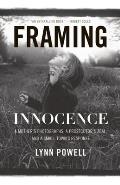

Eleven years ago, two sheriff's deputies knocked on the door of a house just down the street and took my neighbor, Cynthia Stewart, away in handcuffs. At the time, I was a poet and a mother who blissfully managed to tune out most of the small-town news. But when the local (and later national) headlines blared lurid accusations about a mother I admired, I was jolted out of my complacency. My just-published book

Framing Innocence: A Mother's Photographs, a Prosecutor's Zeal, and a Small Town's Response tells the story of what happened next in the life of Cynthia's family and in the life of our community, Oberlin, Ohio.

I had known Cynthia since her daughter Nora and my son Jesse had been in preschool. In 1999, as eight-year-olds, Nora and Jesse played on the same soccer team, shared a violin teacher, and were nervously and excitedly starting third grade together at a new school. Cynthia was one of those radiant mothers who adored her only child. She hovered, but in the most exuberant way, cheerfully nurturing her daughter's creativity and curiosity.

Cynthia was also a passionate photographer, particularly of her favorite subject: Nora. In the years since her daughter's birth, Cynthia had shot, cataloged, and stored in her cramped dining room more than 35,000 pictures. She hoped to someday publish a photojournalistic account of her family's life. But her most ardent mission was to give her daughter a photographic memory of her childhood.

Nora's childhood changed irrevocably one July day when a film-processing lab sent a roll of Cynthia's prints, including snapshots of Nora in the bathtub, to the police. When she had shot them, Cynthia hadn't thought twice about those pictures, which were a sequence of her daughter bathing and rinsing off with a handheld shower sprayer. The police and county prosecutors, however, looked at the pictures and saw a child performing a sexual act. They indicted Cynthia on two felony charges. Soon afterward, Children Services filed child endangerment charges against Cynthia, alleging that Nora was an abused child. Those leaps of the prosecutorial imagination launched Cynthia and her family into a legal ordeal that would consume one and a half years, cost $40,000, and send emotional aftershocks through their lives for a decade.

Those of us in Oberlin who stood by Cynthia and her family found our lives shaken, too. We wrote letters, made countless phone calls, held rallies, raised money for legal fees, lost sleep plotting strategy, worked the backchannels, and leveraged national media attention to coax the prosecutor into negotiations with Cynthia's lawyers. We were trying to influence the outcome of the case by taking democracy seriously. It was a passionate but improvisational effort that brought us both criticism and praise. Were we interfering with the justice system, or playing a crucial role in holding that system to its highest standards of justice?

Other questions troubled us, too, and proved to be the issues on which the prosecution and defense staked out their arguments: When does a photograph of a naked child "cross the line"? What makes a photograph dangerous — the situation in which it is shot or the uses to which it might be put? Does context matter, or is a photograph a world sealed within its thin white frame? Who decides whether a picture is cute or lewd — the parent who shot it, or the prosecutor who has learned to look through the eyes of the perverts he prosecutes?

About 30 people in our community were subpoenaed to testify for the defense in Cynthia's Children Services trial. In advance of the trial, each of us was shown the photographs Cynthia was indicted for. Seeing those photographs was a revelation. As I said in an NPR interview at the time, I was "shocked by how unshocking they were." No one in our community perceived those pictures as obscene. Although some of us knew we would not have taken those pictures ourselves, in none of our families did the camera have the documentary presence that it did in Cynthia's family. And in none of our families was the child as relaxed beneath her mother's photographic gaze as was Nora.

Yet, as a writer, I too had recorded my children's lovely and impish nakedness in the sporadic journal I kept of our family's life. I wondered: what if I were a photographer instead of a writer? Would little anecdotes I recorded, which seemed benign in words, look sinister through the wordless lens of a camera? Could the same family moment appear chaste in one medium but pornographic in another? Over time, I came to see the impulse behind Cynthia's photographic project as similar to my own — beneath the saved details of our families' lives, we shared a preoccupation with mortality, memory, the beauty of the body, the joy of seeing, the ferocity of love, and the desire to hold onto our kids' childhoods forever.

Writing Framing Innocence, I tried to be as objective as I could while acknowledging the limits of my perspective. I tried to bring to my prose the qualities I've always reached for in my poetry: economy, a vividness of detail, and a complex, nuanced truth. And like in a poem, beneath the surface of the story, I've tried to tell a larger story — in this case, about the dangers of zealotry and the harm done when self-righteousness impairs one's ability to be just.

During Cynthia's prosecution and during the writing of Framing Innocence, I learned of similar cases that have taken place — and are still taking place — across the country. Mothers in other communities have been less lucky and have had to fight battles like Cynthia's alone. I hope my book can raise useful questions for parents and prosecutors alike. And I hope this story can provide the model of one community — of Republicans and Democrats, friends and strangers — who sought to understand a family's truth, then worked together for justice.