Guests

by Karen Abbott, December 31, 2010 9:39 AM

By far, the most fascinating aspect of researching and writing American Rose was untangling the complicated, intense, sadistic, funny, tragic, and heartbreaking relationship between Gypsy Rose Lee, her mother, Rose, and her sister, June. I spent countless hours at the Billy Rose Theatre Division of the New York Public Library (which houses Gypsy's archives) immersed in their correspondence, and often left feeling emotionally drained and physically ill. Rose would send one letter to Gypsy, begging forgiveness for all of her past transgressions, and, in the next, admonish her for being an "unnatural child" and leaving her mother behind; I could see where Rose had broken her pencil from pressing too hard on the paper. In the musical Gypsy, Rose — played on Broadway by Ethel Merman, Tyne Daly, Bernadette Peters, and, most recently, Patti LuPone — performs a wrenching number called "Rose's Turn" (which theater critic Ben Brantley called "a nervous breakdown set to music"), the lyrics bemoaning the fact that Gypsy archived the success that Rose had always craved; in the end, mother and daughter exit the stage together, arm-in-arm. Not so in real life. In the book, I write of Rose's and Gypsy's bond: Theirs is a primal connection that Gypsy is incapable of severing, parallel to love and just as deep but rotten at its root. It is a swooning, funhouse version of love, love concerned with appearances rather than intent, love both deprived and depraved, love that has to glimpse its distorted reflection in the mirror in order to exist at all. Here are excerpts from the best (and worst) of their letters: Rose to Gypsy, circa 1945: Dear Louise, I was so grateful today to be able to talk to you. I am so sorry for anything I have done to make you feel like you do about me. Now if I can do anything in the world to make you feel different about me I will be so glad and happy to do it. I need you and June to see now and then to make me feel like there is something for me to live for. I haven't a soul in the world to look to for happiness but you girls, and I have been trying so hard to do what is right in every way I can think of… Please Louise listen to your real self and forgive and forget everything that has separated us. Believe what I am writing and give me that one big chance again to make good in your heart. If you won't have me, Louise, I will be all alone. Love, Mother Rose to Gypsy, August 23, 1945: Dear Louise, I have waited to hear from you dear but no call. I sent you a telegram, maybe you didn't get it... I am going to give you back to God, Louise, for him to manage you and I. He will untangle this whole unhappy affair I know. In the mean time I am going to know that you will and must love me... Lots of love, Mother Rose to Gypsy ("Louise"), October 28, 1950: Dear Louise, I am writing to tell you I feel sorry for you, dear... It is difficult for me to believe that you could be so heartless and cruel to anyone and above all your own mother... Two daughters living in mansions, with everything and I can't get decent medical care from either one… God Louise it seems almost impossible that you girls could be so heartless... I wonder if you really are a communist Louise? God alone will surely punish you for your treatment to me… Love to you, Mother Rose to Gypsy, April 30, 1951: Dear Gypsy, you know, I have never before in my life felt like I do now... Living on One Hundred Dollars a month... Asking, pleading, begging to you in every form has been of no avail. I am satisfied now and know in my heart that you are absolutely heartless and unnatural, incapable of a feeling God gives. I thought every daughter gave some feeling for her mother. Now that I think back there is nothing in my life that should make either of you feel like you do. You made money your god and goal and that is all you ever cared about... Now the time has come that I feel in all justice to my very soul to let the outside world just know what kind of girls I brought into this world... My life with you two girls was anything but a happy one. Things you made me go through and endure in regards to all your stepping stones, to your getting where you were interested in getting — at any cost — must now be told to your faithful public that do not know you at all... You are wicked, selfish, cruel, unnatural and you must be made to realize the day must come for reckoning. With God's help, your punishment will come to you...I was your slave and colored maid for years and years... Now I must give you your lesson like a mother should a child...You may have your papers, as you say, bribed to tell your stories but there is a way — and I intend to use it as soon as I am able. There is nothing of your life I don't intend to tell of the part I had to play with it. And after all was over and you got what you wanted, you flung me away and did not want to bother with me. I had had my youth. I pity you. [signed] Your Mother Gypsy to Rose, May 4, 1951: Dear Mother, a registered letter addressed to me, supposedly from you, arrived in New York and was forwarded to me here in Toronto... It is inconceivable that you would even think of sending such a letter after the recent visit I had with you at the hospital, all on such a friendly level and after the letter you sent me the other day which expressed nothing but gratitude and confidence... Mother, you own three houses, at least five acres of land, a good car and a paid up annuity, which gives you an income of over a hundred a month that I know of, plus whatever else you have... And now comes the letter of the 30th. As I said before, I cannot believe you sent it except for the resemblance that it has to so many of your previous letters and threats. This letter, as the others, is in the nature of blackmail, and I am sick and tired of such threats. There is nothing about my life which cannot be made entirely public... If you did not write or send the letter, I will some day show it to you. Yours, [signed] Gypsy Telegram from Gypsy to Rose, undated: Mrs. Rose E. HovickI have no desire to repeat last year's scenes which are too fresh in my memory STOP your so-called loneliness is of your own choice STOP if you want to go Seattle go direct STOP we just don't see eye to eye and that is final. Louise Hovick Gypsy to June, 1952: Dear June: I hate like hell to have to write you this letter... it's so awful. Mother has cancer of the rectum... they've been giving her blood transfusions and have already postponed the operation. Some drunken lesbian is causing a lot of trouble with the newspapers... But even if she were a total stranger she's in great pain and with an operation like this the chances are fifty fifty... Between the newspapers, the drunken bitch, and the general horror of it all I'm almost out of my mind. Please let me hear from you as soon as you can make it. Love, Gypsy Eighteen years later, when Gypsy was dyin

