Gina Frangello reads from her new book, Slut Lullabies, at Powell's on Hawthorne this Thursday, July 29, with Zoe Zolbrod (Currency). In our newest installment of Small Press Conversations, Frangello, a writer, teacher, publisher, and editor, speaks with Davis Schneiderman, author of the novel Drain. This conversation happened before Gina and Davis's event in Iowa at "Live from Prairie Lights" on July 22, 2010.

÷ ÷ ÷

Gina Frangello: Given that so-called experimental writing has characterized certain major literary movements at least since the modernists, how would you define experimentalism a century later? And why, if writers have been experimenting with form, some finding great acclaim for that in the modern and postmodern eras, going on to be regarded as canonical writers, is formally innovative or avant-garde writing still regarded as a "fringe" part of literary culture? What characterizes the type of experimental writing that is primarily the arena of indie presses?

Davis Schneiderman: Yes, oh yes, it seems that in 1922, a year that some have called a high point for modernism, with a capital M, we could still find a big difference between a writer type such as Thomas Mann with his mountain magic and the surrealists with their automatic writings magnetic fields broken trestles of nightmare trains chugging to Auschwitz not so many years off-then when a dada-collage a screaming poem word a poem life like that of Jacques Rigaut who announced his own suicide and then in 1929 made good on his words oh yes oh yes oh yes.

Oh, no.

Today, it's all modern or postmodern experimentalism.

Actually, Gina, I don't think experimentalism is on the fringe as much as some like to think. Certainly not in visual culture where the cut-ups of Burroughs and Gysin suggested the mash-ups the jump cuts the less-than-a-flash quick shots in every commercial to infinity and beyond. Our pop culture drank its own Kool-Aid decades ago. In literature, we've elided so many transitions, so many slow moments of supposed human realism, that even the most realist novel of today might seem like a three-minute video compared to some über-tome of the mid-to-late 1800s.

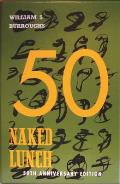

To address the last point, for me the indie press — if there is such a thing, really — makes work that can not or, at least for some period, should not be recuperated easily back into the mass of literary and popular culture. Naked Lunch still fascinates me 50 years later because it doesn't make any more "sense" (once you toss away the insufficient William Lee-quitting-junk explanation) than it did half a century ago. This is a highly unstable novel because it's not a novel, really, by any definition of the novel put forth in the last two centuries of literary criticism. As my colleague in all-things-William-S.-Burroughs, Oliver Harris, has shown, Naked Lunch emerged from letters, epistles. Accordingly, its genetic history disputes most of the author-centered discourse of our current age.

To address the last point, for me the indie press — if there is such a thing, really — makes work that can not or, at least for some period, should not be recuperated easily back into the mass of literary and popular culture. Naked Lunch still fascinates me 50 years later because it doesn't make any more "sense" (once you toss away the insufficient William Lee-quitting-junk explanation) than it did half a century ago. This is a highly unstable novel because it's not a novel, really, by any definition of the novel put forth in the last two centuries of literary criticism. As my colleague in all-things-William-S.-Burroughs, Oliver Harris, has shown, Naked Lunch emerged from letters, epistles. Accordingly, its genetic history disputes most of the author-centered discourse of our current age.

The most interesting literature to me, and it need not be "experimental" or "postmodern," takes the author and makes her disappear or at least dissolve a bit into the Proustian tea. Now, I realize that this comes across as bullshit, since you've seen me read and I have a bit of a reputation for the booming-voice-gimmick reading. Recently, the night after we read at The Book Cellar (Chicago), I borrowed Cris Mazza's starter pistol and shot Artifice editor James Tadd Adcox, twice. The first time fit in with the text, a bit from my new novel Drain where Lake Michigan empties of water, but the second time was really gratuitous, pure superfluity. That's the excess I look for in literature, independent literature, and I hope to find this even when the literary style is spartan, spare, nothing.

I think you have a different view of indie publishing. I see Other Voices Books (OV), whose works I love and keep by my bedside for easy access (I also have two copies of Slut Lullabies, btw), as publishing work that might have once had a home with the larger houses, yet has been squeezed out because of the dismal state of corporate publishing. Devil's advocate: aren't those types of texts, not necessarily from OV, but those perhaps not recognized by a bigger house yet still "good" according to its tastes, just reaffirming the values of mainstream publishing, and, in a cool Derridean twist, further eroding the audience for anything different?

