one of my old high school friends who had come back from Qatar to Egypt, and he was complaining about the price of housing. I asked him, "Well, what's the price of an apartment in your building?" And he said, "Well, the locals' price or the Syrians’ price?"

The Syrians have no choice. They came to Egypt as refugees, and so it's about three times as expensive for them. Egypt and Syria used to be the same country for a while. And for all this nonsense about helping our Arab brothers and sisters that you hear the politicians go on about, the reality on the ground was that these people could be exploited, therefore, they were going to be exploited. And this isn’t just about housing, but applies to the food and vegetable vendor on the street.

The older I get, the quieter my writing gets and the angrier I get writing.

|

A lot of what I saw during that trip influenced the way I was thinking about who ends up on that boat and why. In a previous draft of the novel, I had diary entries from each of the central characters, which I actually liked writing, but it didn't work structurally. So, much like Sarat's diaries in

American War, that stuff never made it into the final cut.

And then the rest was research on the migrant journey across the Mediterranean. Strangely enough, the book that influenced me the most when I was writing

What Strange Paradise is one called

The Wandering Jews, which was written about 100 years ago. And it's about the Jews of Eastern Europe, who were being subjected to horrible mistreatment. Many of them tried to move westward, at which point they were subjected to a different kind of horrible mistreatment. And the details in that book are uncannily similar to the details of every news report that I've ever read about migrants moving through the Middle East and North Africa to Europe. The unchanging nature of that particular brand of cruelty really influenced how I thought about these people.

Actually, much of the dialogue that happens on the boat, in my head happened in Arabic and then I translated it into English, which I think results in a somewhat stilted kind of interaction.

Rhianna: It’s amazing that you were able to do that. I don't know Arabic, so I can't speak to how its cadence might be reflected in the English, but the conversations never felt stilted. They felt ideological and smart and important in a way that maybe isn’t as likely when you're actually in that situation, but also true.

I was curious about how you decided to people the boat. You've got Umm Ibrahim, Kamal, Walid, Mohamed, and Maher, among others. The interplay between their different personalities is fascinating, and almost like a play. How did you determine who would be in those scenes?

El Akkad: It's really fascinating that you would describe it like a play. So much of the book is essentially a reinterpretation of the original stage play of

Peter Pan.

Rhianna: I was in that play!

[

Laughter]

El Akkad: It ranges from the very obvious to the very not-obvious. For example, you have a Captain Hook figure in Kethros, but instead of missing a hand, he's missing a foot. I was also thinking a lot of that movie,

The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover, where everything feels like a stage production. It’s visually very stunning. I was trying to present it in that form.

Of course, like

American War is not a literal depiction of how I think a second civil war would happen,

What Strange Paradise is not a literal depiction of how I think a migrant journey would happen. I tend to move away from that mode. In terms of the character details, I grew up with some of these people in one form or another. Some of them are based on cousins and uncles.

Those are the things that influenced this idea of trying to create a stage play based on a very famous and now comforting story that westerners have been telling their kids for 100 years, even though that story originally comes from a very dark place.

When we think of Peter Pan, we think of the man who refuses to stop acting like a boy. The original impetus for that piece of writing is J. M. Barrie's brother dying in a skating accident when he was young. It's the boy who never got the chance to be a man, and we've inverted it into something very comforting.

And I wanted to take it back, and, for lack of a better term, appropriate it and use it to tell a different kind of story. Those were some of the things that were going through my head when I was putting together the makeup of the boat.

Rhianna: You seem to gravitate toward writing child protagonists. What is it about childhood that feels like the right foundation for the global, humanitarian issues your fiction has focused on?

El Akkad: I'm not sure if I write child characters very well. I should begin by saying that. But for me, childhood feels like our only truly honest interaction with the world. Everything after feels like it's at least somewhat hampered by conceit and obligation, and there's a kind of magical honesty that belongs firmly in the domain of childhood.

I teach a class on resistance fiction, and I talk about how the violence we’re most used to seeing is overt physical violence — bombs, guns, that sort of thing. But holding up this layer are other layers of more passive violence: linguistic violence, the language of euphemism, the language of the passive voice, “collateral damage” instead of "Oops, we bombed a wedding party." And because my writing is so firmly oriented against that kind of duplicity, which allows injustice to ferment, I often veer towards the place where it’s the least likely to show up, which is in childhood.

Rhianna: Several of the advanced reviews for

What Strange Paradise have commented on the straightforwardness of the storyline, but I think the structure of the novel belies that kind of reading. I’m fascinated by it, because how the reader chooses to interpret the ending radically alters how they read the novel and what they take away from it. To me, coming to the ending felt a little like a bait-and-switch in which the frightening but hopeful narrative of Vänna and Amir is revealed as a fantasy, a

Zaytoon.