|

Guests

by Karen Abbott, December 30, 2010 10:35 AM

Irving Wexler was a poor kid from the slums of the Lower East Side, so skilled at filching wallets from pockets it was as if they were covered with wax; hence the nickname "Waxey." He picked "Gordon" as a surname. Waxey met Arnold Rothstein in the days before Prohibition, working in the garment district as a labor enforcer. As anyone familiar with Roaring Twenties history (or the HBO series Boardwalk Empire) knows, Rothstein was a premiere bootlegger, mastermind behind the rigged 1919 World Series, inspiration for The Great Gatsby's Meyer Wolfsheim, and capable of intimating a murder threat through the slightest quiver of an eyebrow.  Waxey became part of his circle, eventually working alongside fellow gangsters Lucky Luciano and Meyer Lansky, and Rothstein became the master of New York City's illegal liquor trade — the largest operation in the country, with an estimated 32,000 speakeasies. At the height of Rothstein's operation, eighty percent of the liquor distilled in Canada found its way to the United States, and the Bahamas' exportation of whiskey increased 425 fold. Determined to take over a number of breweries in New Jersey, Waxey began warring with the Irish gang that controlled them, murdering them one by one. The breweries were technically legal since they manufactured "near beer"; their authentic stuff was produced and transported to bottling and barreling facilities via an intricate, elaborate system of underground pipes. During one raid, federal authorities discovered a 6,000-foot beer pipeline running through the Yonkers sewer system. In New York, Waxey's web of contacts set up neighborhood cordial shops with "importer" or "broker" plates nailed to the door, a clear signal that they were "in the know." To pick up business, these clever proprietors also slipped flyers under windshields and under apartment doors, offered free samples and home delivery, took telephone orders, and urged customers to "ask for anything you may not find" on the menu. For the weekend warriors, steamship lines operating out of New York introduced cruises with no destination at all but the "freedom of the seas." In 1931, when Waxey met Gypsy Rose Lee in a Manhattan speakeasy, he was 43 years old and married, with three children. He kept his family in a 10-room, four-bath apartment at 590 West End Avenue (paying $6,000 per year in rent at a time the average annual salary was $1,850) and decorated with the help of professionals, including a woodsmith who custom-built a $2,200 bookcase. Five servants catered to their every whim. His children attended private schools, took daily horseback riding lessons in Central Park, and spent summers at their house in Bradley Beach, NJ. He owned three cars, bought $10 pairs of underwear by the dozen, and stocked his closets with $225 suits tailor-made for him by the same haberdasher who outfitted Al Capone. In 1930, Waxey made nearly $1.5 million and paid the United States government just $10.76 in taxes. Gypsy was just 20 years old at the time and worried obsessively about money — "Everything's going out," her mother, Rose, warned her daily, "and nothing's coming in." She had just scored her first big break in burlesque, working as a headliner for Minsky's Republic on Broadway, but the days of starving on the old vaudeville circuit, eating dog food just to stay alive, were still fresh in her mind. This basement club, along a dingy stretch of Eighth Avenue, was the first speakeasy she'd ever seen. Waxey Gordon took a seat at a nearby table, joined by four bodyguards wearing green fedoras slouched down, shadowing their faces. She knew Waxey was rich and powerful and, most of all, an opportunity, and for once she bided her time, waiting for opportunity to approach her instead of rushing to seize it first. Gypsy watched Waxey Gordon watching her, his eyes fixed with purpose as he summoned a waiter and whispered in his ear. He watched as the waiter approached her table, hoisting four bottles of champagne high in the air, and as he set them down, saying, crisply, "Compliments of Mr. W." Waxey watched Gypsy sip the champagne and noted the realization pass across her face; accepting his gift was as much an invitation as a courtesy, an implicit agreement that he would open doors she'd be obliged to step through, locking them tight behind her, no matter what she might find on the other side. "Thank you for the champagne," she told Waxey when he strode over to her table, the bodyguards lined up like ducklings behind him. He nodded and said, "You can't tell when you'll run into me again," although she did, indirectly, on the phone the following morning. "No names," a strange voice barked at Gypsy. "I'm calling for the friend you met last night." Mr. Gordon, the voice continued, wanted her to visit a certain dentist at 49th and Broadway. She had an appointment the following morning to get her teeth straightened. The new caps were beautiful, Gypsy thought, and looked like real teeth — no matter that she could no longer eat corn on the cob, or that they felt like pins lodged deep into her gums. Waxey Gordon was another member of her new world, and she was still learning its language, cracking its code. When Waxey told her to keep her new teeth "brushed good," she did, meticulously and obsessively. When he invited her to perform at a benefit for the inmates of Comstock Prison, at which Broadway impresario Florenz Ziegfeld was expected to be a guest, she signed on right away (although her appearance was cancelled when wardens worried she might corrupt prisoners' morals). When Waxey told her he wanted to give her a dining room set for her new home, she could not have been more thankful for the gesture. When Waxey wanted her to appear on his arm or in his bed she obliged, learning to take more than she gave without anyone sensing the difference. "She was very involved in the underworld," Gypsy's sister, June Havoc, told me. "She was one of their pets, just like Sinatra… it guaranteed things, the kind of things she wanted." June happened to be in New York the night Waxey Gordon's stolen furniture was scheduled for delivery. She arrived at Gypsy's house in Queens and found her mother wrapped in a bathrobe, popcorn in hand, watching a "blue" movie, a quaint old term for soft-core porn. Gypsy was upstairs primping, brushing her new teeth. At 4 a.m., the doorbell rang, and a team of burly men lugged in a long, carved-oak table and 30 ornate matching chairs, the grandest dining set any of them had ever seen. Waxey Gordon followed and turned toward the stairs, waiting. Gypsy descended, pointing her toes and accentuating each step, an entrance meant for Waxey Gordon alone. "I'm sorry I took so long," she told Waxey, and then directed his men to the dining room. Rose turned to Waxey, looking at him through lowered eyes. She smiled and spoke softly: "Well, son," she said, "I am the mother of Gypsy Rose Lee." "Pleased to meet you," Waxey said. She pointed a finger at June. "And this is my baby. She used to be somebody, too." When Waxey left, Gypsy said goodbye, calling him "Mr. Gordon" and shaking his hand. He called her "kid." Rose sighed and said, "Class. Class. No pretense, just honest

