Guests

by Tom Spanbauer, April 11, 2014 10:46 AM

Tell us about the places you have written. The actual place where you set up your writing desk. Were there windows you looked out of? What did you see?  Faraway Places was written at 211 East Fifth Street, Apt. 1A, in Manhattan. My apartment was a studio about nine feet wide and not a lot longer. I got the apartment for free and $400 a month for being the super of three buildings on East Fifth. There were two long, narrow windows facing East Fifth Street, but I always had the rust-colored Levolors closed. My first computer was on a small table that butted up against a larger dinner table. From where I sat, I could reach out and touch the kitchen sink. Behind me was one of the only two places in the studio where two people could stand. Right behind me was the bathroom door. You had to move the chair to get into the bathroom. In the loft bed above the bathroom I had a black and white TV with a coat hanger for an antenna. I could only get PBS and for some reason only old Star Trek episodes. There was a window in the loft bed area that looked onto a black-tarred air shaft. Faraway Places was written at 211 East Fifth Street, Apt. 1A, in Manhattan. My apartment was a studio about nine feet wide and not a lot longer. I got the apartment for free and $400 a month for being the super of three buildings on East Fifth. There were two long, narrow windows facing East Fifth Street, but I always had the rust-colored Levolors closed. My first computer was on a small table that butted up against a larger dinner table. From where I sat, I could reach out and touch the kitchen sink. Behind me was one of the only two places in the studio where two people could stand. Right behind me was the bathroom door. You had to move the chair to get into the bathroom. In the loft bed above the bathroom I had a black and white TV with a coat hanger for an antenna. I could only get PBS and for some reason only old Star Trek episodes. There was a window in the loft bed area that looked onto a black-tarred air shaft.

The Man Who Fell in Love with the Moon was also written at 211 East Fifth Street, Apt. 1A, but was completed in Portland, Oregon, on 4005 SE Milwaukie. The building is a store front and I set up my computer in an abandoned hallway. I don't remember any windows, but the door was opaque glass. One night while writing, a Reed College student, a young woman high on acid, ran into my Chevy Citation parked in front of the house. My car was totaled. In the City of Shy Hunters was written everywhere. I started the book when I lived at 21 SW Mitchell, Portland, Oregon. My partner and I bought a derelict house and built it up from the floorboards. The first room that was finished enough for me to write in was my upstairs bedroom. A low, slanted ceiling, cold in the winter and unbearably hot in the summer, and I-5 roaring past about one hundred feet away. The window looked out to a huge Lombardy poplar that died as soon as we bought the place. Finally we finished the lean-to of the house and I set up writing in there. I bought a new window and a new glass door. After all the years of writing, I finally had my own writing room. There was room for a couch where I could take a nap, my computer and my desk, a book shelf, and a small table. When I looked out my new window, I could see into my neighbor's bathroom. It was a rented house, so I got to see a lot of different people taking a crap. In 1993, I was given the honor of being the Writer in Residence in Barcelona, Spain. My apartment was a little house on top of a high rise on a street called Alfons X11. On the sidewalk, if you wanted to buzz me, you had to push subratico. A wonderful, scary, tiny elevator. And six floors of winding staircase. Outside my window I could see a big chunk of Barcelona. I had my own private terrace where I hung my washing out to dry. There was a big double bed and a big closet. But where did I put my computer? In a closet. I guess writing is such an internal thing, I can't be distracted by the real world. I finished Shy Hunters in a back shed at 21 SW Mitchell in Portland. Again, I set up my computer in a corner closet. I got AIDS about then. One day I remember making it out of bed, getting my clothes on, walking slowly out to the shed, sitting down at my computer, starting it up, and opening up a file. I wrote the sentence: On October 3, 1986, one year and a day after Rock Hudson died and four months after Gay Pride, I dialed 911 for Rose. And that was it. I had used up all my energy for the day. Now Is The Hour and I Loved You More were written where I now live on SE Morrison. My computer is in an armoire in the corner of the living room whose doors I close when I finish writing. I didn't mention that over the years, in each one of these tiny, crowded, dark corner closets where I put my computer, the computer itself and the area around it always became an altar of shiny found objects, all of which I threw away when I finished the book I was working