El Akkad: The very weird thing about this book is that the first four people who read it had four different interpretations of how it ends and what happens.

Without spoiling the ending, almost everything that I think readers need to know about the novel structurally is on the epigraph page. But I have been fascinated by the number of people who have superimposed their worldview onto the narrative, and I don't mean that in a critical way. It's a source of great joy for me, because I think that is the point of engaging with literature. What you feel has happened [

laughs] is what matters. What I intended does not matter at all.

The main difference between

American War and

What Strange Paradise is that

American War was overtly a very structurally polyphonic thing. There were source documents, and there was movement in time and place. In this novel, most everything is from the same neighborhood. It's very quiet, and sort of under the surface.

Structurally, I was trying very much to write a Biblical kind of story that alternates between an exodus from Egypt and a miraculous rebirth. That’s not particularly original on my part, right? [

Laughs] I was trying to follow one of the oldest stories ever told. There isn't much in the way of overt stylistic experimentation here.

I don't think a lot of the advanced reviews were wrong. It does feel like a much quieter book [than

American War]. I was just trying to do something else, and I hope that the thing I was trying to do resonates. But I can fully understand picking up

American War, which is twice as long and is a real kitchen sink book in terms of the number of things going on, and then picking up this book where it's… I don't know if it's simpler, but I do think it's quieter.

Childhood feels like our only truly honest interaction with the world.

|

Rhianna: I don't think it's simple. One of the things the structure does is serve as a metaphor for the kind of magical thinking that the reader engages in. And that a lot of the characters engage in, although their magical thinking is all over the map. You've got Kethros, whose magical thinking is that he's reimagining these migrants as colonizers. And you have the migrants’ need to reimagine the West as a place that's actually going to be open to them. And then you have the readers’ need to believe that a teenage girl and a little boy are going to outwit this horrible mechanism of displacement and dehumanization.

I felt a little indicted as a reader, that I wanted that fantasy to be real, but I don’t think the novel can ultimately be read that way.

El Akkad: Yeah, thank you. I mean that's as close, I think, as anyone’s reading has come to what I intended.

And what's been really interesting… the way you phrase that is absolutely correct or at least resonant with my experience, in that, with a lot of early readers, their magical thinking won.

It won in a way that's sort of alarming, but also kind of comforting. It's alarming in the sense that I think hope can be a bit of a drug sometimes when it comes from a place of privilege, where you can simply assume that everything's going to work out because everything must work out. But it’s comforting that there is an aspect of that in human nature.

There have been many cases where what I intended to be, as you put it, an indictment of our selective outrage, our temporary outrage, and our essential hopefulness-above-actual-solutions culture, has been defeated [

laughs] by our hopefulness-above-all-else culture.

That's not a good or a bad thing. It's just fascinating for me to see as a reaction to the book, because there's a mode of reading or consuming this kind of work that comes from a place of deep anger.

Rhianna: Masculine weakness — identifying it, fearing it — runs through the novel. Whether it’s the conflict between Loud Uncle and Quiet Uncle, or Umm Ibrahim and Walid, or the tension between Vänna’s parents, or Kethros and pretty much any man who isn’t him… I’m interested in its appearance in the novel, and about how you understand the role masculinity plays in something like the migrant crisis.

El Akkad: So, almost exactly 11 years ago, my father passed away quite suddenly. He was on vacation with my mother in Italy and he suffered a heart attack. He was 56.

I’m an only child. I've never been close with my extended family; I had to learn in one night that half my family was gone. It was devastating [to lose] the only man who I thought of as a guide for how to be in the world. So, I flew over to Italy. We had to repatriate the body, because my father wanted to be buried in Egypt. It was a real mess.

During that whole period of this very intense ugliness, I did not cry once. I had grown up in a tradition where men don't do that kind of thing, with a crystal-clear interpretation of what it means to be a man. And it was a ruinous interpretation, because to this day, I have pieces of emotional scar tissue that if I get anywhere near them, I become instantaneously broken, which is a horrible way to be in the world.

I was thinking about that in the context of agency. There's a line in the book where one of the characters talks about his father telling him that a man is the sum of the demands he makes of the world, and that there is essentially no weaker form of man than one who makes no demands of the world.

It doesn't matter if they succeed in getting those demands met. It's the man who makes no demands of the world who is the weakest sort of man, which is my all encompassing general definition of what toxic masculinity is. You must constantly be demanding of the world, and anything else is weakness.