|

Guests

by Karen Abbott, December 29, 2010 11:47 AM

Radio and "talkies" both played a role in vaudeville's demise, but the last, crushing blow was the onset of the Great Depression. Rose Hovick had always reassured her daughters that vaudeville would survive because "there was no substitute for flesh," and the axiom was true — but it applied to burlesque, not vaudeville. Vaudeville, with its sense of sunny, mindless optimism, no longer spoke to the country's mood. Burlesque did, loudly and directly. The Depression affected female workers to the same degree as men, and thousands of them, out of work and other ideas, applied at burlesque houses across the country: former stenographers and seamstresses and clerks, wives whose husbands had lost their jobs, mothers with children to support, vaudevillians who finally acknowledged the end of the line. Compared to other forms of show business — compared to any business — burlesque enjoyed a low rate of unemployment, and 75% of performers had no stage experience at all. Pretty girls were finally available at burlesque wages, and the supply equaled the demand. Gypsy never spoke much about 1929, that limbo period after June fled but before she really became Gypsy Rose Lee. Throughout 1929 she was still Louise Hovick, the awkward girl with brains but no talent, and she and her mother were floundering. She subsisted on sardines and dog food and gigs at burlesque houses where men held newspapers over their laps, masturbating to every bump and grind. She was forced to do things against her will, and decided the only way to "climb out of the slime," as June later put it, was to become someone else. By the time a producer named Billy Minsky discovered her in Newark, New Jersey, the transformation had begun. He noticed she was shy — ironically, most stripteasers were — but this girl had a way of teasing her own trepidation, mocking it, turning it out like the fingers of a glove. Stripteasers rarely spoke two syllables on stage, but this one couldn't not talk, as if each twirl of the wrists, every stride of those legs, deserved narration. She wielded a powder puff on a stick and swiveled her strangely exquisite neck like a periscope, seeking a secret hidden somewhere in the crowd. "Darling! Sweetheart!" she exclaimed. "Where have you been all my life?" At the finish, when other "slingers" invited the audience to come closer, Gypsy pulled away and looked down, as if shocked to see so much of her own skin. Backing up against the curtain, standing tall and regal and unobtainable, she gripped its velvet edge and made herself a cape. "And suddenly," she whispered, like the end to a fairy tale, "I take the last… thing… off!" She hurled her dress in the air, a vivid velvet flag of surrender. Billy knew he had never seen anything like her, and never would again.  At Minsky's Burlesque in New York City, Billy dedicated each new season to a girl, and 1931 belonged to Gypsy (although he immediately disliked her meddlesome, nitpicky mother, and thought her "river did not run out to the sea"). She wasn't "hot" like Georgia Sothern, whose strip was akin to an epileptic seizure, nor overt and busty like Carrie Finnell, who affixed fish swivels to her pasties — contraptions that allowed her to pinwheel her tassels in any direction, from any position, at any speed. Gypsy was an original, a Dorothy Parker in a G-string, savvy enough to perform a burlesque of burlesque, to make performance out of desire. "Seven minutes of sheer art," Billy told her, and the rest of New York agreed with him. She managed to be at once highbrow and low. One night, she attended an opening at the Met wearing a full length cape made entirely of orchids; the next, she invited her burlesque friends to her dressing room, where she performed very naughty tricks with her pet monkey. She was adored by everyone: longshoremen and literati, Columbia professors and New York politicians, members of the Algonquin Round Table and the city's most formidable gangsters — one of whom decided that he, too, should have a hand in creating Gypsy Rose

|

Guests

by Karen Abbott, December 28, 2010 10:36 AM

One of the most rewarding parts of writing historical nonfiction is finding primary sources, first-hand details, and anecdotes that help illuminate the past. Early on in my research for American Rose, I was fortunate to visit Gypsy Rose Lee's sister, the actress June Havoc, who died in March at the age of 96. She was bedridden, and the legs that had once danced on stages across the country were now motionless, two nearly imperceptible bumps tucked beneath crisp white sheets. But her memories were sharp; talking with her was like being magically transported back to the Roaring Twenties (I've posted some audio clips of our interviews on my website). June spoke passionately about vaudeville, the premiere form of entertainment during the 1920s, and it struck me that vaudeville was the reality television of that era — the one difference being that, back then, entirely average people had to work hard at being famous. Many vaudevillians possessed talents invented rather than innate, and with relentless practice and a clever marketing scheme they were able to make a fortune. Some of my favorite vaudeville luminaries include: - Hadji Ali, otherwise known as The Amazing Regurgitator, who, for his grand finale, had his assistant erect a small metal castle onstage while he drank a gallon of water followed by a pint of kerosene. To the accompaniment of a drum roll, The Amazing Regurgitator ejected the kerosene in a six-foot arc and ignited the tiny castle in flames. As the flames grew he then ejected the gallon of water and extinguished the fire (check out a video of Hadji Ali).