|

Guests

by Tom Spanbauer, April 10, 2014 10:19 AM

In my novel, In the City of Shy Hunters, there were so many dead friends to write about. There's a line in Shy Hunters: "It's the responsibility of the survivor to tell the story." As I was writing the book, I felt the wisdom of that line very keenly. And since I was the one responsible, I had to get the story right. In order to get the story right, I had to go back to the Manhattan of the '80s and tell everything I knew that was true about those days, everything that was true about that place. I really became obsessed by it. For many people, the story of In the City of Shy Hunters is just too harsh and too real. There is so much death and it doesn't let up. But that's the way it was for me. Everyone was dying and I knew I was sick and nowhere could I find redemption. In many of my books, I go to nature to soften the blows of the hard story I'm telling. But in Manhattan, there was no nature. Even Central Park was designer nature. So there was no respite. The widespread affliction, the calamity, wasn't just death. The epidemic was also the fear of death. Nowhere to run. Nowhere to hide. That's what a plague is. In Now Is the Hour, the character of George Sereno was based on a Native American man I baled hay with one summer. At the end of Now Is the Hour, the character of George and the narrator become lovers and drive off into the sunset. I was a little concerned about the happy ending — in the sense that perhaps I was creating a "feel good" book. But I was also concerned because the "real" man I'd baled hay with had killed himself. The concern was, Do I have the right to retell this man's story with a different ending? I remember the writing moment when I decided not to end the life of my invented character. I was at a point in the story where I could've had George, out of fear and desperation, choose to kill himself, the way the man I knew had. But I chose a happier ending. I guess I somehow hoped that by writing a happier ending, perhaps in some way I could dispel some of the suffering of the real man. I know that is me playing God. But I am God in my novels, so I decided to give the invented man the hope of a future the real man didn't have.  In I Loved You More, the character of Hank is based on a good friend of mine. My friend died in 2008 and we hadn't spoken in seven years. In many ways I Loved You More is an open love letter to him. And I really loved writing this love letter. I loved re-creating my friend as a character. Of course, almost immediately in the writing, the character I created wasn't my friend at all. He was my invention of my friend. But then I really came to love my invented character. Maybe even more than I loved my friend, but I don't think so. There were so many ways this love letter was wonderful. Mostly, I had the opportunity to remember — to actually go back to places and events and make myself be present in them and go through them again. There's something so strange about fiction, telling the lie. The lie actually brought me back to times and events and places I had totally forgotten. Ultimately, by telling this story, I came to understand so much that I would never have understood about my friend, about us, had I not written the story. And on my part, so much was forgiven. When you forgive, you lay your burden down. You don't have to carry it anymore. And by writing this love letter, somehow there is also the hope that my dead friend can lay down his burden In I Loved You More, the character of Hank is based on a good friend of mine. My friend died in 2008 and we hadn't spoken in seven years. In many ways I Loved You More is an open love letter to him. And I really loved writing this love letter. I loved re-creating my friend as a character. Of course, almost immediately in the writing, the character I created wasn't my friend at all. He was my invention of my friend. But then I really came to love my invented character. Maybe even more than I loved my friend, but I don't think so. There were so many ways this love letter was wonderful. Mostly, I had the opportunity to remember — to actually go back to places and events and make myself be present in them and go through them again. There's something so strange about fiction, telling the lie. The lie actually brought me back to times and events and places I had totally forgotten. Ultimately, by telling this story, I came to understand so much that I would never have understood about my friend, about us, had I not written the story. And on my part, so much was forgiven. When you forgive, you lay your burden down. You don't have to carry it anymore. And by writing this love letter, somehow there is also the hope that my dead friend can lay down his burden

