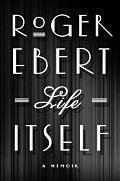

Roger Ebert, beloved film critic, writer, and, these days, social-media maven, has written a beautiful and moving memoir in

Life Itself.

Publishers Weekly, in a starred review, described it as "reminiscences both witty and passionate from one of our most important cultural voices." Beginning with his first memories, moving through his career in journalism and film criticism (including chapters on specific directors, actors, and friends), and ending with a candid discussion of his cancer, his marriage, and his life now,

Life Itself is an honest, funny, impressionistic journey through a fascinating and dramatic life.

÷ ÷ ÷

Jill Owens: You write at the beginning of Life Itself that your memory has become more accessible to you since your illness, that you "live more in your memory and [have] discover[ed] that a great many things are safely stored away." But you truly do seem to have an amazing capacity for recall, even of specific conversations that happened many years ago. Do you think this ability was shaped or honed at all because of your career in journalism and as a film critic?

Roger Ebert: I believe that the act of writing in itself activates memory centers, so this may be true. I lost much time as a teenage sportswriter waiting for inspiration to strike, until a fellow writer, all of a year older, lectured me, "The Muse strikes during the act of writing, not before."

Jill: How did you decide to structure the memoir in this way, focusing on specific subjects in every chapter rather than strict chronology?

Ebert: No life is a chronology to the person living it. In memory, it becomes translated into touchstones. This was a way to avoid having everything seem to appear as a jumble.

Jill: How long did it take you to write Life Itself?

Ebert: It became clear to me early that in writing my blog I was being drawn to autobiography. I began to consciously structure some entries on that basis. Then, in August 2010, I repaired to the woods in Michigan and spent about five weeks full time. I continued to write through January 2011.

Jill: How did you think about writing the prose of the book on a sentence level, and was that in a different way than your blog or your other writing?

Ebert: At this point most of what I write is in the same voice.

Jill: There's wonderful humor in the book, too. How much did you think about tone, and how did you decide to tell so many stories and anecdotes about your friends?

Ebert: Well, my life with friends has often centered around the celebration of anecdotes. I'm an incurable storyteller, perhaps to a fault. I think evoking a moment in an anecdote is more fun that simply recounting it.

Ebert: Well, my life with friends has often centered around the celebration of anecdotes. I'm an incurable storyteller, perhaps to a fault. I think evoking a moment in an anecdote is more fun that simply recounting it.

Jill: You write movingly of your rituals in various places. When and how did you become consciously aware that creating and participating in them was a way of celebrating the continuity of life?

Ebert: Early on. I've always been aware of floating on the current of time. In the autumn of 1964, as I prepared to leave my Illinois home town for a year in Cape Town, I began sort of a ritualistic farewell. That pattern has persisted.

Jill: What do you enjoy most about writing for your blog and for social media? (I think almost everyone I know follows you on Twitter, by the way.)

Ebert: It keeps me in touch. For me, without the power of speech, it truly is a social media. Like all journalists, I've always been fascinated by "what's new," and I love to share stuff. The 140-character limit is an interesting discipline. I decided at the start to stay away from weird Internet spelling, and write in ordinary English.

Jill: At one point, you write, "So much of what happens by chance forms your life," which is undeniably true for everyone, yet you seem more aware of it than many people. It's a humbling view of the creation of a person's life over time. What do you think made that apparent to you?

Ebert: When I review my career, I realize how unplanned it was. I fell into newspapers. I became seriously involved in reading because my first college professor became a lifelong mentor. I ended up at the Sun-Times by chance. The TV show wasn't my idea. These things happened to me, not because of me.

Jill: You describe your relationship with Gene Siskel as sibling-like and as one of the most important in your life, but the two of you were also frequently feuding. What was a disagreement you had with him that you remember most?

Ebert: We had a shouting match over the meaning of a coin toss that was both ridiculous and very angry. It seemed to me that I had won, and to him that I had lost, because we differed over why we were flipping.

Jill: Your approach to reviewing was taken in part from Pauline Kael and Robert Warshow, and you write that Warshow thought, "[T]he critic has to set aside theory and ideology, theology and politics, and open himself to...the immediate experience." You wrote about what happened to you, while watching a movie. There's an authenticity to that which impresses me deeply. Can you talk a bit about how that approach worked for you over the years?

Ebert: If you describe your own experience, that is inarguable. If you impose theory on it, it takes your feelings to one remove. Sometimes I find myself trying to explain why I liked a "bad" film. I received enormous heat for praising a movie named Knowing. But it had such an impact on me, and I had to say so.