- The Human Fish ate a banana, played a trombone, and read a newspaper while submerged in a tank of water, while Alonzo The Miracle Man lit and smoked a cigarette, brushed his teeth, combed his hair, and buttoned his shirt — miracles since he had been born without arms.

- One man had a "cat piano," an act featuring live cats in wire cages that meowed Gregorio Allegri's Miserere when their tails were pulled (in reality, the performer yanked on artificial tails and did all the meowing himself).

- A woman called Sober Sue stood next to a sign that read: "You can't make her laugh." The theater manager posted a $1,000 reward and several of the best comics of the day tried, but all failed. When her engagement ended, it was discovered that it was physically impossible for Sober Sue to laugh because her facial muscles were paralyzed.

- Lady Alice was an old dowager who wore elegant beaded gowns and performed with rats. The runt settled on the crown of her head, a miniature kazoo clenched between teeth like grains of rice. He breathed a tuneless harmony while the rest of the litter began a slow parade across Lady Alice's outstretched arms, marching from the tip of one middle finger to the other. One day she revealed her secret: a trail of Cream of Wheat slathered on her neck and shoulders.

June, however, did have true talent — the ability to spin on her toes en pointe, ballerina-style, by age three. Her mother, Rose, immediately created a vaudeville act with June as the star and Gypsy and several boys in supporting roles. The act was called "Dainty June and Her Newsboy Songsters" (Gypsy played the part of a newsboy). One of their numbers featured a dancing cow. Gypsy said June always made her work the back end of the cow, but June disputed this claim. She told me: "Gypsy couldn't dance that well." From 1923 to 1927, Dainty June was one of the most popular vaudeville acts in the country, often earning $2,500 per contract (about $32,000 in today's dollars). But radio and film began luring vaudeville audiences away. The 10-minute "flickers" that had once rounded out a vaudeville bill became the main attraction, and numerous major vaudevillians — including Charlie Chaplin, W. C. Fields, Harry Houdini, and Rudolph Valentino — made forays into film. In 1927, Warner Bros. released The Jazz Singer, the first feature-length "talkie," starring erstwhile vaudevillian Al Jolson. It was the best-selling film of the year, and signaled another major blow to vaudeville. By then June and Gypsy had outgrown their act, both physically and emotionally — although their mother insisted that nothing had changed. In December 1928, June fled in the middle of the night, and the newsboy songsters quit and went home. It was now up to Gypsy to carry the act, although she'd never had any talent at all.

|

Guests

by Karen Abbott, December 27, 2010 2:45 PM

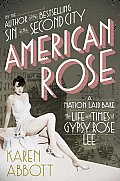

My 92-year-old grandmother, without fail, gives the best gifts: her winning poker strategy, authentic cloche hats, and stories that are always more interesting than fiction. When she told me about a great aunt who vanished in Chicago in 1905, I began researching that city and time period and discovered a world-famous brothel called the Everleigh Club, which became the subject of my first book, Sin in the Second City. Shortly before my publication date, and fishing for a new topic, I asked her about growing up during the Great Depression. She relayed a tale about a cousin who saw Gypsy Rose Lee perform around 1935. "She took a full 15 minutes to peel off a single glove," the cousin reported, "and she was so damn good at it I would've gladly given her 15 more." So this story got me thinking: who was Gypsy Rose Lee? I spent the next three years researching the answer, research that encompassed not only the Great Depression, but also the Roaring Twenties, prohibition, and two world wars. I discovered that Gypsy was a strutting, bawdy, erudite conundrum, adored by everyone but known by few; Life magazine called her "the only woman with a public body and a private mind, both equally exciting." Here are some of my most intriguing findings about Gypsy's life and times: - Gypsy was born Rose Louise Hovick, 100 years ago this January, during a snowstorm in West Seattle. She was called Louise for short and had a caul over her face, which she took to mean she had a gift for seeing the future. When she was a kid on the vaudeville circuit, working in her sister's act, she spent her downtime telling fortunes and reading tea leaves. One day she had a vision about a boy in the act — she saw a terrible car accident in which he was decapitated. This vision came true just a few weeks later, and she never read tea leaves again.

- Gypsy's parents divorced when she was three, and her mother, Rose, conditioned her to be wary of men — and also how to use them. "Men," she warned, "will take everything they can get and give as little as possible in return… God cursed them by adding an ornament. Every time they so much as think of a woman, it grows." Later, Rose would date women exclusively, and operate a lesbian boardinghouse in upstate New York. During a party, one of Rose's lovers reportedly made a pass at Gypsy — and ended up with a bullet in her head.

- In Gypsy the musical, Gypsy's success is presented as a part fluke, part the inevitable result of her mother's ruthless drive. But Gypsy herself was just as ambitious and calculating. After the stock market crash, when Gypsy subsisted on dog food and likely resorted to prostitution, she decided she would make a delicate, unclean break from her past, leaving the girl named Louise Hovick behind for good.

- Gypsy the person had a conflicted, tortured relationship with Gypsy Rose Lee the creation. For all of Gypsy's mental fortitude and steely nerve, she was physically weak and oddly susceptible to illness. "The body reacted," Gypsy's sister, June Havoc, told me, "because the soul protested." Taking just one aspirin could upset her stomach, and she suffered from severe ulcers that made her vomit blood. She adored her creation because it gave her the things she'd always wanted — fame, money, security — but she loathed its limitations, either real or perceived. She lived in an exquisite trap she herself had set.