Frangello: That's a question within a question within a question, which I love. I'm going to go from the back and move to the front — so, first, when you say "its tastes" with regard to the bigger, corporate houses, I want to say that I think the "It" has radically changed, even just in the past couple of decades, so that there are different Its we could be talking about. To me, the It right now in big New York publishing consists of marketing departments (comprised of people with some kind of business degree) and corporate shareholders. So, in the bluntest possible terms — which always risks broad generalizations — we are talking about a group of people who do not define themselves as "literature lovers," necessarily, of any kind. Some of them may not even read for pleasure. We are talking about big publishing being defined, almost entirely now, by people in the business sphere, not the editorial/creative sphere. Editors at the corporate publishers hold almost no power anymore. Unless you're Jonathan Galassi or something, you have no ability to just love a book and thereby publish it. You have no job security, and you live and die by what the marketers and shareholders have to say about your bottom line fiscal performance: whether the projects you acquire make money. Period.

Given that, I want to say that I don't believe editors of indie houses and editors at big houses are necessarily on opposite sides of a taste or culture fence — I just think that the choices we're making about how we live and work are radically different. I believe that many editors at the big houses are every bit as well-read, as interesting, as sophisticated in their tastes, as intelligent, as complex, as editors at indie presses — but they have chosen to try to make a living (not a great living, I should specify, but some living) from their work as editors, in a big arena where they have almost no control. Indie editors have other day jobs, such as being academics or freelance copyediting or something, and so we still publish what we love and retain far more control, but usually make very little — or sometimes no — money on our publishing endeavors.

So yes, you're right, I do often discuss Other Voices Books as a boutique indie that publishes the type of literary fiction that the old model of New York publishing was more receptive to. Keeping in mind that the small press tradition has existed for a long time as an alternative to bigger publishing — look at the Hogarth Press, for example — I think the divide between what was published in these two arenas has recently widened significantly. Until fairly recently, many of my favorite books — books that changed my life — were still coming out of mainstream publishing. Not all, but many. Doctorow's The Book of Daniel or Kundera's The Unbearable Lightness of Being, early Mary Gaitskill. But I believe that these books would have a very, very hard time being published in the corporate arena today if written by new writers, and that they would probably end up "indie" books. Doctorow and Kundera are, in fact, experimental writers, at least in some of their books (Book of Daniel would probably be called unintelligible and schizophrenic by a current corporate publishing marketing department). They break all the rules of what the big houses want these days: black-and-white morality, plucky and "sympathetic" protagonists, tight and linear narrative arcs. So I am not bothered by saying that Other Voices Books very much hopes to continue to champion, to whatever degree we can, writers who are carrying that kind of torch — writers who at one time would have been hailed as some of the best and most daring of their generation — but whom marketing departments and shareholders have no interest in because, no matter how many good reviews they get, they are never gonna sell like The Da Vinci Code or The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. I believe editors, at big and small publishers, still very much recognize the talent in these types of writers, but the big house editors are powerless to champion them unless they've already found success in a previous generation, or unless they come with a particular pedigree or platform that makes them easy to "sell" despite their risky work.

What I mean is, I don't see Other Voices Books or similar torch-carrying indies as being not receptive to work that pushes — or breaks — boundaries, or innovates. I don't see literature, or literary fiction, as being averse to those things. If anything, part of what defines literary fiction, essentially, is the fact that it doesn't adhere to formulas, and therefore new things are always possible and should always be happening, formally and in terms of content and philosophy. But I very much want to embrace an inclusive model of publishing that I think has been lost, where traditional and innovative modes of serious fiction — work that accomplishes far more than just "entertaining" in the moment — don't have to exist on opposite sides of a cultural divide, or as enemies of one another, but can both be important aspects of art and culture. I am OK with reaffirming some aspects of what used to be mainstream publishing culture, as long as I keep in mind that what we call mainstream publishing at one time included rule-breakers and innovators, but the next generation of trailblazers were the first to be pushed out of that model, and now they're the ones indie presses are lucky enough to be able to take into our folds.

OK, I'm done now. But I'd actually love to go back to your discussion of author readings. You do have a distinctive reading style and are also widely known in our community as a really funny, personable guy, constantly game to collaborate and try new tricks (like, uh, shooting a pistol at a reading). Can you talk about the writer's role as performer in today's literary climate? I mean, for many years writers were regarded as introverted, solitary beasts, and it was possible to attain great fame despite — or almost by — never leaving your house or giving an interview. These days, publishers pretty much require writers to go out and "work it" on blogs, on tour, on Facebook and Twitter. Talk about the up and down side of this.

Schneiderman: OK, I'm glad you asked this. I have, probably, the world's shortest attention span at readings. I find it very hard, nay, almost impossible, to pay attention to any sort of sustained narrative, or even, heck, a single short lyric poem when someone else is reading. I think if Abraham Lincoln or Cicero were giving a speech, my mind would be a million miles away. Part of this is a function of my own incessant loquaciousness. When other people are talking, I usually want to talk — and "listening" for me (and I fully realize this may be a character flaw) is simply the time to gather my next thought or quip or joke or just plain-old-speech-act.