Jill: Who are some of your favorite film critics writing now?

Ebert: The remarkable Stanley Kauffmann is still writing occasionally at the New Republic, in his 90s. There are too many really terrific young critics to single out only a few. The Internet has permitted a golden age of film criticism, and there is more valuable work being published now than ever before. Pauline Kael would have been a natural blogger.

Jill: You write that your secret as an interviewer was that you were impressed by the people that you interviewed, that you were "beneath everything else a fan." (I find the same thing, in interviewing authors.) How did that influence your technique?

Ebert: I listened. I was not the authority. I preferred not to ask formal questions but, when I was allowed to, observe my subject engaged in something while I watched and listened.

Jill: You write at one point that you wouldn't have made a competent academic. Why is that? Is it related to your distrust of deconstruction that comes up elsewhere in the book (particularly in relation to literature)?

Ebert: Yes. I prefer "appreciation" more than theory. Analysis of "the immediate experience" and discussion of how and why it happens.

Jill: I love Russ Meyer's description of what the two of you were trying to make with Beyond the Valley of the Dolls:

The movie...should simultaneously be a satire, a serious melodrama, a rock musical, a violent exploitation picture, a skin flick, and a moralistic exposé of what the opening crawl called "the oft-times nightmarish world of Show Business."

What was the strangest or most surprising thing about that whole process?

Ebert: That we were given free rein by 20th Century-Fox, which was in a financial hole at the time, and that Russ was completely open to my most bizarre notions, as when I informed him late in the writing that I had decided our leading man was a lady.

Jill: What are some of your favorite shots, or scenes, in movies?

Ebert: Mr. Bernstein in Citizen Kane, telling the story of the girl on the ferry boat with the parasol. There is so much in what he says that reflects my own view of time and life.

Jill: You write convincingly about why you prefer black and white in movies to color. Could you share some of that with our readers?

Ebert: It is more pure and dreamlike. More stylized and less real. Made of composition and movement, unaffected by the inevitable emotional loads of color. More timeless.

Jill: How much do you think your early childhood experiences, like Catholicism, shaped your aesthetic taste in films and literature?

Ebert: Enormously. Pauline once observed that the best newer American directors (she named Coppola, Scorsese, and Altman) were shaped by the pre-Vatican II church. The ceremony, the incense, the symbolism, the parables, the discussions in religion classes ? those were important shapers of my thinking.

Jill: The chapter on Scorsese is fascinating, because your lives had so many parallels, and because you credit him, in part, with transforming you into an actual film critic (as opposed to just someone writing movie reviews). Can you describe that process, or moment?

Ebert: We talked a lot in the 1960s, after I wrote the first review he ever received. It was nothing he said in particular, but how he spoke about films in general: in voluptuous specifics.

Jill: Your chapter on Werner Herzog was my favorite in the book. You write, "He is in the medieval sense a mystic" and "Artists like [him] bring meaning to my life, which has been devoted in such large part to films of worthlessness." Can you elaborate a bit about your personal and aesthetic connections with him? And do you have a favorite movie of his?

Ebert: A favorite? Very difficult. Perhaps Fitzcarraldo, because it embodies his own approach to his art. I admire his fearlessness, his absolute openness to subject matter, his viewpoint both loving and dubious of humanity, the way his style seems to unfold naturally from each film. Most of all, I respond to his embrace of big themes.

Jill: Some of the most moving passages in the book are about your wife, Chaz, to whom the book is also dedicated. What did she think of Life Itself?

Ebert: Simply put, she likes it.

Jill: What books are you reading and enjoying lately?

Ebert: Midnight in Paris [the new Woody Allen film] sent me back to re-read A Moveable Feast and The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. Then I returned for the third time to Henry James's The Ambassadors, which I now think is probably his greatest novel. Now I'm buried again in the indispensable Dickens ? Little Dorrit, followed by Bleak House.

Jill: Towards the end of the book, you write about not being able to eat, drink, or speak any more, and missing primarily the conversation and community that surrounds meals. You write, "Maybe that's why writing has become so important to me. You don't realize it, but we're at dinner right now." I wanted to thank you, then, for sharing a wonderful meal.

I conducted this interview by email with Roger Ebert, shortly after he returned from the Toronto Film Festival. I was pleased to find this note attached with his responses: "Dear friend: These questions did not arrive to me with your name attached, but I must say I've received a lot of email questions now at publication time, and yours are by far the most appreciated."