- Gypsy was desperate to be taken seriously as a writer and intellectual. She wrote essays for the New Yorker, a play that was produced on Broadway, two novels, and a memoir. While living at an artists' colony in Brooklyn, working on her first novel, Gypsy was rumored to have had a fling with writer Carson McCullers. Each night Gypsy would feed Carson homemade apple strudel and then they'd snuggle in Gypsy's bed. She also became good friends with William Saroyan, even though she was jealous of his talent. "If I have night lunch with a smarty pants like Saroyan," Gypsy once confessed, "I want to spit on my whole damned manuscript."

- If Lady Gaga and Dorothy Parker had a secret love child, it would've been Gypsy Rose Lee. The woman knew how to make a dramatic entrance. On opening nights at the Met she would arrive in a long black limousine and step out wearing a full-length cape made entirely of orchids. She cultivated this image as a grand dame, but backstage, in her dressing room at Minsky's Burlesque, she invited her fellow performers to come watch her perform some very naughty tricks with her pet monkey.

- During World War II, Gypsy was immensely popular with soldiers. In 1943, she embarked on a tour and performed at 40 army and navy posts throughout the country. Soldiers named a stripped-down model of the Curtiss P-40L fighter aircraft the Gypsy Rose Lee. By the end of the war, 10 regiments had named her their "sweetheart." During the Vietnam War, she entertained troops in southeast Asia. By this time she was in her 50s, and jokingly said she was "sort of like a sexy grandmother."

- Eleanor Roosevelt was one of her biggest fans. On the opening night of Gypsy in 1959, the former First Lady sent Gypsy a telegram that read: "May your bare ass always be shining."

- When Gypsy was diagnosed with lung cancer and began radiation, she looked around at the other patients and told her son, "You know, when I look at all these people I can't bring myself to berate God for giving me such a horrible disease. I've had three wonderful lives, and these poor sons-a-bitches haven't even lived once."

More about Gypsy's three wonderful lives

|

Guests

by Karen Abbott, July 20, 2007 12:14 PM

I'm thoroughly enjoying the brouhaha over the " D.C. Madam" ? the Everleigh sisters' clients were much more savvy and discreet! ? and it brings to mind another fascinating (albeit totally unrelated) political sex scandal from a century ago. In the last quarter of the 19th century, a New York City politician by the name of Murray Hall rose through the ranks of Tammany. He was a member of the prestigious Iroquois Club and a personal friend of State Senator Barney Martin. He was a celebrated bon vivant, a womanizer and a brawler. He was the Captain of his election district and held court in an office on Sixth Avenue, between 17th and 18th Streets, where colleagues would often stop by after hours to share cigars and whiskey. He had been married twice and was raising a lovely young daughter. In January 1901, when Murray Hall died, it was discovered he was also a woman. Hall's fellow Tammany brothers were shocked at their friend's true gender. They marveled that she was able to "pass" so successfully for more than twenty-five years. "Why he had several run-ins when he and I were opposing Captains," one acquaintance told the New York Times. "He'd try to influence my friends to vote against the regular organization ticket and he'd spend money and do all sorts of things to get votes. A woman? Why, he'd line up to the bar and take his whisky like any veteran, and didn't make faces over it, either. If he was a woman he ought to have been born a man, for he lived and looked like one." Hall's death was particularly tragic; the parts of herself she most loathed were what ultimately killed her. She had breast cancer for several years, which she tried to self-treat with advice from books about surgery and medicine. The cancer, reported the Times, "had eaten its way almost to her heart." Not much is known about Murray Hall or her relatives. Even her adopted daughter, Minnie, was unaware that her gruff, hard-drinking father was actually a woman. I wish she had left a diary or some other clues that could help bring her back to life. Speaking of which, the most gratifying part of my tour has been meeting readers who have a personal connection to the Everleigh sisters or other characters in my book (although I wish I'd found them two years ago, while I was writing!). A woman at one of my readings told me Michael "Hinky Dink" Kenna was her uncle, and she showed me a check he endorsed in 1929. An elderly man related the story of his grandfather, who, as a young man, often saw the Everleigh sisters taking an afternoon walk through the Loop. Dressed in fine gowns and gaudy tangles of jewelry, they sisters waited outside the phone company and discreetly dispensed business cards to the young female operators as they left the building. These girls, it was understood, were well educated and refined, and could be transformed into proper Everleigh "butterflies" should they ever seek a career change. "I suppose," one man in the audience joked, "that's where the term 'call girl' comes from." But the most exciting discovery happened last night. A woman told me her aunt was hired by the Everleigh sisters to transcribe Minna's novel, Poets, Prophets and Gods, which I mention in Sin in the Second City. She has a scrapbook full of original letters and photographs. Her family members were in attendance when the Everleigh Club's lavish furnishings were auctioned off, and they won several pieces (I told her I'd take out a second mortgage to buy any of them, which I'm sure would just thrill my husband). We plan to get together before I leave Chicago so she can tell me all the stories I've never heard. Finally, here's a picture of Rick Kogan (see yesterday's post about Mr. Chicago) and my 89-year-old grandmother. I think they might elope. Thanks so much to Powell's for having me, and for reading. I'll close with Minna's sage advice for her prostitutes, which is certainly worthy advice for us all: "Give, but give interestingly and with mystery." ÷ ÷ ÷ Karen Abbott worked as a journalist on the staffs of Philadelphia magazine and Philadelphia Weekly, and has written for Salon.com and other publications. A native of Philadelphia, she now lives with her husband in Atlanta, where she's at work on her next book. Visit her online at