I will always, also, sacrifice content for laughs, and I often go into professional meetings reminding myself to actually listen and to hold back from breaking in with something I think may be amusing. I even enjoy when a joke fails, because I love, absolutely love, the uncomfortable silence that follows — the sound of "thick air" in a room. All of these things break through the monotony of the everyday and make a small rent in the fabric of the quotidian.

So, I want readings to be this way as well. I want to listen to someone who captivates me, someone I can't help but listen to, or someone who at least makes my own inner thoughts richer for the interplay between the zillion miles I am covering in the mental landscape and the words I am hearing being spoken. When Christian Bök joined us for the &NOW / Northwestern / Artifice reading at the Association of Writers and Writing Programs (AWP) 2010 conference in Denver (which you were kind enough to participate in as well), he performed a five-minute section of Kurt Schwitters's Ursonate — all voiced non-words — and damn if that wasn't the best thing I've heard in forever.

When I first started curating readings after my arrival at Lake Forest College in 2001, I would invite writers whose work I enjoyed. On occasion, I would find myself so bored to tears during the reading — in a state akin to windshield wiper hypnosis — that I could feel the poor students, already forced to be there for class, disappearing further into a room where literature shall never again enter. Call this a hyper-awareness of the importance of performativity at the expense of "content," but I do believe that writers — when reading — need to do more than read. After all, if someone is going to deliver like Ben Stein in Ferris Bueller's Day Off, why do we need to sit there and listen (unless it's the shtick, as it is for Ben Stein)? Why do I need to deplete my small funds for readers to bring in someone who can't — or refuses to — interpret their own work for the audience? This actually makes students less interested in literature.

Some people are blessed with booming voices (I only discovered I had one about 10 years ago), but, even without natural projection, all the markers of an evocative reading can and should be learned. Note: there's no single set of things one can do to be interesting, but dammit, at least do something.

Think of a variation on the problem: the poetry reader who spends five minutes introducing the two-minute poem, and then proceeds to read the poem like "poetry." Each line receives the same pauses and emphases, and the poet assumes some ridiculous voice of "poesy" learned from attending too many formal readings. I call this "Fuck. My. Mouth." poetry, as an acquaintance once described viewing a poetry reading at one of the big conferences where a woman read in this voice — staid and poetic — and kept ending her stanzas with "Fuck. My. Mouth." There may have been a hint of irony here between delivery and content, but my reporter notes that it primarily came across as the same old bullshit line.

What does this mean for promotion? Well, we live in a world of book trailers (and you have a great one for Slut Lullabies) and social-media savvy promotion. At their best, these mechanisms can highlight a new title; at their worst, they can become time-sucking gimmicks. There's a fine line, and the netiquette is always changing. When I started writing it was still a bit dicey to publish in online venues for official academic credit toward tenure. I have a good friend who is a few years older than me and who comes from an academic school where publishing should be very "selective." In other words, he publishes novel chapters or longer short stories in the "major" (yes, I know) journals — and thus, has published only a handful of pieces in the last 15 years. Now, he's a really interesting writer, but I think it is very hard to sustain a career — whatever than means — based in that mentality.

Think of it this way, the generation of young writers after us won't abide by any of the norms of the previous academically inflected notions of career. Think of the explosion of blogs — good ones like HTMLGIANT , or boingboing, or bigother (I'm on the latter), and the sheer mass of posts and material and information and position-takings occurring in these places, and on FB and Twitter, and wherever else.

I've recently come across a number of posts where people offer two reactions to this phenomenon. 1) Isn't it great that we have all of these ways of keeping up with the literary world — changing as quickly as it does, and 2) Shit. Damn. I am filled with anxiety every time I jack into the online literary community because it makes me feel so damn inadequate.

The normal response is probably somewhere in between, and you and I — both with families and jobs — may in fact simply be what many of these people online all day long will eventually become: people whose free time is almost non-existent and so who can participate only selectively in this world while the next set of young-uns spends all their time jacking stories directly into the brains of their subscribers in 2050.

The normal response is probably somewhere in between, and you and I — both with families and jobs — may in fact simply be what many of these people online all day long will eventually become: people whose free time is almost non-existent and so who can participate only selectively in this world while the next set of young-uns spends all their time jacking stories directly into the brains of their subscribers in 2050.

Back to performativity. Despite my reputation, as you put it above, and my own set of what I like to call provocations when reading (threading rope through the audience and having people pull me as I read, etc.), I am wary of the type of unaware self-promotion that is simply "brash" as a replacement for content, or that so uncritically practices performativity that the gimmick covers up for the lack of interesting material. I don't want to build new authorial temples.

