I was crying or almost crying for most of

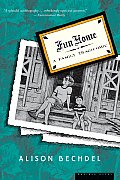

Fun Home: The Musical — I already loved

Alison Bechdel's graphic novel, and I've always been a sucker for the way musicals make melodrama catchy. The song that got me most was "Ring of Keys," a song about a primal moment of identification: Sydney Lucas, playing a young Alison, is at a luncheonette with her father, and a butch delivery person comes in. She's never seen a woman that looks like that before — with her "short hair...dungarees, lace-up boots" and her significantly hefty ring of keys. I lose it within the first few bars. It's this beautiful moment of admiration and discovery, a sense of possibility and opening up.

Watching Lucas perform this song, letting my tears brim and spill over, I almost believe that it's my story. I want it to have been my story. I want to claim that prototypical queer narrative: that I was a tomboy who hated wearing dresses. That I fell in love with my best girl friend in second grade. That I saw a butch lesbian in a diner and a world opened up.

Instead, the first time I saw lesbians I was disgusted. It was at an Indigo Girls show my freshman year of high school. My proto-alternative-hippie-lite friends and I were pretty into their songs — but I think we were actually at the show because Matthew Sweet was opening. I don't think I knew the Indigo Girls were lesbians. Or, it wouldn't have occurred to me to think they might have been. We got to our seats and I saw two women a few rows ahead of us making out. I turned to my friend Eva and said, "Do you see those women kissing?" Maybe disgust is the wrong word. I was surprised. I had nowhere to put what I was seeing, no frame for making sense of it, and so I pushed it away. (Eva, to her credit, said "What's wrong with that?")

Surely, some deep-buried internalized homophobia was also part of it. There must have been a flicker of recognition that I clapped out as quickly as I could. There must have been, it makes sense that there would have been. But I can honestly say that when I looked at those women, I fully felt that they had nothing to do with me.

Can I say this had something to do with what kind of lesbians they were? That they had mullets and wore flannels and I was an upper-middle-class kid from the suburbs? Can I say that I had never kissed anyone, that I had articulated crushes on boys but I didn't know what it was like to experience that crush with a body-feeling? Can I say that most of the time I felt like I didn't have a body? Or — I didn't feel myself having a body?

÷ ÷ ÷

Bechdel's moment in the luncheonette was as much about gender as it was about sexuality. It was a mirror moment — she saw the delivery person and she saw herself. I think she had to have a sense of her own embodiedness in order to have that moment of identification — even if she felt she was wrongly embodied. The friction of that wrongness produced awareness. I always felt kind of unsuccessful at being a girl, but I mostly wanted to keep trying, or didn't know what to do but to keep trying.

÷ ÷ ÷

A year or so after the Indigo Girls, I went away to a summer program at Bennington College. I took music and playwriting classes. I'd gone with my best friend from home, a guy I'd had or thought I had a crush on, and though I was over it I still always felt as if I had wanted too much from him. At Bennington, there were way more girls than boys. The girls were incredibly cool. Differently cool from the cool girls at home. They were painters and poets and they made films. They smoked. They gave themselves different names for the summer. Some of them were bi.

A year or so after the Indigo Girls, I went away to a summer program at Bennington College. I took music and playwriting classes. I'd gone with my best friend from home, a guy I'd had or thought I had a crush on, and though I was over it I still always felt as if I had wanted too much from him. At Bennington, there were way more girls than boys. The girls were incredibly cool. Differently cool from the cool girls at home. They were painters and poets and they made films. They smoked. They gave themselves different names for the summer. Some of them were bi.

I knew this because they talked about it all the time, while they smoked, while they lounged, leaning on each other. I sat near them, listening, wanting to be leaning with them. I wanted them to lean on me. I wished I smoked. I wished I wore more black. I wished my hair was already the magenta Manic Panic I would dye it when I got home.

I was in love with them, and now I had a name for it.

And once I could put a name on how I felt about these girls, I could find girls from the past and feelings from the past and draw lines connecting them. The camp counselor who was "so pretty" I didn't want to stop looking at her picture. The way my crushes on boys had always felt somewhat like scripts I was following. The way I wanted an intimacy with my girl friends that I could never figure out how to forge.

One of the Bennington girls in particular I loved and I think she knew it. I think she realized that when she lay down and cuddled with me on my bed it made me feel crazy, even though I told myself If she knew I felt that way she would never lie with me like that. (I still didn't feel like I had a body.)

What I'm trying to say is, before that summer, I didn't know anyone gay. No one talked about it. There was nobody gay in culture, or nobody gay I wanted to be. For a long time, until I was well out of high school, I couldn't map a sense of gender or sexual desire onto myself. When I was 16, I needed a narrative of queer identity that hit other parts of me — art, brain.

÷ ÷ ÷

My summer at Bennington wasn't just about those girls. It was about my roommate, who listened to indie bands and made zines, and all the films and books everyone watched and read and talked about. It was about punk rock and getting political. By week two of the program I had ditched my best friend, telling him that I wanted more from life than sitting around watching TV in our friends' basements. He said, "What are you going to be, Gandhi?" When I got home I immersed myself in college radio and going to shows and mail-ordering zines, alongside this new revelation that I was into girls, and it wasn't long before the two strains converged. Riot grrrl, queer punk zines and bands, Team Dresch's Personal Best, the 22-minute LP I copied onto a cassette so I could listen to it over and over in my car on the way to school. I hated the Indigo Girls.