|

Guests

by Karen Abbott, July 19, 2007 1:22 PM

I'm a gambling girl by nature, but for the first time yesterday I was thrilled to lose a bet. Rick Kogan, a Chicago Tribune reporter, local legend, and very dear friend, bet me that I would hit the New York Times bestseller list. If he won, I'd have to fly him down to Atlanta and treat him to an all-expenses-paid visit to the city. If I won, he'd do the same for me in Chicago. I agreed, and told him he'd had one too many bourbons. Yesterday afternoon, my cell phone rang, and I literally tripped over a mound of shoes to get to it (I'm also an incurable slob). My editor's name was on the caller I.D. Lying on my hotel room floor, dripping wet in my towel, I heard her say two words: number seventeen. The first person I called when we hung up was Rick Kogan. I first met Rick in January. If you're going to write about Chicago, Rick Kogan is the man to know. He's synonymous with the city, as ubiquitous as the rattle of the El and the scent of deep dish pizza, and if you respect Chicago's stories and try to tell them with care, he'll be your biggest advocate. So on one brutally cold day last winter, he, my editor, and I had lunch, and happened to walk by the famous Billy Goat Tavern on our way out. My editor had to rush to get a plane back to New York, and Rick asked me if I wanted to stop in for a quick drink. Later on, he told me the proposition was a test to see if I was the kind of girl who would drink at the Billy Goat at two in the afternoon. Turns out, I'm that kind of girl.  Rick is sort of the Bard of the Billy Goat, having written a book about the place that reads like an extended ballad. ("A tavern is never as quiet as it seems," it begins. "It is filled with echoes and memories, of conversations and laughter, of faces and fights, and here there are 40 years' worth hanging heavy in the stale air and making time matter not at all.") He ordered himself a bourbon and me a beer, and we made small talk until he noticed that my cell phone wouldn't stop ringing. Rick is sort of the Bard of the Billy Goat, having written a book about the place that reads like an extended ballad. ("A tavern is never as quiet as it seems," it begins. "It is filled with echoes and memories, of conversations and laughter, of faces and fights, and here there are 40 years' worth hanging heavy in the stale air and making time matter not at all.") He ordered himself a bourbon and me a beer, and we made small talk until he noticed that my cell phone wouldn't stop ringing.

"What the @*#& is up with your phone?" he asked. "It's my birthday," I answered. We began doing shots. Rick loves to imitate my phone call the next morning: "Um, Mr. Kogan? This is Karen Abbott ? you met me yesterday... I just wanted to make sure you had the galley I left with you. If it somehow got lost, I apologize and I'll make sure you get another one right away. Thanks so much for lunch, and for the um... drinks... and I look forward to speaking with you soon." Sin in the Second City was a quiet, modest acquisition for Random House. I had a very modest advance (below minimum wage, if you calculated by hours of work) and in the beginning no one expected much, if anything, from my book. Rick Kogan swooped into my life and changed that. There's no way to adequately repay him, but when he comes to Atlanta, the shots are on me. ÷ ÷ ÷ Karen Abbott worked as a journalist on the staffs of Philadelphia magazine and Philadelphia Weekly, and has written for Salon.com and other publications. A native of Philadelphia, she now lives with her husband in Atlanta, where she's at work on her next book. Visit her online at