For me, the most interesting writers are those whose work dovetails in effective ways with its presentation. Someone like Debra Di Blasi or Jaded Ibis comes to mind. You can count on Debra to present site-specific work, as she did at the first &NOW in 2004 at Notre Dame, organized by Steve Tomasula. There, she offered a scratch-and-sniff detective story without simply running a dry text through a wet mechanism.

This probably speaks to my bias for the "innovative" end of the indie literary spectrum in contemporary publishing (although I certainly love all sorts of novels and routinely teach things that would strike my own readers as retrograde realism.) The work &NOW cultivates is almost always that of writers whose work lends itself to interesting mechanisms of presentation. No doubt this could be done with any text — even Stephen King's latest, whatever that is — but the aesthetic of &NOW, which leans toward the conceptual, aims to create spaces for memorable experiences: both on the page and in the audience.

What's your take on readings? Do you really listen? Does your mind wander?

Frangello: I don't have a problem listening at readings if the work is good and is the kind of work I like. I mean, that sounds kind of trite and obvious, but I don't know how else to put it. There's less of a filter on readings than there is in terms of book publishing: just about anyone with a mic and a friend who owns a bar or works at a bookstore can have a reading, or be part of one, and you invariably hear a lot of material that is either very rough, not ready for publication yet, or that will... well, never be ready for publication. You also, if you work in publishing and attend a lot of readings, which I do, end up hearing a lot of writers who may be talented and have fans, but whose work is just not up your alley, for whom you are not the best audience. So readings can be challenging, yes. If I go to a bookstore, I'm not going to return home with a book that either: a) could never have gotten published in the first place or b) seems completely wrong for my tastes. But going to a reading on any given night, this is certainly what might be in store for me. That's the nature of live performance. I'd say on the up side that fiction readings are rarely as dismal as some other types of live performance can be, such as a painfully un-funny stand-up comic, or a horrifyingly bad band that hurts your ears. But live performance is always a risk.

This said, a good performer can sometimes make work come alive in a way that transcends what is possible on the page. I've heard Salman Rushdie read, for example, and when he's up there on the stage reading his work, I am mesmerized. Which may not sound surprising except that, though I am a bit embarrassed about it, I don't actually enjoy reading Rushdie. I find his work unbelievably dull on the page! Obviously many people worship him, but I'm just not one of them. Apparently, if he would only come over to my house and read his books aloud to me, I'd be his number one fan. This is the mark of a really good performer: someone who can seduce you with work you wouldn't like on the page. That's a rare feat.

Schneiderman: So do you select manuscripts for OV with any thought as to how the writer will promote the book? I believe you knew Zoe Zolbrod before taking Currency and I'm not sure if you knew Billy Lombardo personally, but as a publisher, how does all this stuff play into your selection process?

Schneiderman: So do you select manuscripts for OV with any thought as to how the writer will promote the book? I believe you knew Zoe Zolbrod before taking Currency and I'm not sure if you knew Billy Lombardo personally, but as a publisher, how does all this stuff play into your selection process?

Frangello: This is a really pertinent question for all publishers, but for indies most of all. I mean, all writers will do better if they are willing to, and understand how to, market their books, but if your book is coming out from Little, Brown or HarperCollins and you're a writer who is painfully shy, refuses to travel, has no time to guest blog, whatever, then theoretically your publisher, if they really, really believe in your book, can do things like take out ads in the New York Times or the New Yorker to spread the word. With a big enough marketing budget, a book written by a hermit can become an international bestseller. (To be clear, most books coming out of the corporate publishing arena have nothing resembling an unlimited budget, and in many cases the budget may not be much bigger than that of an indie, if the author isn't part of the big publisher's front list, or one of the few titles it's really chosen to champion to the hilt that season.) But with indies, no matter how much your publisher believes in you, those high-priced ads and payment to the chain stores for "hot" placement like on the display tables, those things are just not gonna happen. So the publisher and the writer both have got to be willing to work it in other ways.

Readings. Touring as much as you can, and networking with other writers and with readers and bloggers wherever you go. Guest-blogging. Podcasts. Interviews with anyone who wants to ask you a question. Facebook. Twitter. Marketing your book can become a full-time job, and it can offer a lot of exciting direct contact with one's audience, but this sort of thing does not appeal to all writers, and for some is not even possible.

