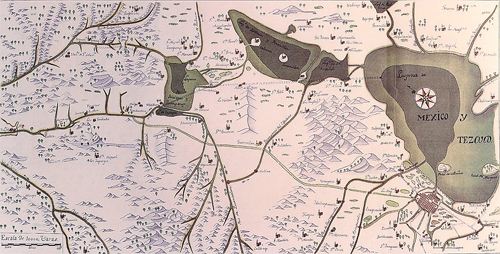

Mexico City sits in a basin ringed by mountains. Snowfall and rainwater pour down the slopes; the mountains prevent it from escaping; the basin becomes a marsh. Centuries ago, the area's first inhabitants dredged the muck, turning five small bodies of water into a single 80-mile lake shaped like a backwards

S. On the southern curve of the

S was a group of low, swampy islands. With considerable ingenuity, the Triple Alliance (Aztec empire) turned these islands into a city of canals — much like Venice, except that the city of Tenochtitlan was twice as big as Venice.

In its watery setting, Tenochtitlan dazzled the Spaniards who first saw it. Great causeways led across the lake to a city bigger than any in Spain, crowded with grand markets and opulent temples. An army of cleaners swept the streets — something the Spaniards had never seen. Another army of engineers vigilantly maintained the baffles, dams, and channels that kept spring floods from returning the city to its original state as a marsh. These latter efforts were invisible to Hernán Cortés and his troops. When they conquered Tenochtitlan in 1521, they unknowingly destroyed its water-control systems and killed off the engineers who ran them.

Click to view larger image.

As a group, Cortés and his successors had little experience with complex hydrodynamic systems. The Spaniards tried to rebuild the native water system when they transformed Indian Tenochtitlan into Spanish Mexico City, but didn't know enough to do the job correctly. The city decayed slowly, then faster. Not until 1555 did the first bad flood occur. Then, they happened more quickly: 1580, 1604, 1607. Each was worse than its predecessor.

Desagüe

Like every writer, I remove many passages from my work that I wish could remain — not so much for the elegance of the phrasing as the interest of the subject. Enthralling but irrelevant, I grumpily tell myself. Out it goes.

Sometimes I look for a place to wedge it back in. I copy the cut paragraphs, and then scroll through the manuscript, hunting for a spot to hit "paste." I try half a dozen locations, hoping to talk myself into believing that I've found a place for this thought, this idea.

For 1493, I spent weeks reading about Mexico City's drainage system. I collected a small library of maps and books. I managed to get to some of its most important outlets. But I never managed to fit the material into the book. Still, I remained fascinated.

The reason was that in 1607, the imperial viceroy, Luis de Velasco, proposed a technical fix to the water problem: the desagüe (plughole or outlet). The desagüe was an eight-mile-long channel that would drain water from Mexico City north into the Tula River, which would carry it into the Gulf of Mexico. The first four miles were to be a canal — easy to build, if costly. The second four miles would tunnel through the surrounding mountains, a different story. At its deepest point the desagüe would tunnel 149 feet below ground. No Spaniard had ever built anything like it. No European had — it was the biggest construction project by Europeans since the Roman Empire.

The tunnel, constructed at huge cost, cut mainly through soft soil and loose stone. The chief engineer, like most Europeans at the time, was a follower of Aristotle. Aristotle believed that the world was composed of four elements: earth, air, fire, and water. The four elements were in a hierarchy, higher members ruling lower. Because water was higher than earth, the engineers believed, the soft soil walls could not collapse and block its passage. Unsurprisingly, canal and tunnel repeatedly caved in and had to be rebuilt.

Few people like to spend time thinking about infrastructure, let alone pay taxes for it. After a taxpayers' revolt in 1623, desagüe maintenance stopped. Six years later Mexico City woke up to find as much as six feet of water on the streets. The lake washed over the causeways, blocking food shipments from the mainland. Foundations undermined, mansions and monasteries collapsed by the score. According to the archbishop, only 400 Spanish families stayed in the city, clustered on upper floors, futilely trying to pump away the rising lake. The figure, though surely too small, gives some idea how lonely the remaining inhabitants felt as they paddled their canoes through the ruined streets. Mexico City remained underwater almost continuously until 1634. Still nobody wanted to pay for a proper tunnel.

Mexico City (lower right) in 1774; north on left side of map

It was a paradox. The desagüe functioned in the summer, draining the city. Slowly the lakes got smaller; Mexico City was no longer an island; the canals that had long been one of its greatest features shriveled and disappeared. But the desagüe didn't work well enough to prevent spring floods. The city was inundated in 1645, 1674, 1691, 1707, 1714, 1724, 1747 and 1763. Flooding continued until 1900 when at last the dictator Porfirio Díaz built a proper drainage tunnel. Only then did the citizenry discover that the desagüe had efficiently removed the city's water supply.

European Engineering

The first time I visited Mexico City, in the 1980s, it seemed endlessly hot and dusty. There was a water crisis and people were not allowed to wash their cars or sprinkle their yards. Looking at the arid land in the outskirts, I thought it must have always been that way. I asked my host, "Why would anybody build a city here?"

"This was a paradise on earth," he told me. "It took four centuries of Europeans' finest engineers to construct what we have now."

A Really Good Book

These blog posts are supposed to sound like genial messages from a friend while actually being advertisements for a commercial product (my book). Creepy, right? Hoping to cancel the whiff of bad faith, at least a little, I thought I would talk about other writers' books — stuff that I could tout with a clear conscience, because I get no benefit from it.

Many good books have been written about Jamestown — almost as many as about the Pilgrims. I was thoroughly impressed by Edward S. Morgan's American Slavery, American Freedom and Alan Taylor's American Colonies. But the book I most enjoyed was James Horn's A Land as God Made It, possibly because it had the closest focus on the people involved.

Many good books have been written about Jamestown — almost as many as about the Pilgrims. I was thoroughly impressed by Edward S. Morgan's American Slavery, American Freedom and Alan Taylor's American Colonies. But the book I most enjoyed was James Horn's A Land as God Made It, possibly because it had the closest focus on the people involved.

A passage that I underlined, as Jamestown leader Samuel Argall travels around Chesapeake Bay seeking some solution to the war against the Powhatan (the main local Indian power), which the English are losing:

It was the kidnapping of Pocahontas — [her father, Powhatan leader] Wahunsonacock's "delight and darling" — that proved to be the most important outcome of Argall's voyages. She happened to be staying with the Patawomecks in the spring of 1613 to "exchange some of her father's commodities for theirs" and visit friends. On hearing from some Indians that Pocahontas was in the area, Argall devised a plan to hold her hostage in return for English prisoners taken by the Powhatans in recent raids....Shortly after, [Argall's native ally] Iopassus and his wife enticed Pocahontas aboard the Englishman's ship and, after a "merry" supper, the Indians spent the night on board. The next morning, Iopassus and his wife were reward with a small copper kettle and "other les valuable toies" and left. Argall informed Pocahontas she would have to stay on board and return with him to Jamestown.