|

Guests

by Karen Abbott, July 18, 2007 10:13 AM

My mother-in-law, Sandy, passed the heirlooms to me one at a time: Antique china. A mink stole from Marshall Field's. A flawless emerald cut diamond engagement ring that looked exactly like my own, but several carats larger ? a coincidence neither I nor my husband was aware of when he proposed. Sandy had no use for them, but her mother wouldn't have wanted such treasures wrapped in boxes, wasted and unseen. Pretty things belonged to her mother in a way Sandy, an adopted daughter, never had. Martha Purnell had always been her own prettiest thing, and she collected the artifacts of her beauty as if its value, too, would appreciate over time. Every mention of her name in the society pages of the Chicago Tribune was clipped and pressed between plastic pages. "Representative Beauty" of Northwestern University. Chicago's Summer Queen of 1936, sent as a special envoy to the Texas Centennial celebration. A letter from Universal Studios seeking pictures of Martha "in a bathing suit... one that would show your figure to its best advantage." The papers printed news of her engagement to an insurance executive, detailed the showers at her Glenview mansion, and showcased her formal wedding portrait, the bouquet of lilies blooming wider than her hips. When the couple decided to adopt three children, all from different families, the photographers captured Sandy and her older sister, Marilyn, tottering through gardens and painting Easter eggs, and Martha hoisting the baby, Jeff, pressing her sculpted cheek against his as the shutters clicked once again. The Christmas after Martha, my husband's grandmother, died, Sandy copied each clipping and made a duplicate scrapbook for me. "Mother would have wanted you to see her this way," she explained when I unwrapped the gift. She asked for a hug ? they are, along with stuffed bears and Longaberger baskets, her own favorite collectible ? and sat next to me while I turned the pages. "She was a beautiful, elegant woman," Sandy said, "but I grew up feeling that I was not what she wanted." She dropped a finger to an image of Martha's mouth and pressed, as if the force of her touch could quiet her mother's still-familiar words. Since I'd known her, Sandy shared fragments of her mother over time, carefully parceled anecdotes about misunderstandings and disappointments and rejections. I witnessed a chapter myself, during my first and only meeting with Martha, over lunch at her retirement community in Florida. I noticed the way her face ? still lovely in its eightieth year ? changed, shifted into poses dark and unflattering, whenever she regarded her middle child. I saw how she stiffened inside Sandy's zealous hugs. I could sense there were thoughts she managed to leave unspoken. The problem, Sandy decided later, was that she came from "commoners" ? a lineage she never explored ? and was unable to adapt to the privileged life Martha wished to give them. She wasn't graceful and thin like her sister Marilyn; Sandy's figure couldn't mimic the model genes Martha hadn't passed on. She laughed too loud and too often and never retreated to the bathroom, the way mother had taught her, when she needed to cry. It became clear, over the years ? after her parents retired and moved south, after sister Marilyn died of cancer, after her father, once a booming, forceful presence, finally succumbed to a stroke ? that the only way Sandy could please her mother was to help Jeff, always the favorite child, and the most troubled. He crashed his car, served time for drunk driving, lost his license, lost apartments, lost all his teeth. Sandy refused to enable her brother and declined his requests for my husband's and my phone number, knowing each rejection of Jeff only pushed Martha further away. Her mother returned every gift Sandy sent her, but bought her son another car, and he crashed that, too. He moved into his mother's Florida condo, and his ferocious rages sent Martha into hiding for days behind the locked door of her bedroom, waiting for quiet to resume. It did, finally, one summer morning. A neighbor reported a foul odor outside Martha's apartment, and Sandy got the call from the coroner. Her brother's body had been found beneath a mattress in his bedroom. Martha was okay, albeit scared and confused. She had to move into a local hospital because her home was uninhabitable. Jeff had been dead for a week, maybe more, but trauma and old age had eroded her mother's sense of smell. Sandy drove from her home in Hillsboro, Wisconsin to Florida. The nurse on duty pointed down the corridor to a room. Sandy peeked in, and saw a woman with a large behind. "That's not my mom," she told the nurse, and tried the next room, where a tiny form lay, barely registering beneath the covers. Martha, without a doubt. Sandy had prayed about what to say, and hoped her mouth would be able to deliver the words God had given her: "I love you, mom, and I want to bring you home with me to live." Martha sighed. "Like going straight to hell," she answered. But it was decided. At nine in the morning, Sandy took her mother to get her hair set and styled. Afterward they began the long journey north, the car bulging with silence until Martha grasped Sandy's shoulder. "I've really been mean to you," she said. "Yes, you have, Mother," Sandy answered, and her only regret was that she didn't add "all of my life." Sandy's house was big enough for both of them to hide. She gave up her cat to accommodate her mother's allergies and forced her to eat breakfast every morning. When Martha's life became too elaborate a production for them to handle alone, Sandy moved her to a nursing home up the street. On the admittance form, the 87-year-old wrote "model" next to her name. During our most recent visit, five years after Martha's death, Sandy noticed I was wearing the identical rings ? one from her mother, one from her son ? stacked along my finger. I know she feels strangly guilty that her son and mother were never close; the rift between Sandy and Martha was one more thing bequeathed to the next generation. She asked for a hug, then sat down next to me. She visited her mother, Sandy said, two days before the end. Martha was in a wheelchair, head resting on the knob of her shoulder. Her knitted fingers made a translucent bird's nest in her lap. Sandy talked to her for an hour, and when she ran out of words Martha's arms lifted skyward, a fluid gesture that came from someplace outside of her. The lids closed thinly over her eyes. She held that pose for a good minute, Sandy remembered, and then her mother spoke. "I really do love you," she said, and I understood this was the last piece of her legacy that Sandy would pass on. ÷ ÷ ÷ Karen Abbott worked as a journalist on the staffs of Philadelphia magazine and Philadelphia Weekly, and has written for Salon.com and other publications. A native of Philadelphia, she now lives with her husband in Atlanta, where she's at work on her next book. Visit her online at

|

Guests

by Karen Abbott, July 17, 2007 11:05 AM

A few of my favorite Chicago tales: My friend Roberta (see yesterday's blog) took me to a great neighborhood pizza-and-beer joint called Pizano's at State and Chestnut Streets. The far wall is a painting, a la the Boulevard of Broken Dreams, featuring the likenesses of Sammy Davis Jr., Marilyn Monroe, Elvis, Frank Sinatra, the two brothers who own the place, Roy and Lou, and Jerry Seinfeld, who, strangely, is holding a cigarette. Roberta and I were enjoying our "refreshing summer beverage" (the actual name of their most popular drink) and we waved the bartender over. Why, we asked, is Jerry Seinfeld the focal point of a mural dedicated to dead Rat Packers? Look closer at Seinfeld, he said. Can you tell who it used to be? I squinted. No hints of anyone else. Based on context, though, I guessed Dean Martin. Wrong. After Frank Sinatra died in 1998, the bartender explained, a few regulars started a death pool. This, of course, made the brothers Roy and Lou nervous, since they were the only two people left among the living. Roy and Lou at once commissioned a painter to transform James Dean into Jerry Seinfeld, rationalizing that they both had a decent chance of outliving the comedian. As an added precaution, they kept the rebel's cigarette intact. ÷ ÷ ÷ The legendary Mike Royko was in the Tribune offices one day in 1991, when a young reporter rushed up to him. Do you know who's at the Billy Goat Tavern right now? she asked. President Bush. And he wants to meet you. He wants to know which part of the bar where you usually sit. (Royko, in a column about the incident, wrote: "The country is going to hell in a handbasket, and the president of the United States wants to know on what part of the bar I rest my elbows? Or forehead?") Royko, like many other Billy Goat regulars, didn't appreciate the throngs of yuppies and tourists who began showing up once John Belushi made the place famous in his Saturday Night Live "cheezbooger" skits. And President Bush, he reasoned, is "the greatest tourist of our time." One hundred fifty Billy Goat regulars and reporters from the Washington press corps stood, stark quiet, and watched the first President Bush eat a cheeseburger and a bag of potato chips. A cadre of Secret Service men watched the regulars. Mike Royko was not among them. "The excitement at Billy Goat's should be over by now," he reported the following day. "I hope Dan Quayle isn't in town." ÷ ÷ ÷ And the last story is from Sin in the Second City. Chicago's rank-and-file press corps spent more time at the Everleigh Club than in their offices. Minna Everleigh always recalled the morning a fire erupted in a warehouse near the Levee district. Flames spread, trapping several inside. An alarm shrieked through the streets. An editor at the Tribune called for reporters. No one responded. Sighing, he picked up the phone and dialed the Everleigh Club's phone number: Calumet 412. "There's a 4-11 fire over at Wabash near Eighteenth Street," he said. "Any Tribune men there?" "The house is overrun with 'em," a maid replied. "Wait a minute, I'll put one on." ÷ ÷ ÷ If anyone out there has a favorite Chicago story, I'd love to hear it! Shoot me an email at: [email protected]. ÷ ÷ ÷ Karen Abbott worked as a journalist on the staffs of Philadelphia magazine and Philadelphia Weekly, and has written for Salon.com and other publications. A native of Philadelphia, she now lives with her husband in Atlanta, where she's at work on her next book. Visit her online at