I went in to Other Voices Books very idealistic and naïve about this sort of thing. I believed it was my job to pick and publish books I loved, and that the public and the media would simply "find" these books by some kind of artistic magic. This is not to say I didn't promote them, because of course I sent out tons of galleys and I myself talked and blogged about the books every chance I got. But I had underestimated the role of the author's own personality and platform in the equation. When you're a publisher and editor, your own network of friends and contacts can very quickly reach their "favor" threshold in terms of buying all the books you publish and turning out to every event you throw for an author. The writer needs to have her or his own network of people and a platform on which to connect with readers. If they don't have it going in, they need to have the personality, the energy, and the time to devote to building it, and the book needs to have an angle that makes that possible. For example, yes, like you mentioned, we just published a debut novel, Currency by Zoe Zolbrod. Zoe is a first-time writer, but she's been touring all over the country, and her novel takes place in southeast Asia in the backpacking community, so she's been working particularly hard making connections in the travel blogging networks, since there's a natural audience for her work there. But those people may not be super tuned-in to indie press fiction per se. I knew Zoe and knew she was capable of working this as hard as she could. I knew she was one of those people who, after someone meets her, they always end up coming back to me and saying, "She was amazing!" or "There's something about her!" and that "je ne sais quoi" factor, well, not everyone can have that, but it can be a tremendous asset.

Many Other Voices Books writers have come to us already with a "base" of people in the writing community who know them and to whom they can reach out, but certainly this has not been the case across the board. As a publisher, you want to take chances on new writers, but if a writer works 75 hours per week at a traditional day job, has small kids at home, is desperately short of money, and so things like touring, doing a lot of additional interviews or guest blogs, all of that, seems like a huge long shot... well, that can be daunting. And yet. As an editor and publisher who is also a writer — and who has a ton on my plate as well as small kids — I always want to give chances to writers who are busy, who have more to do than just promote their book 24/7, who are not, of course, necessarily independently wealthy! But they have to have the spirit, the drive to connect, to do as much as they humanly can within their parameters. Writers like Stephen Elliott, Joe Meno, and Steve Almond have really proven what competence, innovation, and dedication to self-marketing can achieve if you also have the talent to back it up. Some younger writers too, like Matt Bell, seem to be born with an innate sense of genius in terms of community-building that's really authentic and reciprocal. Some writers are gifted in this way — are naturals — and others find it absolutely painful and embarrassing. We all know that does not necessarily correspond, in either direction, to how talented an author is on the page. But, unfortunately, publishers do not want to publish writers who fall into the latter camp these days. Publishing has become a highly social endeavor.

Many Other Voices Books writers have come to us already with a "base" of people in the writing community who know them and to whom they can reach out, but certainly this has not been the case across the board. As a publisher, you want to take chances on new writers, but if a writer works 75 hours per week at a traditional day job, has small kids at home, is desperately short of money, and so things like touring, doing a lot of additional interviews or guest blogs, all of that, seems like a huge long shot... well, that can be daunting. And yet. As an editor and publisher who is also a writer — and who has a ton on my plate as well as small kids — I always want to give chances to writers who are busy, who have more to do than just promote their book 24/7, who are not, of course, necessarily independently wealthy! But they have to have the spirit, the drive to connect, to do as much as they humanly can within their parameters. Writers like Stephen Elliott, Joe Meno, and Steve Almond have really proven what competence, innovation, and dedication to self-marketing can achieve if you also have the talent to back it up. Some younger writers too, like Matt Bell, seem to be born with an innate sense of genius in terms of community-building that's really authentic and reciprocal. Some writers are gifted in this way — are naturals — and others find it absolutely painful and embarrassing. We all know that does not necessarily correspond, in either direction, to how talented an author is on the page. But, unfortunately, publishers do not want to publish writers who fall into the latter camp these days. Publishing has become a highly social endeavor.

I want to say for the record, too, that I think women writers are a little more challenged in this arena, not just because of the (still relevant) factors of women's lives changing post-children where hitting the road for months on end à la Meno or Elliott would be much less common for a woman writer with kids, but also just because of more subtle issues of how self-promotion (or even extremely vigorous sociability) may be perceived differently in women than in men. I don't mean this across the board or as a black-and-white absolute, but as a trend. I myself am pretty social, and I tour, and I'm a 42 year old mom of three, so I'm certainly not trying to go overboard with this point. But I think women have difficulty being as aggressive as men in this arena, or it may be less well received when they do work that angle. So there are realities that seem to be there, but that you have to look beyond or work beyond. I'm not, after all, going to only publish, say, single-and-childless male writers who come from money and can tour the world on their own dime! So you can be aware of the truths of this business, but also aware of working — as many writers and publishers are — to change some of those dynamics, and of still letting love for the work be the dominant issue.

