Yesterday I did an interview with a Danish journalist. He's doing a story on taqwacore, which is loosely and badly translated as "Islamic punk rock." He was a real cool guy and I had a good time talking to him.

I've spoken with Danish journalists before, and conversation logically ends up at the Muhammad cartoon controversy from a few years back. The uproar over the insulting images of the Prophet caused a UK publisher to heavily censor my novel, The Taqwacores.

Western media tends to divide Muslims into two very simple categories: the secular, liberal, West-friendly Muslim, and the angry, violently intolerant Muslim, always with a big bushy beard and invisible wife. When you only have these options, there's not much room to move around in ? and little chance of understanding taqwacore kids, who might drink beer, have sex, doubt the existence of God and divinity of the Qur'an, but then sing a song called "Shari'a Law in the USA." The previous Danish writer to interview me was surprised when I went off against the cartoons.

"But your book is like that," he argued.

He just didn't get it, and I can't say that I really blame him. It's a hard distinction to make, since he could actually argue that The Taqwacores is a lot worse than the Danish cartoons. Besides, if you look at the cover of the current edition, the praying man's head wears a halo of flames ? which commonly graced the head of Muhammad in classical Islamic art. But the guy has no face, so I guess it's okay.

Blasphemies aside, I do call myself a Muslim, and from what I can tell, that's also apparent in the way that I treat these materials ? the Prophet, the Qur'an, and God ? in the book. I always saw the blasphemies in the novel as truly Islamic; the Prophet smashed idols, but what if the Prophet himself becomes an idol? Then you smash him, right? And see what's still there. The novel was like a teenager throwing a tantrum at his parents. You can say all kinds of things about your loved ones, but it's different when someone insults them from the outside.

That first journalist found it completely bizarre that I would take offense at racist cartoons, but still defend the cartoonist's right to exist ? that I could somehow respond as both a Muslim and a rational human being in the modern world. It forced him to create a third category. The journalist from yesterday was a bit surprised at my take on things ? he might have been expecting me to just rip on Islam ? but he seemed to get it, so much respect to him.

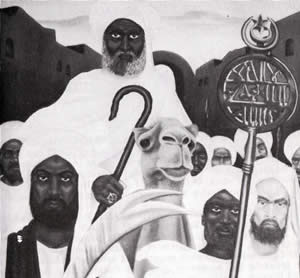

I do appreciate the fact that Muslims typically avoid images of Muhammad, but I also have images of him, made by Muslims. Here are depictions of the Prophet by the Nubian Islamic Hebrews, a sect that originated in New York in the 1970s. I like the one of the Prophet on his camel, with Ali, Bilal, and Abu Bakr in front of him. You can see the intersection of black supremacy and Shi'a sympathies in the way that the artist depicted Abu Bakr as pale compared to everyone else.

I want to build on this censorship thing. I've actually been sued over my work, but the censorship hurt worse. After the burning of embassies, cuts of outright blasphemies should have been expected; but the publisher also wanted to delete any obscene word that appeared in the same sentence as Allah, the Qur'an, or the Prophet, regardless of whether it was in direct reference. Even a character being described as "anal" in his adherence to the Sunna had to go, since the editor thought that this associated the Prophet with anal sex.

Besides words, they went for ideas. Discussion of Ayesha's age at the time of her marriage to the Prophet was not allowed, regardless of the tone. With the help of an anonymous "consultant," my editor suggested the deletion of "problematic" sections dealing with facts of history, such as the Qur'an being collected and put into book form after the Prophet's death, or the story of the Necklace, in which Ayesha speaks to the Prophet in a defiant manner ? though these events are accepted by the Muslim community, and included in pious literature. Islam itself has been tagged as offensive to Muslims.

Because the uncensored US edition was also available in the UK, and each instance of censorship would be noted with an asterisk, I agreed to the cuts for their theatrical value; the whole book would become a performance, censorship as spectacle. The mutilated text served to demonstrate how ridiculous our discourse on religion has become ? that non-Muslim editors are telling a Muslim author how he can properly relate to his religion, and how Muslims will interpret his work.

The novel's burqa-wearing feminist character, Rabeya, self-publishes a zine called Ayesha's Hymen. My UK publisher insisted that its title be cut. If these changes were motivated by a fear of violence from offended Muslims, then the publisher has supported an image of violence as a Muslim's natural response, while also justifying the threat of violence as a means to govern speech. The bookseller has joined the book burners, leaving Rabeya as voiceless as she would be under the Taliban.

If the publisher's intention was to show respect for Islam, it was only a certain kind of Islam ? the monolithic Islam of uncompromised orthodoxy, the Muslim community as defined by its most conservative members, presuming all Muslims to believe and practice in one uniform fashion. This is an Islam that does not exist. The publisher was okay with my Muslim characters listening to the Sex Pistols, drinking beer, and having sex ? in short, conforming to secular Western culture ? as long as they never questioned the truth claims of their faith. It took a religious novel and stripped away the religion. Instead of engaging Islam with any honesty or imagination, daring to express doubts and unpopular beliefs, these characters were reduced to the children of immigrants who broke some rules on their way to assimilation: Muslim kids with bad haircuts and bad music who couldn't deal with their religion in any meaningful way.

The censorship of The Taqwacores in the UK expressed the publisher's view that my own experience of Islam is not legitimate, and that Islam is most accurately represented by so-called fundamentalists. In the name of tolerance and respect for cultural differences, the publisher denied that Islam itself could be diverse.

One reviewer wrote that this novel asked, "How do you define a 'true' Muslim? On what grounds? And does anyone have the right to judge?" The answer is yes, someone has claimed the right: the non-Muslim editor reading a manuscript with black marker in hand, running thick lines over my Islam.

After all of this, they had the sack to declare, "The Taqwacores is to literature what the Sex Pistols were to music."

The book has since been re-issued by Soft Skull Press, without any censorship, so thank Allah for them. And the Taqwacores movie is currently in post-production, thank Allah for the director, Eyad Zahra, and a brilliant, courageous cast and crew. This wasn't an easy story to tell; but when it's done, I think we'll be proud of the choices we made. As artists, that's all we're entitled to.