|

Guests

by Karen Abbott, July 16, 2007 2:57 PM

During the three years I spent researching Sin in the Second City, I spent most of my time wearing ratty jeans and a baseball hat, hunkered down in the dark corners of libraries, sifting through musty old archives. I became so immersed in the material that I would rarely break for lunch, and instead crouched in a bathroom stall and gnawed ferally on a cereal bar and rushed back to my seat so I didn't lose my train of thought. I became a bit of a recluse; most of the people I talked to happened to be dead (fortunately, one doesn't have to be alive in order to be interesting). Which is all to say that the hermit mindset is conducive to research, but promotion ? not so much... I flew into Chicago last Thursday, the day after a launch party at the Museum of Sex in New York. My friends, Fales and Roberta, picked me up at the airport and announced that we "have some work to do." I was pretty beat from the festivities ? all I wanted to do was curl up on a couch and nurse my champagne hangover and try to convince myself I did nothing too embarrassing and cling to the consoling thought that at least my mother wasn't there ? but instead I found myself at a bar in the Hotel Sax on Dearborn Street, far north of where the Everleigh sisters once reigned. Fales and Roberta both happen to work in public relations, and call themselves, respectively, "The Pimp" and "The Witch." Fales came armed with a copy of Sin, a review of the book in that day's New York Times (which she insisted I "laminate immediately") and a leather satchel for collecting business cards. "I'm telling you," she said, "it's all about connecting with people, engaging them and directing the conversation." Roberta and Fales conferred and decided to work opposite ends of the bar. Fales approached the bartender, ordered a wine flight, and gave me a shove. "Do you want to meet a famous author?" she asked. "She was in the Times today. Hugh Hefner is reading a copy of her book right now. She's going to be on Oprah." All of which, the Times review notwithstanding, was news to me. Roberta appeared, a guy in a three-piece suit by her side, whom she introduced as "Nelson." Nelson, she said, was going to help us spread the word. Fales was delighted to have a new recruit, especially one of the opposite sex, since he could go places we couldn't, like the men's rest room, and slip copies of my book under the stalls. By the end of the night, she had concocted a back story: Nelson (whom Fales nicknamed "Half Nelson") and I recently divorced but were still on amicable terms. We were hawking copies of my book in order to support our young son, Quarter Nelson. I don't think we sold any books, but Nelson did pick up the tab, which Roberta insisted counted for something. This guerilla pimping, as Fales called it, continued the next day. We hit this fabulous BYOB Mexican place called Wholly Frijoles out in Lincolnwood, which Fales picked precisely because there's always a long wait for tables, and patrons usually gather out in the parking lot and drink. By the time we were seated, Fales had invited every tipsy passerby to a grand ceremony in which Mayor Richard Daley would be presenting me with a key to the city. While I perused the menu, she handed a copy of my book to the waitress and repeated the word "prostituta" over and over again. I was still unconvinced any of this was working, but I didn't want to seem ungrateful. I had gotten in the habit of standing idly by while Fales delivered her pitches, each more outlandish than the last, and then piping in at the end to ask for business cards. On our next outing, we went to sign stock at a few suburban bookstores. As we left a Barnes & Noble, a car pulled up next to ours. The driver rolled down his window. Fales nudged me. "See?" she said, excited. "He knows it's you!" "Excuse me," the man said. "Do you know how to get to Drury Lane?" Undeterred, Fales suggested we stop by a crowded Noodle & Company for lunch. As the cashier rang up our order, Fales waved the (still unlaminated) New York Times review and launched into her spiel. When she stopped, I felt compelled to fill in the silence, and asked if he had a card. The kid blinked. "A card?" he asked. "What's that?" I looked at him more closely. A constellation of pimples spread across his chin. He couldn't have been older than seventeen. "Do you think I'm someone important?" The kid was laughing now. "I work at Noodles & Company." The kid clearly felt sorry for me, and gave us a wad of coupons toward our next meal at Noodles & Company. Which, I suppose, counts for something. ÷ ÷ ÷ Karen Abbott worked as a journalist on the staffs of Philadelphia magazine and Philadelphia Weekly, and has written for Salon.com and other publications. A native of Philadelphia, she now lives with her husband in Atlanta, where she's at work on her next book. Visit her online at

|