"I admit to being moved by a peanut kernel" and "eventually I made a pilgrimage to a coat," are odd-sounding sentences on their own. For me, they are points of interest on the far edges of a map that began with an un-assuming visit to Philadelphia's

Mütter Museum in 2006.

Among the numerous pathological specimens housed in the museum, the Chevalier Jackson Foreign Body collection stopped me in my tracks; I guess you could say it literally fascinated me (fascinate having origins in arrest and paralysis and the casting of spells). I wasn't alone in this — the beguiling drawers filled with thousands of items that people had swallowed or inhaled, items neatly framed, stowed, organized by type, and meticulously cataloged by the doctor who extracted them, is for many visitors to the museum among its most memorable displays; it may even be the museum's most popular attraction. The collection no doubt exerts a singular charge for each person — I'm convinced that viewing the foreign body collection is a visceral experience, sensuous at its core, and yet it is made manifest by presumably inanimate objects. Some people even opt to return to peruse it again and again, and eventually make art from it or write to it.

My own initial interest in Chevalier Jackson's collection of "foreign bodies" was an aesthetic one. Simply, I felt there was poetry happening in these drawers, in much the same way a poet like Talvikki Ansel (My Shining Archipelago) finds poetry inside of the periodic table of elements. Jackson's collection initially interested me as a cosmology of things — what a strange universe the maker of the collection had constructed, in which types and orders and clusters, combinations, constellations, and cross-references were built — but built out of what? Objects that people had swallowed or inhaled.

There was something ineffable about each object, and jewel-like, both because and in spite of the fact that each bespoke the body from which it hailed, a life nearly cut off, most of the time saved because of Jackson, an uncanny lodgment that re-made both the thing and the person who had ingested it.

I thought maybe an experimental essay could do justice to the objects' strange aura — from buttons, nails, and screws, to jackstones and toy binoculars, pencil nibs, coins, a padlock, more than one crucifix, and a Perfect Attendance pin. I'm a reader, and I saw from the exhibit that Jackson had also left a great deal of writing in his wake, including an autobiography that was a best seller in 1938 (written when the physician was 73 years old). Reading the autobiography was difficult. It was finely written — that wasn't the problem — but the first fifty pages were rife with tales of a barely survivable traumatic childhood. There was cause for an essay-poem as a response to the collection — that had been clear — but Jackson's autobiography showed me that there was an entire book waiting to be written from inside his cabinet of curiosities, that the collection was haunted by his own complex psychology and by the lives of his patients running like silent, invisible movies, the scenarios of accident and desire, the vectors of volition and struggle, of poverty and hunger (why do you think people put things in their mouths?) that each foreign body told. Nonfiction was called for because the stories buried in Jackson's papers and in the thousands of case studies in places like the National Library of Medicine collection were often stranger than anything I could possibly make up.

I didn't aim to offer a corrective to the foreign body display — as though it could be "completed" by the restoration of its missing parts, because the beauty of the collection is its inexhaustible suggestiveness, what it hints at, provokes, draws forth, points to, how it invites the imagination to wander. I was, though, excited by the social histories lurking inside each object and was moved to have stumbled upon a life as magnificent as Chevalier Jackson's.

Trauma plays about the edges of the foreign body cabinet — Jackson's, his patients', and my own (a stomach-pumping episode in my early childhood was the result of the otherwise deeply pleasurable imbibing of bubble bath). My father had a habit of warning my brothers and me that much of the object world was swallowable, and therefore dangerous. Is this what incited my interest in the Mütter Museum's collection of foreign bodies, objects caught, extracted, and stowed?

Trauma plays about the edges of the foreign body cabinet — Jackson's, his patients', and my own (a stomach-pumping episode in my early childhood was the result of the otherwise deeply pleasurable imbibing of bubble bath). My father had a habit of warning my brothers and me that much of the object world was swallowable, and therefore dangerous. Is this what incited my interest in the Mütter Museum's collection of foreign bodies, objects caught, extracted, and stowed?

I think it was love, not aversion, that drew me closer, a love of miniatures, and paper dioramas — a particularly intricate miniature village that my mother unfolded each Thanksgiving, or the claymation theaterspaces that clicked into place and opened like a fan into awe when the View-master was held to the light. Though the foreign body collection's amplitude is part of what makes it astonishing, there's also a way in which you have to shrink in order to "enter" it. I'm a lover of secondhand things and a frequenter of yard sales; finding objects that lives have passed through is always more interesting than buying something new. Foreign bodies reversed that process: they had done the passing through; they were peculiarly secondhand.

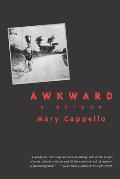

In a recent interview with the Mütter Museum's director, Robert Hicks, the magnificent filmmakers the Brothers Quay discussed their film-in-progress (premiering this fall) based on objects in the museum. I've loved the Quay Brothers' films forever, and can't wait to see what they will make from these materials. Timothy Quay spoke of the "terrifying beauty" of particular objects in the museum — amputation tools, for example — and their current "benignity" bathed in a beauteous light. I have this same experience of terrible beauty when confronted with Jackson's foreign bodies — those ingredients of the sublime. And I suppose an ethical dimension enters in when one figure in that dyad displaces or competes with another — terror/beauty. Then I find another order of interest is called upon, and I can't retreat. A Perfect Attendance Pin first attracts me for its whimsy, until I learn the details of the case, whose poignant horror calls upon a different order of awe and need to investigate. A collection of 32 objects all swallowed by the same nine-month-old baby, carefully assembled into a hieroglyphic collage by Jackson, enmeshes me in wonder. Until I find in the case study major details that Jackson never told: that this boy was forced to swallow these things by a babysitter. Now a foreign body asks me to find a language for atrocity. To really take it in. It takes me into realms far from palatable — and I don't mean that in a humorous way. One kind of interest yields another order of interest if we let it, and demands that we broach another capacity. I will call it "understanding" for lack of a better word. I guess this is my way of saying that working with the foreign body exhibit took me into areas that I did not really want to think about — and that disquietude in itself interested me (I had, after all, written another book on discomfiture called Awkward). I know, for example, that what seems beyond understanding implicates us most of all.

All that a button asks, in the foreign body exhibit, is that one follow one's interest in it, and — if one does — that one arrive at the multiform perils and pleasures the collection represents and incites. Because what's more marvelous? The life of Chevalier Quixote Jackson ("Chevie" to his family); the instruments he designed, the awesomeness of his use of them; his depositing them into a collection; the incredible dimensions of the fact of ingestion, or the incredible dimensions of the fact of extraction? The art made from a view through a peephole the diameter of a straw that gives way to pinkly-graded inner landscapes never before glimpsed? Following one's interest, one discovers that there is no such thing as a foreign body but various orders of such: phantom foreign bodies; multiple foreign bodies; voluntary swallows of non-nutritive things, and forced. There's the allure of errant foreign bodies and the special charge of message-laden foreign bodies. And finally, there's the art the doctors who remove them make from them in order to tame what they cannot understand: that some things, unlike human bodies, are imperishable and insoluble. That foreign bodies are inassimilable by human bodies (and human psyches), and as such, have much to say about all the "stuff" of life that can't be taken in.