When I was eight I stole a dragon. That was 20 years ago. It was a good day for firsts: it was the first dragon I'd ever come across and the first time I ever stole. It was also the first step I ever took towards being a writer.

I was at school.

My teacher (whose name I can't remember, but who looked a little bit like a furtive Daniel Day-Lewis with shadowy eyes) didn't turn up. Usually this meant the class being split up into twos and threes and each group being sent like refugees to another, already packed classroom, where we'd sit apart from the native children by the sink, fearful and foreign, supposedly doing sums or reading but instead, as was my habit at the time, working on complicated doodles in the back pages of my copybook (usually of ninjas, often as they braved improbably dangerous assault courses).

For some reason though, myself and two others (girls, I think, who like the absent teacher I don't really remember) were told we were to stay in our own classroom, unattended, while the rest of the children were marched out to their new, temporary homes.

What?

On our own?

Yes, on your own. You can be trusted can't you?

Of course. Of course we could be trusted.

This was amazing. It was great. It was — as Dubliners sometimes say — deadly. Pure deadly. I wasn't a mouthy or troublesome kid and I had no intention of running wild. Maybe the powers that be knew that and that's why I was put in this strange position — left in a nearly empty classroom, unsupervised, from nine a.m. till three p.m., with nothing in particular to do.

The teacher from across the hall left. She said she'd check in, from time to time. For a while I just sat there, flicking through my schoolbooks, doodling, thinking about ninjas and dinosaurs. I wondered how many ninjas it'd take to bring down a Tyrannosaurus rex. Loads, probably. An army. And they'd probably need a few samurai as back up, as well. Then I got restless and wandered around the classroom. I idled by the coat rack, hung and re-hung my coat on different pegs, turned on and off the taps at the sink (it seems weird now, thinking back, that there were sinks in the classrooms), peered through the cloudy Perspex windows at the empty yard. Then I turned my attention to the shelves. There was lots of stuff there — jars full of brushes with rainbow-stiffened bristles, stacks of colored paper, boxes of chalk and crayons and rolls of tape. And books, too. But boring books, schoolbooks. Books like Anne and Barry and the vile Busy at Maths. God, I hated maths. I was terrible at it. I hated that, if you weren't right, you were wrong. As I cast my eye over them I was disappointed. Being left in the classroom without a teacher wasn't as great as I thought it'd be.

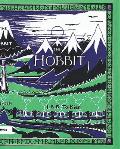

And then I saw it.

The dragon.

I stood on the sink to get a better look. It was an elongated thing with a head like a reddish-gold alligator, and it was curled up on a pile of riches. It looked friendly and sly at the same time.

I had to have it.

I looked about. The two nameless girls (they might have been nameless to me even then — girls were a world apart) were talking to each other, completely uninterested with what I was up to. I looked back at the dragon. I didn't think about it, or not much, and took it. Took it all — not just the dragon, but the riches too, and everything else, the whole world that the dragon and the riches were part of (an immense world, as it turned out, a world and a history of a world). In one swoop, at age eight, I owned a dragon and I was a thief and with the dragon's gold I made a down payment on my future career as a writer.

I still have that book today — a nice, old paperback edition of The Hobbit from the 60s. I was in a terror after I took it. It was as though the dragon (Smaug, I'd later know him as, when we got on speaking terms) was trying to burn his way through my schoolbag with his breath, to escape and tell everyone I was a thief (which was a bit rich, since, I would later discover, Smaug had stolen all the gold and jewels he used as a bed from the dwarves of the Misty Mountain).

I still have that book today — a nice, old paperback edition of The Hobbit from the 60s. I was in a terror after I took it. It was as though the dragon (Smaug, I'd later know him as, when we got on speaking terms) was trying to burn his way through my schoolbag with his breath, to escape and tell everyone I was a thief (which was a bit rich, since, I would later discover, Smaug had stolen all the gold and jewels he used as a bed from the dwarves of the Misty Mountain).

When I got home I made my way upstairs and began to read. Even though I was alone in the room, I hid behind a schoolbook as I read, convinced my mother or father or the teacher whose name I've forgotten but looked like a furtive Daniel Day-Lewis with shadowy eyes, would burst in and catch me in the act of reading the stolen words.

But they never did, of course.

I read the book over the course of a few days, worried and in utmost secrecy, and began to fall in love (in an unknowing kind of way) with not just Smaug and hobbits and dwarves and elves and the sad and maniacal Gollum, but with the very language that created them, the word-spells Tolkien wove (Tolkien, that real life Gandalf), word-spells that summoned them up from the page and into my child's head (the best place of all for words).

It took Bilbo Baggins a few weeks (or was it months?) to reach Smaug and his stolen lair, but it only took me a few days. Neither of us forgot that hoary, sly old dragon, though. I met Bilbo again, reading The Lord of the Rings, when I was 10 and Bilbo was 111, and both of us still often thought about our confrontation with the great fire drake Smaug. I'm 28 now and Bilbo has long since passed from the world and into the Grey Havens, and, once again, Smaug is on my mind.

It took Bilbo Baggins a few weeks (or was it months?) to reach Smaug and his stolen lair, but it only took me a few days. Neither of us forgot that hoary, sly old dragon, though. I met Bilbo again, reading The Lord of the Rings, when I was 10 and Bilbo was 111, and both of us still often thought about our confrontation with the great fire drake Smaug. I'm 28 now and Bilbo has long since passed from the world and into the Grey Havens, and, once again, Smaug is on my mind.

Writing — good writing — is a spell, a weaving of words that creates bonds and worlds, and shapes lives. Reading a good novel is a miraculous act, a telepathy between reader and read, a profound sharing. It's an adventure, a trip to and back from the dragon's den, a trip from which we return not quite the same.

My name is Trevor Byrne. I'm a writer and a thief and I believe in dragons.