But wait, Davis, after going off about gender and how it impacts the writerly life, I'm going to potentially backtrack and say that this stuff, while it does have something to do with gender in the ways I've discussed, maybe has a lot more to do with lifestyle choices the writer makes. You and I, unlike, actually, a lot of writers I know, have chosen to lead lifestyles that can seem, on one level, very counterintuitive to what writers are "supposed" to do, i.e., putting "the work" — our own writing — above everything else. By contrast, we both have kids (I have three, you have two), we both publish other writers as well as write our own work, we're both married to spouses who are not "artists," or in your case, not artists of the same stripe (your wife was a journalist at the Chicago Tribune and now in the Conservatory at Second City, so there are similarities.) And of course, like most writers these days, given economic realities, we also both teach — you actually chair an English department. Can you talk about the role your own writing plays in your busy life? How do you make time for it? Do you write daily? Weekly? How has parenting — or publishing, for that matter — changed your identity and your practice as a writer?

Schneiderman: Wow. This is the day to ask me that question. I've spent the last week in the wilds of central Pennsylvania cleaning out my father-in-law's house after his recent passing, and while I meant, each day, to get back to this conversation, the hours passed in a flurry of the absurd de-cluttering of ancient toolboxes, in heat-vision attics with oriental rugs covering rickety floorboards, and in a morass of electronic equipment with tangles of wiring for no less than 27 separate audio and video components in two different household sites.

This week was clearly a hyperbolic version of the un-literariness of my daily life, but the long days or even minutes of creative writing time are so few and far between for me these days as to be almost non-existent. I wrote most of Drain before my children came along, and those moments — transcribing tape-recorded dream notes into a 1951 Remington and then into the computer — seem like something out of Denton Welch's novel In Youth is Pleasure: With I Left My Grandfather's House. Not only am I chair of the English department at Lake Forest College, but I also direct &NOW Books and its parent, Lake Forest College Press, chair the American Studies Program, co-direct our reading series and the annual Lake Forest Literary Festival (March 24, 2011: John Waters!), and serve on a number of committees, all along with my regular teaching load of old and new courses, etc. Forget the two children and the busy home life, add in &NOW stuff, and the time to write my "own" work, let alone promote it, is basically negligible.

This week was clearly a hyperbolic version of the un-literariness of my daily life, but the long days or even minutes of creative writing time are so few and far between for me these days as to be almost non-existent. I wrote most of Drain before my children came along, and those moments — transcribing tape-recorded dream notes into a 1951 Remington and then into the computer — seem like something out of Denton Welch's novel In Youth is Pleasure: With I Left My Grandfather's House. Not only am I chair of the English department at Lake Forest College, but I also direct &NOW Books and its parent, Lake Forest College Press, chair the American Studies Program, co-direct our reading series and the annual Lake Forest Literary Festival (March 24, 2011: John Waters!), and serve on a number of committees, all along with my regular teaching load of old and new courses, etc. Forget the two children and the busy home life, add in &NOW stuff, and the time to write my "own" work, let alone promote it, is basically negligible.

(I'm always struck by the industriousness of young writers who recognize, as you say, the need to build an audience. We grew up without Twitter in five feet of snow that contained fallout from Three Mile Island, so we know what it's like to live a relatively disconnected decade in our 20s. This was probably good for us, in that I would have written much less in my relative youth if I had been even half as busy as I am now trying to keep up with readings that proliferate via social networking, etc.)

And yet, I still manage to write, but the forms have changed for me. I consider myself a novelist, even though I've published many short stories and smaller pieces. A good chunk of these are novel excerpts that I have reverse-engineered, but I've also discovered a second strand to my work that I consider to be a better home for shorter pieces, and I've been working to develop two mechanisms to make these shorter pieces happen. I hesitate to call this work "conceptual," but I suppose some of it might be labeled that, especially in opposition to the longer canvas of projects like Drain.

The first method is collaboration. I became aware of you from your Chiasmus Press book, My Sister's Continent when Chiasmus published my collaborative novel Abecedarium, written with Carlos Hernandez, in 2007. We wrote that book in 2.5 days in a flurry of close-quartered collaboration. From there, and although it took a few years to percolate, I began a project called Book. I call it "my Elton John duets record except I am not wearing a Donald Duck suit" and the manuscript (now making the rounds) consists of exactly that: collaborations with different writers, each generated by a machine or method specific to the collaboration. Lance Olsen and I sent dreams back and forth for a thematic piece. With Nick Mamatas, I responded to actual emails he had accumulated during his day job. I've been lucky enough to work with some fantastic writers on these: Blake Butler, Cris Mazza, Henry Mescaline, Stacey Levine, Mark Spitzer, Megan Milks, Jessica Berger, and my inimitable wife, Kelly Haramis. This has generated also some false starts, but some interesting longer collaborations, including in-progress projects with Rob Stephenson and a Choose Your Own Adventure novel with Trevor Dodge. For me, these projects are like playing multiple chess games at once and thus "easy" for me to squeeze in between other work.

