Writing is running away or ? wait ? writing is

like running away. Okay, I'm too busy escaping through the door to be sure which.

The compulsion to run has always been with me, as natural as picking scabs and torturing little brothers. I still fight the impulse daily. Sit down at the desk. Do not move. DO NOT OPEN THE DOOR. Much as Lysander in A Midsummer Night's Dream plots to whisk Hermia to his Aunt's house on the outskirts of Athens, I too am on the permanent look out for a bolt-hole.

The compulsion to run has always been with me, as natural as picking scabs and torturing little brothers. I still fight the impulse daily. Sit down at the desk. Do not move. DO NOT OPEN THE DOOR. Much as Lysander in A Midsummer Night's Dream plots to whisk Hermia to his Aunt's house on the outskirts of Athens, I too am on the permanent look out for a bolt-hole.

Know of any nice houses on a Greek island I can borrow?

I could try changing my name to Adrasteia which means "not inclined to run away," but it also has the mirror-meaning of "inescapable," and there is the paradox of writing: all stories are a form of running away, but getting there ? to run with the story, to venture far into invented, fabricated territories ? can only be done whilst sitting still. True, you might walk or cycle or swim as you imagine your nameless European city where the protagonist is being followed by a chimpanzee with a hearing trumpet, but to capture it in word form you need to stop moving.

Here's a writer, perched with his laptop on his knee in a South Bank coffee shop overlooking the Thames. Here's another, hiding from the inevitable Scottish rain in the corner of a library in Edinburgh. And another, this one is a teenager; she's scribbling into her journal on the landing, ignoring the family barbeque outside in the garden.

Note the connection there? No sun. Dark corners. No movement. (Who'd be a writer? Run, now, while you can. Go quick and become a mountain climber or a gardener.) Yes, the sad reality is, to reach faraway places in the mind for a suspended period of time, perversely, the writer needs to be rooted.

This push-me-pull-me contradiction took me a long time to get my head round. Writing is an escape, and yet our themes ? our seemingly arbitrary choices of subject, mood, setting, character, plot ? are inescapable. They float up like disused shoes from the bottom of the river. Uninvited, up they come, from a mesh of seaside holidays and dreams you had at five. A fluorescent ring found in long grass at the bottom of a garden. The taste of Irish stew made with barley and dumplings. A wasp sting that happened on the same day a boy called. A rain storm on the same day a boy didn't call. The lesson learned at the age of two when your mother put you down and walked out of the door: the one you love will always betray you. We write what we are and there is no use running away from that, because when we run, where do we get to?

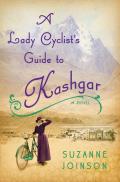

A Lady Cyclist's Guide to Kashgar is about a woman who takes her bicycle to the furthest away place in the world from London. What she carries with her, all that way of course, is her home. It is also about another woman who has been travelling and wandering, is restless and lost. What she is looking for, of course, is home.

I first ran away aged 11 or so, sneaking out through the garden gate, making my way to the edge of the housing estate until I finally reached the place where the houses stopped. I climbed over a fence, away, free into the wild woods and fields. I'd read My Side of the Mountain and planned on enacting my own version, though it was difficult to find a tree big enough to live in that part of England. I took a notebook, but that time didn't write anything.

When I was 16 and in a rage ? with parents, life, everything! ? I ran away again, but this time I was serious. I left my family home and moved into a squat in Earls Court, London. I paid £20 for a month's rent of the smallest room in a house that stood next to railway tracks. On the top floor were many nomadic Australians and the ground floor was occupied by an Anti-Nazi punk band called Creaming Jesus. I curled up in the room and read. I remember in particular reading Toni Morrison's Jazz, and the words on the page and noises I heard from the strangers in the other rooms and sound of the trains on the line outside blended into city-song that seemed to be saying: What are you doing here? You're not ready for the city. My parents came and got me. Poor parents, I was trouble as a teenager.

I ran away to France at 18 to be an au pair but it didn't last that long. I wasn't very good. I was okay at the papier-mâché projects with a two-year-old but less impressive at the housework and domestic-help elements of the job description. I was allowed to use my boss's word processor once the kid was in bed, so each night I wrote awful poetry heavily influenced by Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath, whom I read whilst changing nappies. I could have won a medal as the world's most pretentious au pair. I also wrote lots of letters; I miss letters.

After that, through my 20s, I'm afraid to say that I bolted on a series of boyfriends. I got claustrophobic in my head easily and left a string of broken hearts on the pavement behind me. Well, maybe not, maybe just some frustrated and fed up chaps, depends which way you look at it. But I kept writing short stories, which mostly came out crooked and awkward and wrong, though I did get one published in a magazine. It was called "Cowboy," about a dad who had run away.

Then I found a job which involved a lot of international travel and finally salve to my itch. The panic, the desire to flee, the skittish flitteriness of my earlier days subsided as I spent more time in hotel rooms.

Ah, hotel rooms.

I started to write longer pieces now, stories infused with the transience of hotel-room life: lonely flashing lights outside, blackout blinds too black, pillows too hard, and club sandwiches that were impossible to eat. I wrote in seven-star rooms in Arab Gulf countries where I was not allowed to use the swimming pool because I was a woman, and in two-star rooms in Novosibirsk, Siberia, where there was no TV, just a Soviet-style radio and a picture of Lenin. Scratches on notebooks and lost memoires, cities all blurred and stories emerging.

The books that meant a lot to me as a teenage reader, all, I realise now, involve running: Jane Eyre fleeing Rochester, or Tess of the D'Urbervilles on the run having killed a man, and most important and formative of all, Alice, fleeing the Victorian world of her sisters and falling, falling. Later, I read Virginia Woolf's first novel, The Voyage Out. The title says it all really. Many people disregard this book, but her beginning, her launch ? the metaphor of the journey, the need she had to send herself off before she could look backwards at her home and self ? all made sense to me.

I can't pinpoint the moment I decided to write about English missionaries who travel so far from England, but I can tell you how I finally sat still enough to write it: reader, I had a baby (well, I fell in love and got married, too, but that's a different story). Having a baby meant no work for a while and no travel, and when the red-faced, arm-waving howler was six months old my husband and I came up with a scheme: he would have the baby from 9:30 a.m. to 1:00 p.m., and I would go to my writing cafe. We would all have lunch together and then he would go to his studio, where he would usually stay until the small hours.

Oh, sweetness. It worked!

In those three-and-a-half-hour slots I wrote my novel, sitting in the basement of Starbucks on the Pimlico Road, London (hi, staff there, if you are reading this ? remember me?). It was perfect: no WiFi, staff who didn't mind that I made a green tea last over an hour. The basement was a bit dank and had an odour problem and so it was always empty, apart from me, and a miracle occurred: I stopped running and stayed still and wrote about some other women running instead.

Now that I'm a Grown Up I have my own room with a desk and a view over a railway track. I watch trains rush past, and it's still a battle to get into that room: a fight with the washing up, washing clothes, procrastination, picking up kids, dreaming dreams, reading books, exciting and distracting projects. The trigger, the impulse, the rush to jump on a plane is there ? and sometimes I do, still, jump on a plane ? but I've discovered the trick. I write it out. I remain still, at my desk. DO NOT OPEN THE DOOR. I turn the burning desire to see the backstreets of Cairo into a story, and that way, I'm as free as it is possible to be.