The truth is there are a lot of books I don't like, and even more books I have no interest in, but I made a decision a long time ago not to talk about those books, at least not in print. My opinions tend to be strong, and while I'm convinced that you should read the books I like, I'm not convinced you shouldn't read books I don't like. In 2005 I got to sit next to

John Updike at a luncheon at the American Academy of Arts and Letters. I was nervous and thrilled and wondering what in the world we were going to talk about. Based on that lunch and one subsequent meeting a few years later, I will say that John Updike was the loveliest guy in the world. We wound up talking about Jonathan Safran Foer's novel

Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, which I had loved and Updike had panned in the

New Yorker the week before. He asked me why I liked it, and then he told me all the things he had liked about it, and then he shrugged. "Maybe I was too hard on it," he said.

Updike? The New Yorker? "Maybe too hard"? At that moment I decided to keep my negative opinions out of print. Believe me, it's not that I think all reviews should be good reviews, but as someone who knows how hard it is to write a book, I would rather confine myself to praise.

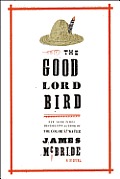

So let me tell you about The Good Lord Bird, a novel that I imagine has nothing but praise coming at it. At any given moment I probably have 20 books stacked up that I want to read or am supposed to read, and I try to keep them in some loose order. But every now and then a book comes along that breaks the line and jumps to the top of the stack. Such was the case with James McBride's The Good Lord Bird. When I read the front page review Baz Dreisinger had written for the NYTBR, I went straight to Parnassus and bought a copy, and then I went home and read it. I read it the way I used to read when I was a teenager: I read it while eating my cereal in the morning. I read it while walking from room to room. I read it well past the hour I was ready to go to sleep because I couldn't stop reading it. The book had electrified Dreisinger and that electricity was passed on to me, the newspaper reader. So even though I had no great interest in reading a novel about John Brown as told by a first-person narrator who is a child (with very few exceptions I avoid child narrators; they're not my thing), I felt compelled to read this book immediately.

From the first pages I knew it was like nothing else. There is tremendous immediacy in the voice, a snap and crackle of life that grabs you by the throat in much the same way John Brown grabs up everyone he meets. The lessons that our narrator — variously known as Henry, Henrietta, or "The Onion" — learns from Brown are ones he is slow to absorb, and I have to say I found myself thinking about this book for a long time after I had finished it, realizing it was still teaching me things that I was only just now coming to. I'd put my money on The Good Lord Bird to win big prizes.

From the first pages I knew it was like nothing else. There is tremendous immediacy in the voice, a snap and crackle of life that grabs you by the throat in much the same way John Brown grabs up everyone he meets. The lessons that our narrator — variously known as Henry, Henrietta, or "The Onion" — learns from Brown are ones he is slow to absorb, and I have to say I found myself thinking about this book for a long time after I had finished it, realizing it was still teaching me things that I was only just now coming to. I'd put my money on The Good Lord Bird to win big prizes.

And while we're on the subject of James McBride, you've read The Color of Water, right? It's one of those books I call a Universal Donor. Do you know someone who hasn't read a book in 10 years? They'll love The Color of Water. Know someone who reads everything? They'll love The Color of Water. If you know a child who's a precocious reader, or a child who hates to read, this is the book to give them. Want to pick a book that everyone in the book club or everyone in the city will love? Bingo: The Color of Water. The Good Lord Bird isn't quite as universal (only because it's more challenging), but truly, it's brilliant.

More from Ann Patchett on PowellsBooks.Blog: