Photo credit: James Nisbet

"A London fog is as nothing compared with the dense cloud of smoke that envelopes us and makes existence almost unendurable,” wrote an August correspondent from the Idaho Panhandle. “No rain is due in this latitude for six weeks or more, so we have to suffer a while longer with red eyes, depressed spirits, etc.”

Any present-day resident of any western state can understand all too well the summer reality of red eyes and depressed spirits. But these words were written in 1889 by prospector and plant buff John Leiberg, a Swedish immigrant who arrived in the U.S. alone at age 15. The adventurous Leiberg traveled west on a job with the Northern Pacific Railroad, and was in his mid-30s before he homesteaded on the shore of north Idaho’s Lake Pend Oreille. There he became as alarmed about the fire problem as any forester manager from our time, and equally as serious about coming to grips with it.

Leiberg identified three major causes for the rampant blazes that surrounded him: newly-arrived farmers trying to clear land; small miners like himself, who burned off rock outcrops for closer examination; and sparks from stream locomotives along tracks that were just beginning to crisscross the territory. He was the kind of man who commented on how geology shaped the region’s plant communities, and thought about the interplay between these new fires and the established landscape. He studied the way glacial impoundment and beaver-dammed wetlands contributed to soil fertility, and realized that the duff of healthy mixed-aged tree stands slowed the movement of both rainwater and snowmelt through a drainage. In Idaho’s Silver Valley, negligent mining practices had seriously compromised this system, and over the winter following the 1889 wildfires Leiberg watched avalanches overrun two active boomtowns below the devastated forest. For him it represented more a man-made than a natural disaster: “They are now reaping what they have been sowing for many years.”

He never forgot that lesson, and spent considerable effort convincing fellow prospectors to guard again careless burning. Over the next decade, as he performed assessment surveys on multiple western forest reserves, Leiberg studied tree rings so he could establish baseline fire histories that extended back several centuries. He came to understand the role of prehistoric tribal-set fires in forest maintenance, and the natural resiliency that regular burns built into a system. At the same time, he saw how the increased temperature of some recent events had led to soil sterility in certain areas, setting off a cycle of dog-hair growth and recurrent hot blazes that might take generations to eclipse.

“We try to bear good or ill fortune as bravely as we can.”

|

John Leiberg was at heart a romantic, and his enthusiasm for the forest and all its constituents did lead to some wacky ideas. He embraced a proposal to introduce Angora goats in the Bitterroot Range as a way to enhance the backcountry fur harvest. Over the course of dozens of exuberant letters, one of his pet phrases,

It is a known fact!, sometimes preceded a statement of doubtful certainty. But in all his correspondence he clearly saw the West as a region of unbounded wonder and potential that was under imminent threat on several fronts, and believed these problems must be addressed. In response, he proposed a system of reasonable regulations established by residents with long-term local knowledge that would allow the place to flourish. He then struggled mightily to implement sustainable solutions toward that end.

The smoky August of 1889 forced John Leiberg to abandon his mining digs and shelter alongside his wife, Carrie, and their young son at their Pend Oreille homestead. As a physician just beginning to forge a family practice, Carrie cast a more gimlet eye on the rough world around her. In that environment she raised a difficult child who contracted both scarlet fever and diphtheria when such contagions could spread like wildfire. Even though she managed to nurse her own son back to health each time, Dr. Leiberg tended to plenty of outside cases that ended badly. “It is a terrible thing to see a little brood of children who in a few hours may find themselves motherless,” she wrote in a private letter. “Even the best of physicians are so powerless! It is no wonder that one with either knowledge or conscience dreads the responsibility.”

The writings of other literary doctors such as Anton Chekhov and William Carlos Williams occasionally bloom into similar black thoughts, reflecting both helplessness in the face of disease and mortification for the patients who endure them. More recently, the British neurosurgeon

Henry Marsh wrote, “There is a great underworld of suffering away from which most of us turn our faces….At times, in my most despondent moments, it is not always clear to me whether we are reducing the sum total of human suffering or adding to it.”

Carrie Leiberg lived this paradox of healing and pain from the inside, in a way that would be difficult for any male doctor to imagine. When the Northern Pacific Railroad hired her as one of their first female district surgeons, her duties incorporated both the gruesome warlike wounds of train accidents and the everyday complications of childbirth within those workers’ families. When a seat opened in the Idaho legislature, Dr. Leiberg stood for office at a time when only five states allowed women to vote, promoting a suffrage platform bent on addressing the effects of poverty for women and children. When her son broke down with a psychological affliction that today might be termed multiple personality disorder, she sheltered him in her own home for as long as she lived. Although a grandniece who visited that house as a child recalled Carrie as someone who wore black and seldom smiled, the girl also absorbed vivid details of her auntie’s very human life: tending strawberries in the garden, constructing furniture in a shed out back, nurturing a parrot that kept little children in line.

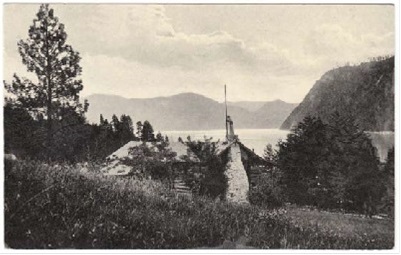

John and Carrie Leiberg’s homestead cabin on Lake Pend Oreille (courtesy of the Museum of North Idaho).

From their Idaho homestead to a farm along Oregon’s McKenzie River where they retired in 1907, John and Carrie Leiberg confronted issues of public land management and public health throughout the course of their everyday work. Both of these broad discussions continue to confound policy makers of all stripes, and while it has to be pointed out that the couple lived in very different era — John’s recommendations for sustainability were supported by scientifically minded Republicans, while Carrie’s political platform called for more stringent hygiene combined with much less gambling and alcohol — their actions still resonate across a spectrum of knotty problems. Carrie applied the same focus to a patient who had ridden on a train all day after a botched abortion as she did to her aphid-ridden homestead orchard: “We try to bear good or ill fortune as bravely as we can.” As for John, he barely waited a month after the conflagration of August 1889 before snapping back into his habitual positive frame of mind: “Three days of rain has put out the forest fires, cleared the air from smoke, and made our lakeside ranch look like itself again — the most beautiful spot on Earth I ever saw.” His certainty of that

known fact! spurred him to get down to the business of keeping it that way, not only by loving the forest but also by tackling all the chaotic uncertainties that rise, with different permutations in every new generation, between the human and natural landscape.

÷ ÷ ÷

Jack Nisbet is the author of several collections of essays that explore the human and natural history of the Northwest, as well as award-winning biographies of cartographer David Thompson and naturalist David Douglas. He lives and works in Spokane. Nisbet’s most recent book,

The Dreamer and the Doctor, follows the adventures of John and Carrie Leiberg through the greater Northwest at the end of the 19th century.