The first method is collaboration. I became aware of you from your Chiasmus Press book, My Sister's Continent when Chiasmus published my collaborative novel Abecedarium, written with Carlos Hernandez, in 2007. We wrote that book in 2.5 days in a flurry of close-quartered collaboration. From there, and although it took a few years to percolate, I began a project called Book. I call it "my Elton John duets record except I am not wearing a Donald Duck suit" and the manuscript (now making the rounds) consists of exactly that: collaborations with different writers, each generated by a machine or method specific to the collaboration. Lance Olsen and I sent dreams back and forth for a thematic piece. With Nick Mamatas, I responded to actual emails he had accumulated during his day job. I've been lucky enough to work with some fantastic writers on these: Blake Butler, Cris Mazza, Henry Mescaline, Stacey Levine, Mark Spitzer, Megan Milks, Jessica Berger, and my inimitable wife, Kelly Haramis. This has generated also some false starts, but some interesting longer collaborations, including in-progress projects with Rob Stephenson and a Choose Your Own Adventure novel with Trevor Dodge. For me, these projects are like playing multiple chess games at once and thus "easy" for me to squeeze in between other work.

In addition, my next novel, blank: a novel, from Jaded Ibis, is exactly that, a largely blank novel of 200 or so pages that comes in three versions: 1) Kindle, 2) traditional, and 3) art book encased in plaster which you must break to reach the blank novel. A project called The Un-Death of the Author places my name on pre-copyright literary works, and post-copyright public domain and government documents. These take as much time and thinking as the longer novels (and an Un-Death manuscript is in the very slow works), but for some reason I think of these as puzzles that can be played out in a briefer creative space.

No doubt, my life conditions have led me to these methods. But don't think that just because I'm a lush, I write drunken characters. I abhor biographical criticism.

I am also aware that much of what I do as an appropriation artist is not to everyone's taste, conditioned as they are by complex notions of "literariness" and economics. The more economic success one might have as a so-called avant-garde artist, the less street cred. In this way, I am very lucky to have a home in the university system, which provides "cover," if you will, for my artistic explorations. I imagine that, were I a writer with a traditional "day job" and no university training, my aesthetics would have evolved quite differently.

So, this leads me to my question of institutionalization and contemporary writing. I am wary of the workshop model, not because I think it stands in opposition to some bullshit romantic notion of the writer, but because of its normative powers. I fought against my training in a creative MA and PhD program to some extent, or at least convinced myself that this was my stance, and yet so many of the writers in my sphere are academics. Obviously, many more have MFAs and other degrees and have not gone on to the dismal hiring slag known as the academy. You, too, if I recall, have an advanced degree. Yes, one can learn to write, but how does our massive system of advanced writing degrees affect what we do as publishers and the ways we promote our authors?

Frangello: Other Voices Books isn't affiliated with a university, and, other than attending the AWP conference, I don't feel like we move in particularly academic circles or are reliant upon the academy as anything resembling an exclusive audience, though sometimes, such as with anthologies with great classroom potential, we do market vigorously there.

But even though it's not necessarily related to Other Voices Books (or The Nervous Breakdown, which is even less academic in origin or following), still this question is extremely pertinent for almost all writers in the indie community, because the indie community has such strong overall ties with the academy. In some indie circles, questioning the concept of the MFA can be almost as loaded or taboo as talking about politics or religion can be in other circles. (Luckily unorthodox views on politics and religion are not terribly taboo in the indie world, which is one of the things I love about our world!) At a very basic level, so many of us teach for a living that to decry the inefficacy of MFA programs in terms of breeding "great" writers can smack of hypocrisy if we don't really examine what we're saying and unpack the meaning behind it . . .

Personally, I loved graduate school. So I'm not trying to say graduate school sucks or is a big scam. What I want to unpack is what graduate school is for — what it helps writers achieve or attain. In most cases it does not help people attain work that pays a viable living, nor does it, unless perhaps you go to Iowa, tend to really help you attain publication in any direct fashion. Further, I do not believe that what students attain is "learning how to be great — or really, really good — writers." Certainly an advanced degree can help you become a better writer than you were when you began. But what "better" means for any given individual covers a wide, wide range.

