As the ship carrying my uncle from occupied Germany entered American waters, my uncle stepped outside for a glimpse of his new home. It was 1950, and as a Polish-born Jew with few surviving family members and fewer connections, he had wrangled a visa through the machinations of a distant cousin and the navigation of loopholes in the Displaced Persons Act of 1948. It was no small feat to make it to the United States in the aftermath of the war. A few powerful anti-Semitic senators had succeeded in structuring the American immigration law to limit the influx of Eastern European Jews in favor of ethnic Slavs fleeing Communism, and my uncle was lucky to win a chance to leave a Europe that to him represented death, hatred, and destruction.

Grasping his passport, holding his cap, he stood on the breezy deck as a Ferris wheel at Coney Island in Brooklyn came into view. Next to him, a Polish man, apparently gentile, pointed and said, "Look, it's the land of the Jews." There was mockery in the man's voice, and my uncle — thin and grieving the loss of all but a few members of a once-large extended family — heard in the comment the same baiting tone he had heard in schoolyard fights between the Jewish and gentile boys, felt the same threat he had felt when he returned to his hometown in Poland, "clean" of Jews after the end of the war and burbling with danger for returning survivors.

It took a second, less than a second, for my uncle to fill his chest with air and lunge for the other man's neck and shoulders, pushing him toward the edge of the deck in an attempt to throw him overboard. They struggled; my uncle was smaller than his adversary, but his fury gave him enormous strength. Then another passenger grabbed my uncle from behind, pulled him off the larger man, and dragged him away before any authorities on the boat could spot him. "What," said the rescuing passenger, in Yiddish. "You're going to destroy your new life before it begins?"

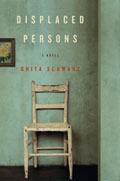

This question stuck in my uncle's mind for decades: the idea that his own rage rather than an outside force could ruin his future. With one gesture and a few words, his fellow refugee had explained that his new life would require a constant balance between striving and silence, between pushing himself forward and keeping his head down. That tension — between the refugee's need to hold onto his sense of justice and history and his desire for a safer, half-forgetful future — forms the heart of my novel, which follows four stateless Jews from their meeting in a displaced persons camp to their lives as immigrant Americans at the end of the 20th century.

The United States is at least in part a nation of immigrants, and a significant portion of American literature is also the fiction of immigrants, outsiders, and newcomers. The move from the old country to the new is portrayed sometimes as a loss, sometimes as a liberation, more often as a struggle between the two. Writers in this tradition work to capture not only the despair and pain of immigrant life, but also the joy and delight in remaking themselves as Americans, in prose that can be at once exuberant and brutal.

Exuberant because stumbling through a new language, a new city, a new way of performing ancient customs and rituals can be funny, difficult, revelatory. Brutal because, as a so-called "nation of immigrants," we are also a nation of anti-immigrants, creatively thinking up social and legal restrictions to battle the incoming hordes and their inevitable effect on those already here. More than 60 years after the passage of the Displaced Persons Act of 1948, it's hard to remember that it took enormous political will on the part of President Truman and a few outraged Congressional representatives to loosen the restrictions on the numbers of Jews entering the country. Today Jews comfortably occupy all levels of government, but in the late 1940s and early 1950s, many Americans were openly hostile to the influx of Jewish immigrants, considered both lazy (dependent on refugee assistance and welfare) and grasping (ready to do anything to survive, including take the jobs of real Americans).

Sound familiar? We're living in a powerfully anti-immigrant era, and while our current targets are different, the stereotypes are awfully familiar. I write by night, but by day I am a civil rights lawyer at an organization that promotes the rights of Latinos. Our immigrants' rights litigation practice is experiencing a growth spurt. Small towns are passing draconian laws to prevent undocumented immigrants from renting; the federal government has expanded the reach and scope of roundups of immigrant workers; and hate crimes against Latinos are increasing at a shocking rate. New Latino immigrants, as well as undocumented workers from Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean, inhabit the same contradictory tropes as so many newcomers and "displaced persons" before them: hard workers who steal American jobs and at the same time lazy, damaged criminals who drain welfare systems.

In this volatile atmosphere, is there a political role for fiction about immigrant life? Why write fiction at all if you're ticked off about current politics? A brief that I help write, if successful, will lead far more straightforwardly to a change in law enforcement conduct. Many more people are going to read a pithy letter to the editor than a short story dotted with an immigrant character's funny malapropisms. Certainly a congressional representative is unlikely to pick up a copy of a novel filled with melancholic descriptions of economic fear, children twisting out of control, confusion in school, and discomfort in the grocery store. Fiction is an odd method to protest current political conditions. When the prominent novelist Edwidge Danticat wrote of the cruelties of the U.S. immigration system — her 81-year-old uncle died after a week in a Florida detention center — she did so in a book of nonfiction.

In this volatile atmosphere, is there a political role for fiction about immigrant life? Why write fiction at all if you're ticked off about current politics? A brief that I help write, if successful, will lead far more straightforwardly to a change in law enforcement conduct. Many more people are going to read a pithy letter to the editor than a short story dotted with an immigrant character's funny malapropisms. Certainly a congressional representative is unlikely to pick up a copy of a novel filled with melancholic descriptions of economic fear, children twisting out of control, confusion in school, and discomfort in the grocery store. Fiction is an odd method to protest current political conditions. When the prominent novelist Edwidge Danticat wrote of the cruelties of the U.S. immigration system — her 81-year-old uncle died after a week in a Florida detention center — she did so in a book of nonfiction.

I don't write fiction for political purposes; I can't imagine that any contemporary fiction writer does, given the rapid multiplication of far more efficient venues to express political views. But fiction about immigrant life, even past immigrant life, gives us a kind of knowledge that nonfiction, documentaries, even feature films cannot: a window into the private thoughts of conflicted characters, an earful of the particular language of a changing community. A novel about the interior lives of new Americans will not have the effect of journalistic exposé; it won't get a bill passed in the legislature.

Instead, imaginative literature, in Ezra Pound's formulation, is "news that stays news." Stories transform the ordinary joys and stupid arguments of daily life into events with shared meaning. My uncle's story of origin as an American — the tense few seconds of a near-death fight on a boat entering the New York harbor — is of course in part a fiction, adjusted by years of his retelling and distorted by my own rendering. He tells it to his family for the same reason I tell it here: to give meaning to a history both eccentric and common, and to connect that history to the living present. One man began the process of becoming American as he sailed toward Brooklyn, sullen and afraid, counseled by a fellow passenger's warning to watch his step, and soon distracted by his own excitement about reaching shore.