In January 2004, a week before

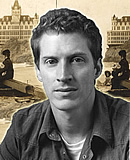

Andrew Sean Greer's second novel arrived in stores,

John Updike told

New Yorker readers, "

The Confessions of Max Tivoli is enchanting, in the perfumed, dandified style of disenchantment brought to grandeur by

Proust and

Nabokov."

More raves followed, from BookPage ("strikingly original and beautifully told") to Kirkus ("old-fashioned narrative fun in a literary hall of mirrors"), from Elle ("[a] deft, new modern master") to Esquire ("an astonishment"). The Today show pegged Max for its book club. The novel camped on bestseller lists nationwide.

Born with the mind of a normal, healthy baby and the body of a dying, old man, in September of 1871 Max Tivoli "burst into the world as if from the other end of life." Max writes,

The days since then have been ones of physical reversion, of erasing the wrinkles around my eyes, darkening the white and then the gray in my hair, bringing younger muscles to my arms and dew to my skin, growing tall and then shrinking into the hairless, harmless boy who scrawls this pale confession.

Six decades after his birth, a twelve-year-old boy sits alone in a sandbox, scribbling unbelievable biography: "There is a dead body to explain. A woman three times loved. A friend betrayed. And a boy long sought for."

Fulfilling the great promise offered by Greer's acclaimed stories (How It Was for Me) and sparkling first novel (The Path of Minor Planets), Max Tivoli is at once a love story, a mystery, a lush Victorian adventure, and literature dressed as science fiction, a wonder with wide and deep appeal.

Dave: Do you feel differently about Max Tivoli now than you did when it was first published in hardcover? So much has happened: the Updike review, the Today show selection? Has your vision of it changed?

Andrew Sean Greer: When I was first interviewed about Max, I would talk about it as a historical novel. I talked about all the research I did. That seemed to be what interested people. Now when I talk about it, that doesn't come up at all. I think I have a better understanding of what actually attracted people to it. I had no idea at the time.

My great fear was that the first review would come out, and it would say, "What an overwritten piece of hokey, old-fashioned writing." I thought, It's supposed to be that, but maybe people won't enjoy it, so I'll sell it as a piece of research. In fact, people are not interested in the research and thank god, because I'm not a very good researcher.

Readers are interested in the old-fashioned, philosophical parts that are harder to talk about. That surprised me. I hadn't sold it to myself that way. I had thought, I'm going to write a story in a voice that interests me, and I'm not going to think about what it means. Then I'm called to talk about exactly that.

Dave: I'm assuming it's true that your initial inspiration was the Bob Dylan song ["My Back Pages"]?

Greer: That's not made up, though my friends joke with me; they hear me say it so often at readings that they now assume it is.

I had the idea singing that one line, I was so much older then / I'm younger than that now, and I wrote it down. I didn't come back to it for a couple months because I was in the middle of a book.

It seemed at first like a bad idea, but when I came back to it and realized I had to write another book I was able to see what would be interesting to me about it, which wasn't the science fiction idea of someone aging backwards but ideas related to second chances at love. And I could write about being different inside from the way you're perceived on the outside. Also, I realized I could set it in a historical context, which was the terrifying part, really, not the aging backwards part.

It's often hard for me to remember how it started out. I'm told that early drafts were incredibly different from the book that exists now, but I don't remember. You start to think you just sat down and wrote the book, which I know is not true.

Dave: It struck me that Dylan must not be satisfied having his songs covered by thousands of musicians. No, now he's moved on to spawning novels.

Greer: And I don't even know any more lyrics to that song! My dad was a huge Bob Dylan fan and played him all through my youth, but I can't say I've listened to him since high school. But there it came.

Dave: The backwards-aging gave you the novel's basic structure, but Adrienne Miller's review made me think of a different kind of structure: the uncooperative structure of our lives. She called the book "a meditation on the body as a stranger, a betrayer." We can't grow up fast enough when we're kids, but soon enough we want to slow time down.

Greer: A lot of the characters are struggling to break out of whatever they've been given. Sometimes they should just accept it, like Max, but they're at a time in history where everyone is trying to change and reinvent themselves. They're taking part in that, mostly without success.

