When I first met Dolma Palkyi, a 17-year-old Tibetan refugee, our conversation was awkward and faltering. She barely looked at me, partially bored with the questions Western journalists like myself kept endlessly asking her, and, at the same time, nursing a very deep and private internal trauma which she did her best to keep to herself.

Just a month earlier she had watched the murder of her best friend, Kelsang Namtso, a Buddhist nun shot to death by Chinese border guards as they were trying to flee Tibet to India over the Nangpa La pass. The two girls were escaping Tibet with around 70 other refugees seeking freedom in India, where they could practice their religion without persecution by the Chinese authorities, and a chance to meet the exiled Dalai Lama. Around 100 Western climbers on Choy Oyu, a mountain 19 miles east of Everest, witnessed the killing. Many of them were vainglorious mountaineers who saw the conquering of the peak as glorious validation of their often humdrum lives in the West. When they witnessed the killing of Kelsang, many didn't say anything for fear of losing their lucrative climbing permits and others due to a suspicion that the Chinese would ban them from coming back to climb more mountains.

I had been assigned by a magazine editor in London to travel to the Tibetan border regions and to report on the issue of Tibet. I knew nothing about the topic but set out to find "victims" ? as journalists do. This was easy enough once I got closer to the approaches of the Nangpa La and met Tibetan refugees crossing from Tibet, 2,500 a year back then. They brave temperatures of -40, the constant risk of avalanches, crevasses, and starvation, and the constant risk of being murdered by Chinese soldiers or thrown into jail. They looked like they were escaping a war zone.

Shortly afterward, I met the Dalai Lama. He was angry as we spoke about the murder of Kelsang Namtso. "This shooting is not a new thing!" he railed with disgust. "Just, this time it was seen by Westerners. They have been killing and shooting like this for years!"

As he began to speak, it became clear that Kelsang's death had unleashed a powerful, personal sense of injustice within him. The circumstances of her murder had highlighted Tibet's plight to the world. Yet he was furious that it had taken a young woman's murder to illuminate the injustice served by the Chinese to the outside world. The West's apathy with regard to Tibet was, as he understood it, the result of racism and blatant self-interest. "In the '60s, '70s, and '80s, we went through incredible suffering," he explained. "But they [the West] all looked at Russia and not China." His chest was heaving as he spoke. "Perhaps it is because we are Asian, they don't care!" he snorted, giving a dismissive flick of his wrist. "So you see, there is even discrimination in human rights!"

Before I took my leave, the Dalai Lama offered me words of advice. He told me what he told everyone else he had met who had been connected to the Nangpa La incident. "Just be honest and tell the truth." It seemed strange advice at the time. Why wouldn't I?

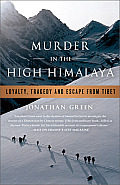

My quest to discover the truth about Kelsang's death began with two magazine articles and has ended with the publication of Murder in the High Himalaya. What I found along the way challenged and constantly surprised me. It was a journey a few times I never thought I would complete. I almost quit when I ran out of money or, time after time, people refused to help or sit for interviews. I met walls of silence almost everywhere I searched: climbers, NGO's, respected experts on Tibet. No one wanted to risk China's wrath and be banned from China. And Tibetans were terrified, and with good reason, that if they spoke publicly about Chinese human rights abuses in their homeland, the Chinese authorities would target their families at home.

Despite this, Dolma Palkyi, through our conversations, stood up to tell the truth of her friend's murder, no matter the cost to her. We got to know each other over several years: she, the female teenage refugee from rural Tibet with no formal education who had never met a Westerner before, and me, the 30-something, white male journalist with the high-flying career and a sometime reputation for bravado. At first, it was a difficult relationship. I needed details of the horror she and her friend had endured. In Tibetan culture, so deeply intertwined with Buddhism, one is discouraged from talking about personal suffering. I needed all those details.

Some of my career as an investigative journalist writing for men's magazines has been a vainglorious affair. I began my freelance writing life with a piece in Esquire about being beaten up by skinheads in London; all my front teeth were kicked out and I was rendered unconscious. Since, I've skydived from 30,000 feet with members of US Special Forces in a record-breaking HALO, ridden a bull, faced temperatures of -30 while stranded in a blizzard in Alaska, survived a 198 mph blowout in a Dodge Viper writing a piece on a road in Nevada for Esquire, scuba dived under ice, spearfished at 60 feet with soldiers at Guantanamo Bay, ridden the entire length of the Mississippi on a jet ski, covered human rights abuses in Colombia, Sudan, Brazil, all over Africa, any one of a number of hotspots.

In recent times I began to feel I had been on an egotistical mission for many years, much like the climbers in my book. But, through Dolma, I began to understand what real courage and self-sacrifice really were.

My perception of the media that I worked in changed. I realized that as journalists we like to create heroes in our own image; we have a white, western male outlook. But what I learned from Dolma was that the real heroes of the world are who you least expect, that those you think are victims are in many ways heroes, and those you think are heroes, are actually manufactured to appear as such. Something for which some journalists are willing conspirators.

This year will be the fifth anniversary of the murder of Kelsang Natmso. Her murder continues to play out on a viral loop on the Internet, making us all witnesses to Chinese atrocities in Tibet and to the murder of Dolma's best friend.

Dolma has matured into a remarkable young woman in the time I have known her. Our friendship has deepened, and I've come to understand that Dolma is no victim. She's a heroine. And today she speaks with self-assuredness, passion, and clarity. She found her voice. And I found mine.

And, I learned through Dolma that the human spirit, no matter what it endures, is strong and unquenchable. And that it liberates and soars in the most adverse and extreme circumstances, often quite unexpectedly.