|

Guests

by Tom Spanbauer, April 9, 2014 10:00 AM

What for you is the relationship between writing and death? Not just literal death but dying emotionally, psychologically, spiritually. Dying to one's own ego, dying to what's allowed and what's forbidden. Writing about the dead and bringing them back to life through writing? I'll try to answer this part of the question: What is it like for me to die to what's allowed and what's forbidden? Part of the fictive invented I is that you get to be braver, bigger, stronger than you really are. There are risks you can take sitting at home at your computer that out there in the real world are much more difficult to do. But that's what fiction is for. In real life, you may wish you would have done or said something at a certain time. With fiction, you don't have to wish. You can do it. But just because it's fiction doesn't mean it's not a difficult task. To face up to your demons takes a lot of chutzpah wherever you are. Most of what we fear is internal. Most of what we fear is the way we've internalized our parents, our religion, the bullies who hated us. Heidigger defines thinking as: the silent conversation we are having with ourselves. So what we fear actually are our own ingrained thought patterns — the way we have been talking to ourselves our entire lives. So even to call out the name of our devils in our little writing rooms with our cups of tea and the space heater by our feet, requires great courage. (Remember yesterday's Zen saying: within us all there is a great battle waging?) I'll try to answer this part of the question: What is it like for me to die to what's allowed and what's forbidden? Part of the fictive invented I is that you get to be braver, bigger, stronger than you really are. There are risks you can take sitting at home at your computer that out there in the real world are much more difficult to do. But that's what fiction is for. In real life, you may wish you would have done or said something at a certain time. With fiction, you don't have to wish. You can do it. But just because it's fiction doesn't mean it's not a difficult task. To face up to your demons takes a lot of chutzpah wherever you are. Most of what we fear is internal. Most of what we fear is the way we've internalized our parents, our religion, the bullies who hated us. Heidigger defines thinking as: the silent conversation we are having with ourselves. So what we fear actually are our own ingrained thought patterns — the way we have been talking to ourselves our entire lives. So even to call out the name of our devils in our little writing rooms with our cups of tea and the space heater by our feet, requires great courage. (Remember yesterday's Zen saying: within us all there is a great battle waging?)

It takes balls to make a safe place for yourself where you can tell what is true for you. What is true for you is usually not allowed and is forbidden. Fiction is the lie that tells the truth truer. In Faraway Places, my narrator confronts the character of his father in a way that I only later in real life was able to do with my own father. If I would never have done it in fiction, I doubt I'd have done it in real life.  In The Man Who Fell in Love with the Moon, I got to be something little Catholic Tommy never had the chance to be: a whore. A man who takes money for his sex. It was very liberating. I also got to take on the Dogmatic Man and His Little Black Book; that is, I got to take on established religion and show what a bunch of horse shit it really is. And there's something else quite daring about Moon, and I'm quite proud of it. I got to write about the Old West the way you'll never see in John Wayne movies. One reviewer called Moon "postmodern," meaning I blended in current trends or styles into a classical history. Postmodern my ass. Homosexuality has been around as long as there have been human beings. In The Man Who Fell in Love with the Moon, I got to be something little Catholic Tommy never had the chance to be: a whore. A man who takes money for his sex. It was very liberating. I also got to take on the Dogmatic Man and His Little Black Book; that is, I got to take on established religion and show what a bunch of horse shit it really is. And there's something else quite daring about Moon, and I'm quite proud of it. I got to write about the Old West the way you'll never see in John Wayne movies. One reviewer called Moon "postmodern," meaning I blended in current trends or styles into a classical history. Postmodern my ass. Homosexuality has been around as long as there have been human beings.

In In the City of Shy Hunters, I killed a cop and fucked the archbishop. Now Is the Hour, I got to talk about racism. Me, little old white me, talking about racism. Not in LA, not in New York City, not in Mississippi. Racism in a rural Idaho town. In I Loved You More, I got to write a love story that only gods could bring about. A gay man and a straight man loving each other. A straight woman and a gay man loving each other. And then the three of them, the gay man, the straight man, the straight woman, a love triangle. Each one of them is intelligent, educated, an artist. All of them are caught up in a tragic mess of ambiguities only the very particularities of the three of them could bring about. Love, death, religion, racism, gender, sex. Little Tommy Spanbauer could never have written about these things. In order to write about these big life things, I had to step up. Had to die to what's allowed and what's

|

Guests

by Tom Spanbauer, April 8, 2014 10:00 AM

You write about things that are deep and painful. Do you emotionally relive the painful feelings and experiences? Does the process of writing your novels bring pain or relieve it?  I write about things that make us human. There is a great Zen saying that goes: when you meet someone, look them closely in the eyes, for inside those eyes a great battle is waging. Really all of us human beings are essentially in the same place. We are on a battlefield. Each battlefield may be different, but in the end, we're all facing some very human things: aging, loss, sickness, and death. I write about things that make us human. There is a great Zen saying that goes: when you meet someone, look them closely in the eyes, for inside those eyes a great battle is waging. Really all of us human beings are essentially in the same place. We are on a battlefield. Each battlefield may be different, but in the end, we're all facing some very human things: aging, loss, sickness, and death.