There's the part in the book where the bear in the carnival gets slaughtered. Readers will come up to me and say, "Why did you put that in the book? It has nothing to do with the plot and it's just horrible to read." I'm not able to answer them very clearly. All I can say is, first, it really happened, and it struck me, so I put it in. But I cut hundreds of pages out of the book of stuff that really happened, and I kept that passage in.

It was something about being accepted for a while if you're amusing enough, and then, once you're not useful anymore, you're just taken down. You have to be in control of your destiny. All the characters are aware of that.

Dave: Max calls himself a "monster" several times. I couldn't help equating him with the bear in those passages. They're both outsiders. Max manages to hide it, but he never forgets that he's different.

Then in terms of the use of that word, "monster," there's a passage near the end of the second section where he writes, "You cannot hide. I will always recognize you, Alice. I will always find your hiding places, darling. Don't you know that perfume gives you away?"

Kind of creepy.

Greer: It is a little creepy. In earlier drafts, he was even creepier. I had wanted him to be a little disturbing, for you to be on his side when he's really an incredibly selfish person, but I pulled that back a little.

I was thinking of books like The Invisible Man and Dorian Gray and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, where the protagonist, for whatever magical reason, is selfishly attracted to his deformity and becomes a sort of monster. Max isn't so much that, but he does get deformed by it. It has nothing to do with aging backwards, exactly; he chooses it himself.

A lot of readers have found him unlikable. I sort of meant him to be.

Dave: He does say a few times, "Don't feel sorry for me." I don't know how seriously we're supposed to take him, but some of the things he does really do stand in the way of making us sympathize.

Greer: He really is trying to seduce, and to forgive himself, even though he claims just to be confessing.

In some translations, they've changed the title from "Confessions" because it sounds too much like The Confessions of Saint Augustine. In Catholic countries, it sends readers in the wrong direction; they would expect some kind of change and miracle, a saint-like state at the end. They've changed it to The Incredible Adventures of Max Tivoli, or something like that. I was fascinated. I had no idea that would be lying in wait for me.

Dave: I just saw a copy of the book in Italian, actually.

Greer: It's incredible, these translations. I can't explain what it was like to get the Chinese version. You can be prepared, but then you open it up and realize, It really is in Chinese. I can't read any of it.

Dave: You mentioned the historical aspects earlier. Certainly San Francisco plays a major role in the story. It's like a giant set piece. The three-penny planks on Fillmore Street? You seemed to be enjoying yourself, piling on the description.

Greer: I did. I had to pull it back a bit. It's so tempting, when you do research this is probably the high school student's problem, still you want to put all of it in, just to prove you know it. It turns out to be better to put just some in, so people think you know even more.

It was fun. It was very hard for me, too. I'm not a journalist at all, so I was bound to get things wrong and I did, as my Spanish translator pointed out to me in long emails. She was a much better researcher, and she found all of the mistakes.

I wanted Max to feel like someone who is very aware of the world and someone who takes a certain pleasure in describing it. It's a sad novel, but there would be a kind of beauty to it because it would be decorated in that way.

I was fascinated by the details that I'd never heard before, the ones that are lost forever, like a three-penny plank. I wanted to mention them without explanation so it wouldn't be like a historical novel where you're learning anything. Because a three-penny plank? Did it cost three pennies? I don't even know what that means. That seems like a lot of money for a plank in those days.

I would try to use these details so the voice would sound like it was coming from someone who lived within the age, and you would realize how many of the details that were taken for granted are absolutely lost.

Dave: There's a great scene where Max overhears Hughie and Alice naming things that are gone forever.

Greer: I point directly at that, don't I? It was interesting that I let myself do it. I think I had realized it was a theme throughout.

It's fun when you talk with your friends about things like the pull-tab on a can of soda, which I barely remember. You would find those little pull-tabs scattered everywhere on the ground at the pool, I guess from beer cans. Those are gone forever, for better or worse. Or the little plastic thing in the middle of a 45 record. Alice and Hughie would feel the same way. And it would be alienating for us to hear these strange creatures who cared so much about the way a wet, wool bathing suit smelled.

Dave: A line that I'd underlined in The Path of Minor Planets, which I read before Max Tivoli, describes Denise aging to discover "your twenties choked with flowering vines; your thirties thinned to only what you tended. People disappeared, and events, and opportunity."