What MFA or other grad programs offer, quite genuinely, is time, space, and community. For my part, I chose a program that would pay me to teach while I was going to school, and that would waive my tuition. I come from a very blue-collar background and had no illusions about being able to really earn a living as a writer, so I would never have personally made the choice to go into debt for a writing degree. So for me, the situation was pretty win-win: I was being paid a small stipend to write, to teach intro workshops, and to sit in lit and writing classes with peers at a similar stage of their careers and interact intensely with them and with my professors about my craft and the craft of other writers. To put it mildly, this is a very enjoyable experience. I did not have a job outside of my university and I saw my writer-peers every day. I read all the time, virtually nonstop, a variety of work: student work, peer work, published (both cutting-edge and canonical) work, and when I was not reading I was writing or talking about writing. If you have any small measure of talent as a writer at all, surely this intense experience can benefit your own craft, while giving you a structure to generate a body of work. MFA and other programs are like writing retreats that last for several years. As a writer, there is not much to dislike about that lifestyle.

But it's extremely important to distinguish between something that "benefits" a writer's craft and something that can "make someone a great writer." The vast proliferation of advanced degree programs for writers these days virtually guarantees that the majority of students entering grad school for writing degrees will never actually become professional writers. There are a number of reasons for that. One is that a lot of people will give up and stop writing. More than half the people I know from grad school no longer write fiction at all; once full-time work or busy family lives make it genuinely hard to write — not everyone will push through that, which I know you and I can both sympathize with, even though we both do continue to engage in that struggle. But another basic reason is that some base-level amount of innate talent is simply necessary for success, no matter how one defines "success," and a lot of people who enter graduate writing programs do not possess that elusively requisite, innate amount. This is the controversial thing we are not supposed to say.

But look. No matter how many years — or how intensely — I studied basketball or physics, I would never be a professional basketball player or physicist. I simply am not wired that way. I could (maybe!) be taught a basic level of competence, whereas currently I have no competence in either of those fields whatsoever, but I could not be made truly good. The world of professional sports does not pretend it can make a Michael Jordan out of anyone who likes to throw a ball. PhD programs in physics will not even admit people who are not already demonstrating a certain degree of brilliance. Writing programs are not always this discriminating. We admit people based on some inkling of "promise," or on the concept that "every story is equally valuable" and every writer's voice equally important. It is hard to argue with this because writing is so personal, and so to dispute this claim can smack of saying that all people are not equally valuable or important. But what I dispute is this simplistic correlation. I used to be a therapist, and I believe strongly that all people are equally important and that all of their stories are equally valuable in life. I also believe that it is important for writers to tell diverse stories and to represent a wide array of human life and voices on the page. However, I do not believe that all people are equally equipped to tell/write their stories in literature, any more than that we are all equally equipped to make a slam dunk or do research on the earth's magnetosphere or perform surgery. And, as such, I believe too many students are misled, by admission into graduate writing programs (which are thought to be professional training grounds) into thinking they are "better" than they really are. To admit someone into a training program is to imply that they may someday find gainful employment and success within that field, and there are many MFA students out there for whom this is a clear impossibility. To say this aloud seems to be a form of treason in some circles, but for god's sake anyone who has ever sat through workshops for years on end knows that it is true. Each writer in the room benefits from the same instructor, the same peer feedback, but not each writer performs at a comparable level by a long shot. Some of this may be due to past educational discrepancies, and a great joy as a teacher is to find such students and help nurture them and give them the tools they need to emerge in their own rights. But often it's not that simple. We have all had students — middle-class students who are bright and have received solid educations — who are not very good writers; who just don't have it in them. To pretend this is untrue is just folly.

What you were saying in your question, Davis, is also important: that workshops and academia can encourage a kind of homogeny. I think this issue gets more play than the issue I discuss above because it's a kinder-and-gentler reason to dispute the proliferation of the MFA program. There's much validity to it, sure. The writer who goes home after receiving feedback in a workshop and then tries to incorporate every request or criticism into his or her work — to the point that the work no longer contains any of its original soul or vision — is a cliché indictment of writing programs because it can often be true. Remaining true to one's own vision can often seem indistinguishable from "stubbornly refusing to accept criticism", and it's very difficult for a young writer to tell the difference between what s/he should internalize and change vs. what defines his or her unique voice and style. What emerges can be bland and devoid of genuine risks. There can also start to be standard formulas among given programs in terms of what they believe stories "must" be like, or what works, and any deviation from that can be strongly discouraged. And yet crowd-pleasing is the death of literary fiction.

Problems of homogeneity and group-think can arise from any institutionalized atmosphere. However, I think the benefits of community and the writing lifestyle usually — for writers who do have some talent and a whole lot of drive — outweigh those risks. The homogeneity argument does not keep me up at night, because I simply know too many innovative and risk-taking writers, yourself included, who originated in such programs and managed to hold on to an individual vision. Group-think in writing programs is not much different from group-think in the publishing industry: it's always going to exist and it is always dangerous to anything that is truly new or innovative... and yet many things that go against its grain will always survive.