Someone asked me once if I have a writing muse. I answered that I go to where it hurts inside me. Or I go to where I feel most afraid. Where we find resistance inside us is where our muse lives. While I am writing I feel the pain, or I purposely go to where the pain is and conjure it up. The trick for me is that I'm writing in first person. I have invented an "I." And this invented "I" as soon as I write it down is not "I" the writer but "I" the narrator. The narrator almost immediately begins to lie. I think it's practically impossible to make the invented "I" not lie. The invented "I" is fictive and cannot be the same as the "I" who is writing. The invention is by its very nature different than the inventor. So as soon as this new "I" starts to speak, it has an existence of its own. I don't think there is a way around it. After a couple of pages, the "I" that I have created may look like me, and have the same hang-ups as me, and may have the same sense of humor, but there's something different about this new "I." And the difference is: this new "I" is not me, but an invention of me. In my opinion, this invented "I" is quite different from a third-person invented "he" or "she." Speaking as the "I" keeps the narrator actively in the story. The story is happening to the "I." With the third-person narrator, the story is happening to this or that person over there ("him" and "her"). Third person places the narrator, as an awareness, perhaps omniscient or "close-in," but always outside the events that are happening on the page. This distance varies with different styles, but always that distance is there. (And maybe that's what you want.) And by the way, that distance between the writer and the invented third person is often that written sound of writing that I talked about yesterday. The invented "I" allows the writer to still be in the story, and not outside the story explaining the story, the way the invented "he" or "she" is. And something mysterious. Since the invented "I" is not the "I" of the writer, the invented "I" gets to feel the tough emotions, while the "I" of the writer watches in an extremely close, if not totally absorbed, personal proximity. The "I" you have created can feel the pain instead of you because you have invented this "I" to do just that: feel it for you on the page. Or at least, the invented "I" can allow the writer to be the character in the invention to feel the pain. In a way it's like therapy. You get to a point where you can talk about yourself experiencing pain as if you were someone else who experienced it. And to answer the second part of the question: writing fiction like this, dangerous writing, is a scary line to walk. Sometimes reliving the pain is just that. Whether you do it or your first-person narrator does it. Sometimes you can transcend the pain and turn it into understanding. But understanding like that doesn't happen often, and when it does, it is a great

|

Guests

by Tom Spanbauer, April 7, 2014 10:00 AM

If you could dispense with a single point of advice/wisdom to a new but promising writer, what would it be? And why?  Your best friend is in town and you haven't seen him or her in years. You have something very profound that has happened to you that your friend does not know about yet. You go to a bar and after two margaritas you begin to tell her/him this very important thing that has happened to you. Remember, you are intimate with this person. You don't have to keep up any appearances. Because you trust your friend, you can let it rip. Nothing is taboo. This profound thing is something that you must share. In fact, the actual sharing of it with your friend is a huge part of its importance. Your best friend is in town and you haven't seen him or her in years. You have something very profound that has happened to you that your friend does not know about yet. You go to a bar and after two margaritas you begin to tell her/him this very important thing that has happened to you. Remember, you are intimate with this person. You don't have to keep up any appearances. Because you trust your friend, you can let it rip. Nothing is taboo. This profound thing is something that you must share. In fact, the actual sharing of it with your friend is a huge part of its importance.

You're going to treat this experience with your friend as if you were talking to your friend but actually you are writing. The trick is to write like you talk. Often the trouble with writing is that it sounds written, not spoken. So many of us have years and years of creative writing jammed into our heads, and as soon as we sit down to write, the sound that is creative writing starts coming out. It is an insidious sound. My teacher called it writing to the page. And you can hear it immediately. For example, any movie that has a scene where a character reads a piece of writing, the way that writing almost always sounds is how we think writing should sound, and that's what I mean when I say it sounds written. Oftentimes, just reading your writing aloud can help you hear if it sounds like you, or if it sounds like you writing. Don't be afraid to break syntax rules. Use run-on sentences and sentence fragments. Really try anything to make it sound fresh and alive. Repetition of words. Choruses. Bad grammar. Cursing is allowed. One of the sure signs that you have succeeded in not sounding like writing is if you, by surprise, make yourself

