It was in the middle of a gray and brittle February when I approached the wrought-iron gates of the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. I was already elbow-deep and several months into researching my book,

A Grand Complication. I had read letters, diaries, and books, as well as countless newspaper clippings, yellowed documents, telegrams, and even hotel menus. I pored through photographs, conducted interviews, examined bound auction catalogues, and deciphered archives written in a florid pen abandoned long ago. I was hot on the trail of the two men at the center of this intertwined story: James Ward Packard and Henry Graves Jr., which is what brought me to the graveyard made eerily famous as the setting of Washington Irving's

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.

Two of the greatest watch collectors of the 20th century, Packard and Graves had embarked on a quest to possess the most complicated watch in history, resulting in the Graves Supercomplication. And I was hot on the trail of their timepieces too. I had stood before vitrines examining magnificent mechanical watches in museums in New York, Geneva, Jerusalem, and London. On several occasions, I had the great good fortune to hold in my own hands a few timepieces that now belong to private collections.

Beyond the watches, I wanted to know about the men in whose pockets they had once ticked. To do that, I had to exhume their histories from a fortress of time. Packard had died in 1928 and Graves in 1953. Theirs was a tale told through a prism of precious objects, and so I began by tracking down the remnants of what they had left behind. The pair had lived during a time in America when tremendous fortunes were made. A period animated by ostentation and flamboyance. Vivid men during their own lifetimes, they had in the ensuing decades largely faded into history's crowded margins.

Of the two, Packard had left the larger footprint. An engineer and inventor, he had founded the Packard Motor Car Company, America's first luxury car, in Warren, Ohio. His horological rival, Graves, a financier and art collector, proved more difficult to excavate. In both life and in death, he had maintained a fiercely private existence. Remarkably, few had sought to examine the life of this Gilded Age scion, a man who had moved through New York society with gracious aplomb. As I was writing about a person long since dead, it seemed to make sense for me to meet him where I could.

Graves was buried at Sleepy Hollow and so I decided to pay him a visit.

I made my way from the pathway to the white marble mausoleum, the snow crunching beneath my heavy black boots. The mausoleum stood on a prominent slope, with the Graves name carved in the pediment above an arched doorway decorated in a motif of carved grape vines. I pressed my face right up to the glass doors wrapped in a filigreed screen of oxidized copper. I took a deep breath. I'm not exactly sure what I expected to find, but as my eyes adjusted to the strange optical effect, my heart leapt. Inside, a stained glass window depicting Jesus tending sheep lit up the dark, somber space. Straight ahead of me appeared a giant slab of polished granite that held the bodies of Mr. Graves and his wife. There he was. I felt both exhilarated and macabre.

Quickly, my eyes shifted back up to the mantel where I spied two vases filled with flowers. They flanked a large, ornate crucifix and, to my utter surprise, a long-eared, stuffed white bunny. The sight immediately cut through the haunting serenity of the mausoleum's interior. It would be some time before I discovered the meaning of the bunny, but what became strikingly clear to me as I sought to understand these men was that, more than anything, it would be the objects that each had left behind that would open up their worlds and decipher their lives.

They belonged to an era defined by transformative objects: incandescent light bulbs, railroads, Newport cottages, tenement buildings, telephones, automobiles, radios, and the moving picture. Entering their lives was like falling into a newly discovered treasure chest. Their possessions came to speak for the gentlemen who could no longer speak for themselves.

It began with the timepieces. Glorious, transcendent instruments, they were microscopic universes that revealed the men's inner lives. Packard, a brilliant mechanical engineer, favored complex watches of the highest technological achievement, housed in elegant cases of repoussé, extravagant engravings, and his stylized monogram in enamel. Intensely competitive, Graves viewed collecting in the same vein as sports — he was out to win. This did much to explain his obsessive attachment to Geneva Observatory prize-winning chronometers. Encased in gold or platinum, he embellished his timepieces with little more than the plumy Graves family crest, featuring the Latin motto: Esse Quam Videri (To Be Rather Than To Seem).

Aside from these remarkable treasures, there were also numerous large possessions: the mansions, country estates, and slick motorboats. But it was often the small, overlooked objects that I came across that provided other intriguing glimpses into their private worlds. A small crystal cut perfume bottle topped with a gold stopper and encrusted with diamonds, emeralds, and rubies expressed a husband's privileged affection toward his wife, while a gold locket that held a photograph and a lock of hair represented a mother's anguish. A baby elephant foot lined with copper and used as an umbrella stand told other stories. A pair of wooden bar bells with a faded stenciled monogram, dozens of glass photographic slides, a barometer, a leather steamer trunk empty save for ostrich feathers, a silver candy dish, a dinner bell, and monogrammed picnic knives, spoke of lives filled with joy, sorrow, power, curiosity, conquest, luxury, tenderness, and triumph. Sadly, I came to discover that the plush bunny marked a life cut much too short.

As I pondered these items, some modest, some splendid, it brought to mind visits to the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, DC, with its display of Lincoln's hat, Dorothy's ruby slippers, and Fonzie's jacket, and the three-dimensional encyclopedia of civilization that is the British Museum, keeper of the Rosetta Stone and the Elgin Marbles. That is the thing with relics of the past. With the passage of time, they become more than just objects but defining symbols, mystical talismans connecting us across time to the people who owned them and the periods in which they lived.

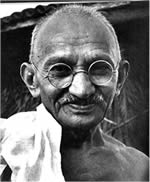

I think of how Mahatma Gandhi eschewed material comforts and lived a life of austerity — and yet possessed some of the most iconic objects in recent imagination. It is hard to conjure up an image of the man who wrested India from the claws of the British Empire through nonviolence without his spinning wheel, round eyeglasses, and rice bowl. Indeed, his few belongings had become so imbued with symbolism that, in 2009, his glasses, pocket watch, sandals, plate, and bowl fetched $1.8 million at auction.

I think of how Mahatma Gandhi eschewed material comforts and lived a life of austerity — and yet possessed some of the most iconic objects in recent imagination. It is hard to conjure up an image of the man who wrested India from the claws of the British Empire through nonviolence without his spinning wheel, round eyeglasses, and rice bowl. Indeed, his few belongings had become so imbued with symbolism that, in 2009, his glasses, pocket watch, sandals, plate, and bowl fetched $1.8 million at auction.

There is a certain unassailable power in objects. But is it objects that define us, or do we define the things that we come to possess during our lifetimes?

In the end it was a single object, the Supercomplication, that plucked Henry Graves Jr. from certain obscurity. This great collector had surrounded himself with the most lavish possessions that money could buy and shrouded himself in refined discretion. Yet, it was precisely his desire to own the most complicated timepiece ever crafted that became his legacy. The watch captivated horology. It defined an era and a man. And for that he will be remembered.