I came back to that line, thinking of Max, perpetually at odds with people moving on a different life track than he is. Alice is the book's free spirit, but she's still following a fairly traditional aging pattern. Max is completely alien to the process. He's able to look at it and see people on a kind of conveyor belt.

Greer: It's so strange to hear you quote Path of Minor Planets back to me. I haven't read it in a while or made myself connect them. I guess you're right. In some ways, he's free of it, but he's envious, I guess, of the ease with which people could just float along.

Dave: Max's envy reveals itself, for example, in his deepening physical attraction to Alice as she ages.

Greer: I wanted to explore this sense we have that if you were to age backwards it would be fantastic, how wonderful and crazy it would be to be beautiful when you were older and you had all this wisdom. It turns out something about the aging process has nothing to do with that.

I thought that Max would be attracted to a woman like that, attracted to her aging and what it would mean, counter to your expectations. He would gain nothing from getting younger because he isn't interested in those young women on the street. He's doubly cursed because he's seen enough of the world and he isn't superficial enough to enjoy his body.

Now it seems sort of depressing, the idea that Alice is just on a conveyor belt with everyone else. I guess so. She does end up being a mother figure in a small town with a fairly conventional life.

Dave: I don't mean to darken your closing.

Greer: But I wanted her to have a happy ending!

Dave: That's another thing. You talked about Max being selfish. Maybe this is a problem for you as the author because you're tied to the basic premise of the book Max is writing his confessions but leaving this document for Alice seems damn near heartless. How incredibly heartbroken is she going to be when she finds it?

Greer: I know. It's awful, not only to live this life but then to brag about it almost, to have yet another way to appear in Alice's life.

Dave: A fourth time.

Greer: Yes, one more time. It's sort of why I added a postscript saying that it wasn't found until much later. In my mind, I was thinking, Alice won't know about it for a long time or perhaps ever. But Max's son will know about it and forgive him by allowing it to be published. That's just my little idea at the end to redeem it.

But it is true: To love someone in that kind of immature, obsessive way is a destructive act. It demands so much of that person. First, that they just listen to you for so long and pay attention. It warps their life as well. And maybe that's me going back to my younger self and admonishing myself for expecting so much from other people or from that emotional state.

Dave: In The Path of Minor Planets and the stories in How It Was for Me, particularly "Life Is over There," the time continuum often comes unhinged. A line or a short passage will give us a brief vision of the character's perspective years down the road. The narrative comes out of its linear frame to approach the same event from a different perspective.

Greer: That happens a lot in the stories and in Path of Minor Planets. In Max, too for instance, when he first gets together with the widow Levy he talks about her funeral and then the first time he kissed her and now when he's a child, all together.

I almost removed those parts from Path of Minor Planets because I worried it was too distracting. For some reason, it made the story much more interesting to me.

As a kid, it was hard for me to get it through my head that when you would meet someone like a grandmother she hadn't been born sixty or seventy; she'd had this whole other experience; she might even consider herself to be thirty-eight still and would be surprised looking in the mirror to see what you see. Or that she was going to be something else entirely later on. I could never get that through my head. Maybe I still can't, which is why I make my characters age in a paragraph or two just to see what they turn into. Maybe that was the whole experiment with Max, to do it in reverse and see what he would become.

Dave: I was surprised to discover that you really did pretend to be a boy's tutor, as the character does in "Cannibal Kings." It made me wonder how you approach autobiography in fiction, or what you think of it.

Greer: That's one of the few truly autobiographical things I've ever written, and it's one of the strangest.

Dave: How did you get hired to pretend to be someone's tutor?

Greer: It's almost literally like that story. My friend was someone's English tutor. The boy's parents ran a Korean grocery. They had saved enough money and they wanted him to make it in the world, but they worked constantly and had no time to take him on a tour of boarding schools. My friend was meant to do it. She couldn't make it, so she said, "Why don't you take him and pretend to be the tutor?"

I think I was twenty-three, when things like that still seemed possible. Someone needed that money. If my friend wasn't going to make it, someone she knew should. This was in New York, not Seattle, like it is in the book. I know I wasn't twenty-five yet because you couldn't rent a car until you were twenty-five in New York; you had to go Rhode Island. So we took take a train to Rhode Island to rent a car.

He was the weirdest kid. And I really did have to sit in interviews and pretend I knew him well. I did not know him at all. It was crazy. And it was during a huge blizzard. It was one of the strangest things I ever did, but I made some money.