|

Guests

by Tom Spanbauer, December 11, 2013 5:14 PM

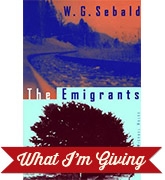

In this special series, we asked writers we admire to share a book they're giving to their friends and family this holiday season. Check back daily to see the books your favorite authors are gifting. In this special series, we asked writers we admire to share a book they're giving to their friends and family this holiday season. Check back daily to see the books your favorite authors are gifting.÷ ÷ ÷ I'm giving this book to my partner, Michael Sage Ricci, because Sage and I, as well as being partners and lovers, also teach Dangerous Writing together. Sage and I are constantly talking about books and writing, and in particular styles of writing. Sebald's style is like no one else's, and while I'm in love with his books, especially The Emigrants, I am confounded as to his style, and mystified by his style, and while I have some ideas as to how Sebald does what he does, I won't really understand what I want to understand until I talk to Sage about it. I read this book because my therapist, Grey Wolfe, had been raving about Sebald and she'd just recently finished The Rings of Saturn, so I bought The Rings of Saturn, loved it, and wanted to read another book by Sebald. The Emigrants is a long meditation, or guidebook, through the lives of four Germans in exile. These people are strangers, outcasts, people who do not belong. This not-belongingness is geographical, but this strange otherness that Sebald gives witness to is so much more. Each of these four people have been wounded so deeply that they never recover from the wound. The Holocaust was a blow to their very deepest human place. A blow of deep unending grief. And with grief comes the isolation of grief, and exile. Home is a place that no longer can exist because that place in us that gives us succor has been ruined. At every hour of the day and night, the Wadi Halfa was lit by flickering, glaringly bright neon light that permitted not the slightest shadow. When I think back to our meetings in Trafford Park, it is invariably in that unremitting light that I see Ferber, always sitting in the same place in front of a fresco painted by an unknown hand that showed a caravan moving forward from the remotest depths of the picture, across a wavy ridge of dunes, straight toward the beholder.  Funny story: I read The Emigrants while I was on vacation with Sage in Maui. Our Hawaiian hosts had a beautiful house and garden. In the garden, among other beautiful tropical plants, was a peyote plant, which quite miraculously that morning had bloomed. I want you to know that a peyote plant blooming is a very rare thing. And the bloom lasts for only several hours. Well, as destiny would have it, the day I was left alone at the house was the day the peyote plant bloomed. There on the plant was a tiny purple bloom, almost like a daisy. I was reading The Emigrants on the lanai and it was a beautiful day. Our hosts had often spoken of the spirits in the valley where we were staying. The magic of the valley and the magic of the book were quite overwhelming. Funny story: I read The Emigrants while I was on vacation with Sage in Maui. Our Hawaiian hosts had a beautiful house and garden. In the garden, among other beautiful tropical plants, was a peyote plant, which quite miraculously that morning had bloomed. I want you to know that a peyote plant blooming is a very rare thing. And the bloom lasts for only several hours. Well, as destiny would have it, the day I was left alone at the house was the day the peyote plant bloomed. There on the plant was a tiny purple bloom, almost like a daisy. I was reading The Emigrants on the lanai and it was a beautiful day. Our hosts had often spoken of the spirits in the valley where we were staying. The magic of the valley and the magic of the book were quite overwhelming.

In the afternoon I got up and went for a stroll in the garden. When I spied the peyote plant, I was quite surprised to see that the bloom had already withered and all that was left of the bloom was a nub. For some reason, I knelt down and kissed the nub of peyote bloom, then walked back to the house to continue reading. At sunset, the fog started to roll in and I began feeling very strange. Reading Sebald can do that to you, but this was formidable. I was on the last page of The Emigrants just as the sun was going down. When I came to the final sentence, I was transported by the incredibly unsettling last image in the book of the three young Jewish women in the concentration camp sitting behind the loom and looking up at the photographer. "...the daughters of the night, with spindle, scissors and thread." I set the book down and took a deep breath. The otherness of my body. As if I were exiled. The peyote kiss. It took me a while to realize I was tripping my ass off

|