And so, the men who must leave their lives behind, hop on a rickety boat, and go start from zero are being put in a position where not only are they not allowed to make any demands of the world, not only is their agency in that sense reduced to zero, it's actually reduced to less than zero. Now they must beg of the world just to exist.

I think a lot of the toxicity that comes out of these men is prompted by knowing deep down that they've been put in a position of making negative demands of the world, where they are begging the world for scraps. And it makes them violent and ugly in a way that certainly resonated with me, as someone who was brought up in that environment. The times when I've become ugly have had to do with the emotional residue of being brought up in that sort of world.

Trying to rid myself of that interpretation of what it means to be a man has been a very difficult and long process. And I think a lot of the guys in the book are in the process of being consumed by that interpretation of masculinity.

Rhianna: Thank you for that beautiful answer.

One of the issues

What Strange Paradise brings to the fore is the economics of migration, and the amorality of people like Mohammed who profit off of other people’s desperation. Mohammed’s especially interesting; he’s very smart and has a lot of philosophical justifications for his actions like “Conscience, brother, is the enemy of survival” and "This is about business. It's not race," but I wasn’t convinced. That said I’m very privileged to be here and able to make that indictment; are you at all persuaded by his arguments?

El Akkad: Not in the slightest.

[

Laughter]

I disagree with the vast majority of what my characters have to say. The part where Mohammed says, "This is about business. It's not race," is so obviously contradicted by the reality of the situation, where everybody with darker skin is ushered into the bottom of the boat where they are far more likely to drown if anything goes wrong.

I think back to this idea of the different languages of violence, and one of them is very much an economic language. And this to me is one of the things that I will never, ever convince anybody of, but

American War was not a novel about America. It was set in America, but it was trying to tell a different kind of story.

What Strange Paradise, which is set on the other side of the planet, is very much an American novel.

One of the central pillars of economic power-wielding in America has been to do with money what it could no longer do with overtly racist policy. So, you get to issues like redlining or housing covenants — you're using money to do what you can no longer do with chains.

I was thinking of that in the case of the migrant passage, where the economic structure is doing the heavy lifting, and how much of a camouflage that is for the people doing this violence to be able to say, "It's just business" and kind of wipe their consciences clear as a result.

The details of the economic side of this passage are actually one of the few places in the book where it hews very closely to the reality of the trade.

Rhianna: There’s a prehistoric beast on the island that severs birds' wings. It's rich with metaphorical significance, but also an unusual flight of fancy for a novel that is otherwise quite realistic. What’s with the giant lizard?

[

Laughter]

El Akkad: There are certain places where my interests as a writer intersect and result in some pretty bizarre creations. There’s the crocodile in

Peter Pan, but it also comes up in the context of the overriding fantasy. None of the flora or fauna on the island is real. When I got the PDF back from the editors, there were all these comments and questions saying, "Hey, I looked this up on Google. It doesn't seem to exist. Are you sure it's real?” So, it’s an intersection of those things, but it's also an intersection of my thinking about climate change as it relates to fiction.

American War was an overtly cli-fi book, but the way I've been thinking about climate and fiction more recently has been, again, a much quieter kind of thinking. I don't think cli-fi as a genre is going to exist in this form for much longer. I think it's going to be impossible to write any kind of novel in the coming years and not have to contend with the fact that our earth is changing all around us. I was thinking about the way this is going to impact the life cycles of these different creatures.

It was the intersection of the references to

Peter Pan, my imagining of the fantastical beasts who have populated this island, and my thinking about what climate change is going to do to the living conditions of every living thing on this planet. And out of that car crash of three entirely different modes of thinking comes this strange little beast that confuses the hell out of readers.

I spoke with Omar El Akkad by Zoom on June 15, 2021.

÷ ÷ ÷

Omar El Akkad is an author and a journalist. He has reported from Afghanistan, Guantánamo Bay, and many other locations around the world. His work earned Canada’s National Newspaper Award for Investigative Journalism and the Goff Penny Award for young journalists. His writing has appeared in

The Guardian,

Le Monde,

Guernica,

GQ, and many other newspapers and magazines. His debut novel,

American War, is an international bestseller and has been translated into 13 languages. It won the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association Award, the Oregon Book Award for Fiction, and the Kobo Emerging Writer Prize, and has been nominated for more than 10 other awards. It was listed as one of the best books of the year by

The New York Times,

The Washington Post,

GQ, NPR, and

Esquire, and was selected by the BBC as one of 100 Novels That Shaped Our World.

What Strange Paradise is his latest book.