Dave: And you got a story out of it.

Greer: Yes. More than novels, when I'm sitting down trying to think of a short story, I'll sometimes think, What is the anecdote that I tell at a dinner party that always works? Because that could be a story; I already have a structure for it. I'll just change it however I see fit, as if I really were able, at the dinner party, to make the story whatever I wanted. If I were a true liar, which I'm not in real life, what would I do?

The stories are often like that; the novels, not so much, because you don't actually tell a story for three days. In How It Was for Me, a lot of the stories are autobiographical in some way.

There's one ["The Art of Eating"] about a woman who works as a food taster. My boyfriend's mom had been living with us for months and months. He was traveling a lot, so she and I were there together in the house all the time. I just started writing about her.

It's not really her, but like the woman in the story she was looking for positions. I'm not sure food taster was one of them, but it seemed like that kind of deal was being offered to her in exchange for housing all the time. She's nothing like that character, but that's what I had around, and that's where it started.

Dave: Does being an identical twin influence your storytelling or your perspective, do you think? It would seem that at the very beginning, you were handed a peculiar platform from which to view your place in the world.

Greer: And how do you think that would change me? I'm curious. I want psychoanalysis from you.

Dave: I have no idea. Maybe you'd have a skewed self-awareness? Probably every child wonders at some point whether everyone else is as important as you are. Does the world revolve around me? But there was always another you out there.

Did you read A. M. Homes's essay in the New Yorker ["The Mistress's Daughter"; Dec. 20, 2004] about meeting her biological parents for the first time? She's adopted.

Greer: I didn't read that.

Dave: It was fascinating, and unsettling in the way a lot of her writing can be. She's thirty-one when the mother contacts her for the first time. Very quickly, she discovers how different her life might have been had she grown up with these people, who couldn't have had less in common with her adoptive parents.

The biological father wants to get DNA tests just to be sure. They're in the waiting room at the lab when her father stands up and she recognizes her ass on him.

Greer: Oh, my God!

Dave: Right. And she knows at that point that it's him. It can't not be him. She's convinced. She goes through with the test just to please him.

Greer: It's hard to know how it affects my perspective because it's the only one I have. I don't know what other people's experience is.

The one thing I have noticed, my brother and I both, is that we're used to strangers coming up to us and thinking they know who we are. Even after they hear that we're not this other person, they still feel like they know us, and they'll tell us very intimate things. As if, even knowing that I'm a total stranger, I'm enough like my brother that they will actually feel a connection to me. We don't find it odd at all to meet people and very quickly learn things about them.

I'm told that I write about people being incredibly lonely. There's also that. I'm used to having this other person around all the time with whom I feel a real connection, and there were large parts of my life, certainly, where that person was gone. I had to figure out how to be alone.

As for storytelling, I started out making little plays for him when I was very small, and he did the same. I was writing them for him, in a way. I used to show him absolutely everything because he would always approve. He was always amused. He doesn't have any sort of barrier to it.

Dave: A pair of identical twins lived down the street from me, growing up. They were in my grade. Pretty typical stuff, but I lived near them for years and I still couldn't tell them apart when they wanted to pass for each other.

Greer: There's also that: shifting identity, reinvention. You get to see yourself if you had taken a different life. Like A. M. Homes.

Even though we ended up not taking very different lives they're really very identical still I get to see what I would look like with a different haircut without having to get the haircut. Or, What if I wore red all the time, like he does? What would that look like? Or if I lived in Brooklyn and had these friends and took up smoking and quit smoking, without having to do it? The two of us think of ourselves as very different, but other people would be struck by how similar every gesture is.

I would buy that. A lot of writing is just imagining another course: If you have some anecdote and you put it in someone else's life, how would it have gone differently? I have that experience already.

Dave: What's the last book you read that you immediately passed on to someone else?

Greer: I just did it yesterday. Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell. I just thought, Everyone's got to love this book, right?

It's interesting what it isn't. It isn't a life-changing philosophical treatise that will leave you in tears, looking at your life differently. What it is, is just constant storytelling, though perhaps you have to have a slight liking for science fiction to enjoy it because part of it gets pretty science-fictiony.

Andrew Sean Greer spoke from his home in San Francisco on the morning of January 12, 2005. He visited Powell's City of Books a month later, on February 17, 2005.